The nation is preparing for a landmark celebration on October 31, 2025, to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Known rightly as the Iron Man of Bharat, he was Bharat’s first Deputy Prime Minister and the uncompromising force behind our nation’s territorial integrity. These large-scale, nationwide events will serve as a much-needed tribute to the colossal leader whose practical wisdom and resolute nationalism truly forged modern Bharat.

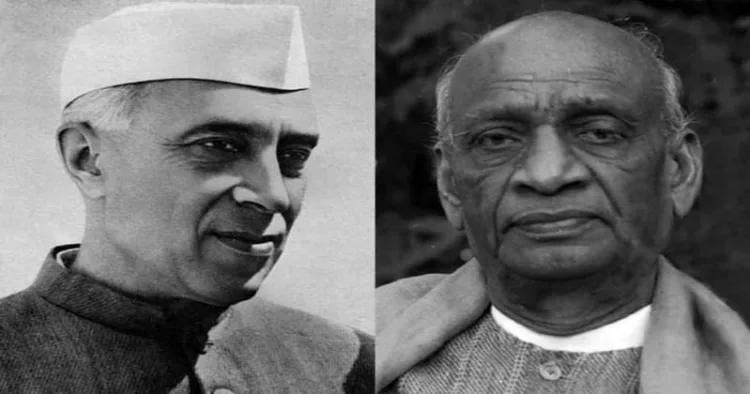

The early years of independent Bharat were shaped by a fundamental clash of ideologies and visions between two titanic leaders: Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru. This compilation of critical disputes exposes the profound differences in their approach to national security, foreign policy, and the very leadership of the Congress party, highlighting where Patel’s pragmatic nationalism was often sidelined by Nehru’s idealistic impulses.

The 1946 Congress Presidency: A sacrifice for ideology

The most pivotal and contentious disagreement occurred during the selection of the Congress President in 1946. This post was a clear stepping stone to becoming the first de facto Prime Minister of independent India. Despite 12 out of 15 Pradesh Congress Committees formally nominating Patel, Mahatma Gandhi publicly indicated his preference for Nehru. Demonstrating his profound respect for Gandhi and prioritising party unity over personal ambition, Sardar Patel stepped aside. This singular act effectively cleared the path for Nehru to assume the highest executive office, an outcome that allowed Nehru’s distinct ideological vision, rather than the majority will of the party, to dominate the newly formed government.

The Kashmir Crisis: Pragmatism vs. Idealism (October 26, 1947)

The immediate crisis following the accession of J&K starkly revealed their conflicting approaches to national security. After Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947, both men agreed to send troops, but tensions instantly surfaced over decisive action. When Mehr Chand Mahajan, the Prime Minister of J&K, urgently appealed for military deployment, an infuriated Nehru told him to “go away.” It was the firm, reassuring intervention of Patel that settled the matter and prevented a diplomatic disaster: “Of course, Mahajan, you are not going to Pakistan.” Patel strongly advocated for decisive action on the ground to solidify India’s position, but his advice was ignored when Nehru chose the path of international mediation, deciding to refer the issue to the UN. Patel’s pragmatic assessment, later encapsulated in his remark, “Kashmir is insoluble” (August 1950), proved tragically prescient.

The China Threat: National security warnings ignored (1950)

Perhaps the most catastrophic clash occurred over foreign policy and the emerging threat from Communist China. Following China’s invasion of Tibet in 1950, Sardar Patel recognised the geopolitical danger immediately. In a now-historic letter, Patel issued a serious warning to Nehru, expressing deep doubts about China’s peaceful intentions and urging the adoption of a tough, realistic stance. Patel saw China as a clear, immediate threat. In stark contrast, Nehru’s idealistic foreign policy and his belief in China as a “natural ally” led him to dismiss Patel’s well-founded anxieties as “unnecessary suspicion.” Nehru chose a policy of appeasement and idealism, tragically paving the way for future territorial conflicts by ignoring the national security imperative voiced by the Home Minister.

North-East Administration: Strategic neglect and its consequences (1950)

Sardar Patel’s grounded patriotism led him to strongly oppose Nehru’s fundamentally flawed policy of isolating the crucial Northeast region by placing its administration under the Ministry of External Affairs. Patel correctly diagnosed this move as strategically unsound, pointing out the adverse consequences of treating a domestic region as a foreign policy concern. Because of this administrative detachment, which no one in the cabinet dared oppose, the region’s connection to Bharat was weakened. The policy tragically made it simpler for external actors and Christian missionaries to propagate the narrative that local people were not Indians and that their country was distinct, thereby sowing the seeds of alienation in a sensitive border area. Patel’s warning, regrettably ignored, highlights his superior strategic foresight regarding national integration.

The Congress Party: Defending democracy and discipline (1950)

Sardar Patel fought consistently to ensure the Congress remained a disciplined, democratically structured organisation fit for building modern India. This commitment led to a direct organisational war with Nehru. The 1948 amendment, where Patel successfully banned dual membership and excluded the Nehru-aligned Congress Socialist Party (CSP), was a crucial move to ensure party coherence, a necessary check on ideological dispersion. The struggle peaked dramatically in the 1950 Congress Presidential election, a final test of strength. Nehru attempted to impose his will by unilaterally backing J.B. Kripalani against Patel’s candidate, Purushottam Das Tandon, even resorting to the threat of resignation if Tandon won. Tandon’s decisive victory (1,306 to 1,092 votes) was a clear mandate for Patel’s vision of discipline and democracy within the party structure, a victory Patel wryly acknowledged by asking Rajaji: “Have you brought Jawaharlal’s resignation?” This humorous yet pointed comment perfectly captured the high-stakes personal and ideological battle Patel had won.

Hyderabad: National security triumphs over idealism (September 17, 1948)

The integration of Hyderabad was a supreme test of nerve and strategic clarity, where Patel’s decisive will proved essential for national survival. As Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, Patel accurately recognised Hyderabad’s refusal to join India as an existential threat, famously and correctly diagnosing it as an “ulcer in the belly of India” -a threat compounded by the brutal Razakar militia. In sharp contrast, Nehru’s insistence on a prolonged, timid diplomatic approach, driven by excessive idealism and preoccupation with India’s international image or the possible intervention of the UN, unnecessarily risked national stability and delayed crucial action. It was Patel’s unwavering resolve that secured Bharat’s sovereignty by ordering Operation Polo, decisively integrating the state and demonstrating that internal stability cannot be sacrificed for external posturing.

Economic Policy: Resisting the socialist straightjacket (1947-1950)

Sardar Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru held drastically opposed views on the economic future of the nation. Nehru championed a socialist agenda, driven by the ideological desire for the ‘elimination of profit in society’ and the severe restriction of private enterprise. He looked to the Soviet model, replicating the Planning Commission and its Five Year Plans, ultimately pushing for a resolution for an economy on a ‘socialist pattern’ at the 1955 Avadi Congress session.

In stark contrast, Patel possessed a pragmatic, nation-building vision. He believed that capitalism could be “purged of its hideousness” and emphatically rejected the Marxist concept of class struggle. Crucially, Patel served as a vital bulwark against Nehru’s ideological overreach, being instrumental in purging Nehru’s initial calls for socialism from official Congress resolutions. In his minutes on the economic situation, Patel affirmed his faith in the nation’s capitalists, industrialists, and economists, recognising them as indispensable partners who, “when approached in the right manner,” offered promising prospects for both high production and fair labour remuneration. Patel’s realistic, market-oriented approach, unfortunately, yielded to Nehru’s restrictive, state-controlled socialist dogma.

Sardar Patel’s legacy is defined by his success in defending the fundamental structural integrity of Bharat against ideological missteps. He ensured the nation’s survival by crushing internal threats, upholding organisational discipline against Nehru’s attempts at personal party dominance (as seen in the 1950 Congress Presidential election), and battling the disastrous introduction of socialist economic models that restricted wealth creators. Though his sound warnings on the North-East and his pragmatic economic vision were often sidelined, Patel’s decisive actions secured the core stability of the nation. He stands as a towering example of a leader who chose nation-first realism over ideological purity, cementing an enduring blueprint for governance.

Comments