The more one tries to understand the politics of Bihar, the more elusive it becomes—slipping away like sand through one’s fingers. A comman man in Bihar has a deep interest in politics. The crossroads, tea stalls and village courtyards of Bihar are always alive with discussions about national and global political affairs. In these spirited conversations, Biharis display a remarkable ability to present persuasive and imaginative arguments in defence of their preferred ideas or parties.

Torchbearers of Change

It is often said that every Bihari carries within him a born revolutionary temperament. To walk away from the conventional path is his natural instinct. A Bihari speaks his mind fearlessly on every aspect of life—whether it is a philosophical thought or a social issue, his words are clear, candid and assertive. In the socio-political sphere, it is widely believed that Biharis are torchbearers of change.

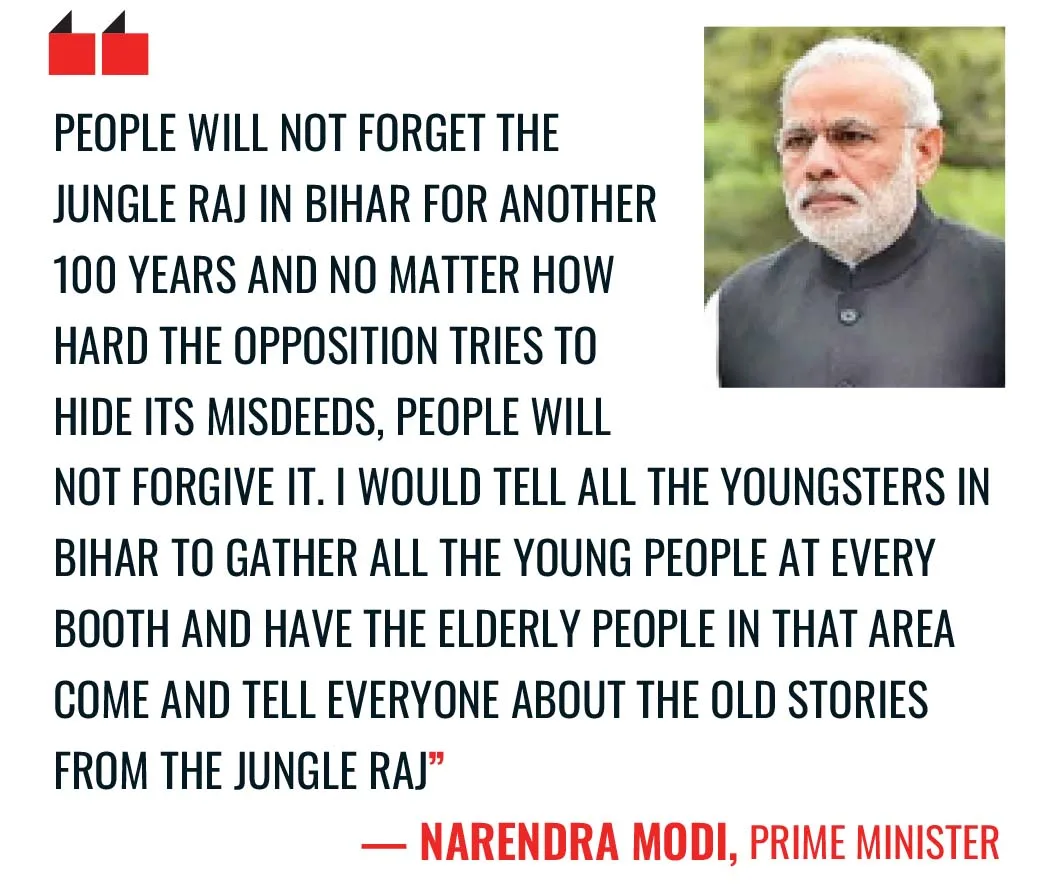

The same Bihar that once witnessed the splendour of Magadh, that was the sacred land of Buddha, Mahavira and Chanakya, gave India mighty rulers like Chandragupta. In ancient times, Bihar saw worldwide prestige of ancient universities such as Nalanda, Vikramshila and Odantapuri. Bihar also led the historic “Total Revolution” against the Emergency. However, Bihar was, in later years, fated to endure the darkness and crime of the Lantern Era. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the land which once symbolised the grandeur of ancient Indian civilisation later became the greatest victim of caste-based political experiments and their enduring curses in the post-Independence era.

Architect of Dark Era

Indian politics has often been more focused on personalities than ideologies. Bihar, too, has nurtured, celebrated and tested many political figures. Some of these personalities shone brightly—sometimes dazzlingly so, often accompanied by the glow of their families—but over time, Bihar gradually lost its own luster.

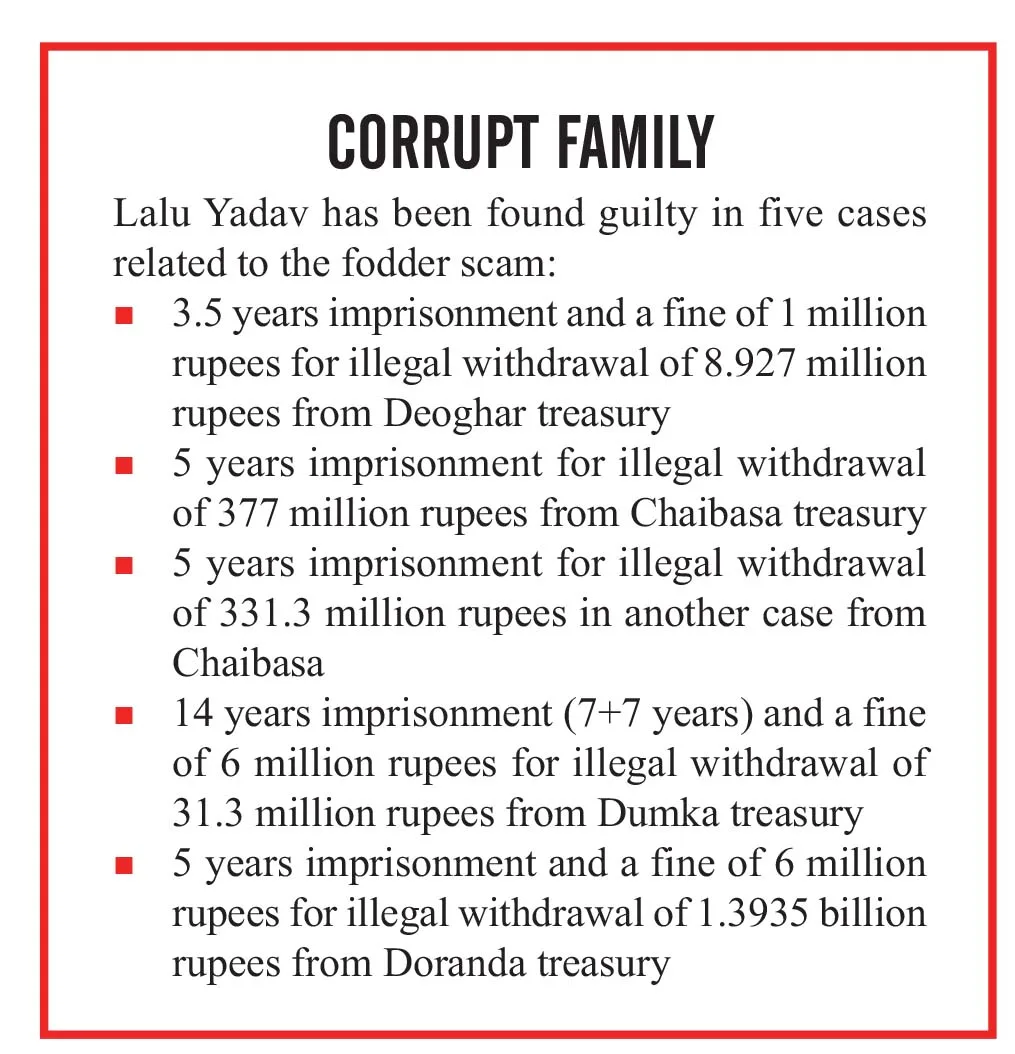

Among these figures, the most prominent was Lalu Prasad Yadav. Although Lalu’s spell may be fading today, there was a time when his influence captivated the masses. Emerging from the womb of the JP Movement, Bihar had pinned great hopes on him. Unfortunately, his socialism gradually transformed first into caste-based politics and then into family-centric politics. While he was seen by his supporters as a pioneer of social justice and a saviour of the poor, for his opponents Lalu Prasad Yadav became a symbol of political infamy and the architect of a dark era. Rarely has any other politician faced such intense support alongside equally intense opposition simultaneously.

Bihar, which was once known for its rich heritage, glorious past and pioneering intellectual tradition, saw a decline under Lalu Prasad Yadav. Through his rustic style, crude idioms and constant theatrics, he gave the State an unconventional and unrefined image. For those who took pride in Bihar’s cultural and intellectual legacy, this new image became a source of discomfort and shame.

Negative Impact of Lalu’s Reign

There came a time when, under this stigma, thousands of people who migrated from Bihar in search of livelihood began imitating the Delhi-Haryanvi style of Hindi, in a futile attempt to conceal their Bihari identity. In workplaces, people from Bihar were mocked and ridiculed by mimicking their accent. The pain and restlessness of seeing one’s identity reduced to an insult, and one’s mother tongue branded as a marker of backwardness, can only be truly understood by those who have endured it. The exploration of this self-serving, regionalist mentality — which deliberately fueled the campaign of neglect, derision, and humiliation against Biharis — is a discussion for another time. Yet today, it is crucial to ask: what were the direct and indirect consequences of the Lalu era? And what kind of psychological impact did it leave on the socio-political landscape of Bihar, both then and thereafter?

Bihar has long been known for its intellectual, literary and cultural vitality. Yet, there came a time when the seeds of caste-based hatred were deliberately sown, nurtured with care, and repeatedly harvested for political gain. During this period, the wheel of progress was turned backward. One could feel, almost palpably, that every town, village, or city was slipping further into decline with each passing year. Those familiar with Bihar would recall that during Lalu Prasad Yadav’s so-called era of “social justice,” people would lock themselves indoors soon after sunset. Shops would down their shutters as darkness approached. Any delay in returning home would cause visible anxiety on the faces of family members. Kidnapping had become a booming cottage industry, spreading from city to city, street to street. In those years, conversations at railway stations, bus stands, markets, offices, homes, and even universities revolved not around national or global issues, but around the exploits of some rising goon, strongman, gangster, or criminal. The most disturbing transformation was that the youth—boys growing into men—began to dream not of creating or contributing something noble or humane, but of becoming rangbaaz, bahubali, or gangsters themselves. The ultimate decline of a society is when it begins to see “heroism in its criminals.” Each caste had its own criminal “hero,” and communities began to rally behind their respective outlaws. The killing of a gangster belonging to a rival caste was celebrated almost as a “state festival”, while the death of one’s own caste-based criminal leader was mourned as a “national tragedy”. Consequently, the same Lalu who was once affectionately hailed as “Gudari ke Laal” gradually came to be seen less as a people’s leader and more as a domineering caste chieftain. To conceal his administrative failures, he resorted to divisive and incendiary slogans like “Bhura Baal Saaf Karo”—a thinly veiled call for hostility against castes such as Bhumihars, Rajputs, Brahmins, and Kayasthas. By nurturing this poisonous vine of hatred, he sought to preserve his hold on power through caste polarisation by any means possible. As a result, nearly every village and locality witnessed the rise of local Yadav strongmen whose influence, intimidation, and authority often surpassed that of the police and administration. In that dark age, the distinction between politician and criminal had all but disappeared.

Gradually, during the Lalu era, even State institutions began to undergo caste-based politicisation, and corruption was normalised under the guise of social justice. “Special collections” from people of other castes were glorified as acts of justice for the marginalised. These extortions occurred on almost every occasion — from purchasing land, cars, or houses, to opening shops or showrooms, and even during festivals, weddings, or family celebrations.

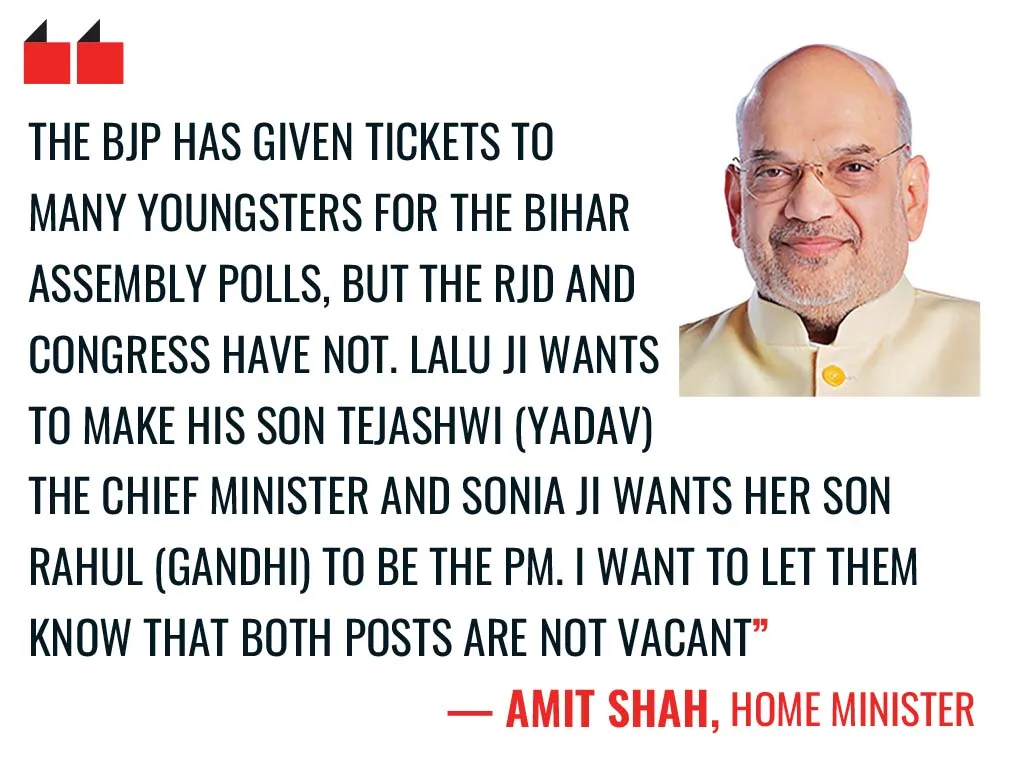

Adding fuel to the fire, the Leftist narrative of the time propagated the idea that those who possessed land or wealth were naturally deserving of being looted or dispossessed. Gradually, corruption and casteism became interchangeable terms, and their institutionalisation took firm root. Corruption evolved into a parallel, legitimised authority, while the so-called “messiah of the poor” and his caste-based loyalists transformed into a new, rising class of exploiters. The result was devastating. Industries and businesses began to shut down. Large traders and entrepreneurs fled the State. Talented and capable individuals migrated elsewhere. Those who remained were either small or marginal farmers, helpless laborers, or beneficiaries and collaborators of the corrupt system. In time, even the working-class population began migrating in large numbers from Bihar in search of livelihood — for the simple reason that the tambourine of caste identity cannot feed anyone; it neither gives bread nor employment. Eventually, disillusionment set in. Except for the Yadavs and Muslims (bound largely by their rigid anti-BJP stance), almost every other caste in Bihar became disenchanted with Lalu and his so-called brand of “social justice.” His vision of justice, once projected as inclusive, gradually narrowed down first to a single caste and community, and ultimately to his own family. Even within that family, differences of opinion, power struggles, and disputes over succession have continued to surface from time to time. His elder son, Tej Pratap Yadav, has already chosen a path of his own, while his daughter — though still within the party — occasionally raises dissenting voices from within.

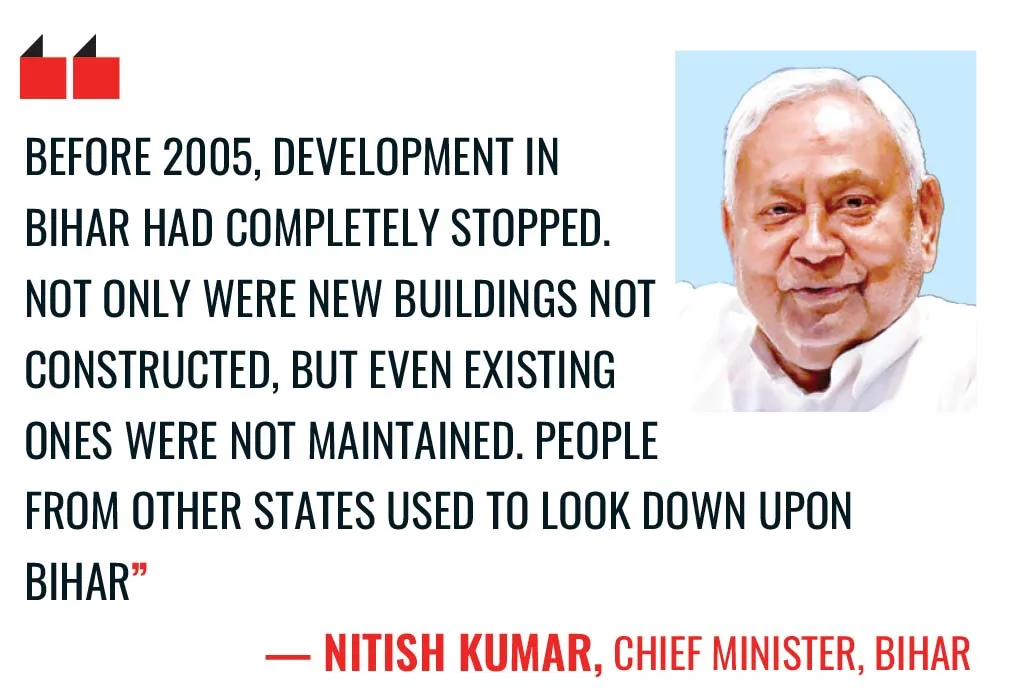

It is no surprise that, just as every era eventually comes to an end, the Lalu era too finally faded away. Just as a wooden pot cannot be placed on the fire again and again, casteism and appeasement politics cannot forever bring power. Even a master player like Lalu Yadav, known for his skill in caste polarisation and extreme appeasement, ultimately had to step down. The common people had grown weary of a government drenched in corruption. They longed for a clean administration and a crime-free Bihar. With the formation of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) Government under Nitish Kumar’s leadership in November 2005, a new chapter began in Bihar’s politics. Undoubtedly, his first tenure witnessed several positive developments — hope was rekindled, and public trust steadily grew. Organised and professional crime came under control. Kidnapping, which had grown like an industry, gradually became a thing of the past. The road and transport systems saw sweeping improvements. His second tenure was above average, while during the third, notable progress was made toward addressing basic issues like electricity, water and irrigation.

Most other political figures in Bihar remain confined to their own castes. For them, caste is merely a medium for power-sharing. Leaders like Upendra Kushwaha, Pappu Yadav, Jitan Ram Manjhi, Mukesh Sahani, and Pashupati Paras were never truly in a position to offer alternatives, and they still are not. Their influence is limited to swaying a small percentage of votes, which has further diminished in this election. Parties like the CPI (Maoist) or other communist groups may have some localised influence in certain constituencies, but they no longer possess any substantial grassroots base in Bihar. Following the end of the “Red terror,” their presence has dwindled to that of limping lizards. Most alliances formed among smaller parties are often more about post-election power deals than building solid and trustworthy political alternatives. Genuine efforts to create credible options remain rare.

It would not be unfair to say that no political party, no matter how frequently it comes to power, can bring about lasting change or development in Bihar without fundamentally reforming the style and culture of governance and administration. Corruption and casteism hollowed out Bihar like termites during the Lalu era, and to some extent, they continue to do so even today. Bihar demands comprehensive social, political and administrative reforms. Simply changing the government or the individual in power is unlikely to immediately transform Bihar’s future. If Bihar truly wishes to change its destiny, it must first dissolve the shackles of caste. It needs to emerge from caste-based rigidity and seek a political leadership that is liberal, visionary, sensitive, inclusive, and committed to development and good governance. Bihar must construct a society that is caste-free, healthy, vibrant, generous, cooperative, and inclusive. The education system must undergo radical transformation and attract substantial investment. Instead of a migration-driven economy, Bihar must build a self-reliant and autonomous structure that empowers its own people. Bihar’s Lalu-era past was dark and oppressive. It took the state not years but decades to recover from the bitter memories of that darkness. Bihar would not wish to return to the dense shadows of those memories. It is widely believed that Bihar has always been a pioneer in exploring new paths and nurturing progressive, forward-looking systems. The State has the ability to realise dreams and aspirations, and even amidst dense darkness, it has historically possessed the courage to advance steadily on the path of light. Today, Bihar is in an even stronger position than before. For political analysts, it will also be fascinating to observe whom Bihar chooses as the charioteer of its future, and why. One thing is certain: the outcome of the Bihar elections will play a crucial role in shaping the future direction of Indian politics.

Comments