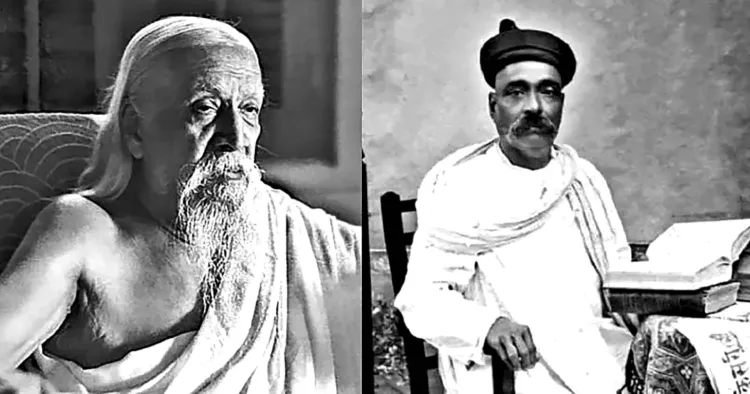

The Swadeshi movement that erupted in response to Lord Curzon’s Partition of Bengal in 1905 is conventionally understood through the lens of economic nationalism. Historians typically frame it as a strategic boycott of British goods coupled with the promotion of indigenous industries. But it was not just that. For Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Aurobindo Ghose, Swadeshi meant a comprehensive programme of sanskritik renaissance, spiritual awakening, and psychological warfare against colonial hegemony.

The Partition of Bengal served as the immediate catalyst, but the ideological foundations laid by Tilak and Aurobindo transformed what began as regional protest into a pan-Bharatiya movement for civilisational revival. Early responses to the partition followed predictable moderate patterns. The idea of boycotting British goods first appeared in Krishnakumar Mitra’s newspaper Sanjivani on July 3, 1905, and gained wider acceptance at the Calcutta Town Hall meeting of August 7, 1905.

This initial phase represented classic moderate methodology focused on constitutional agitation and economic pressure. The assumption was that demonstrating the economic costs of partition would compel British reconsideration. British goods were boycotted, and Swadeshi products promoted as patriotic alternatives. The movement’s early success in disrupting British commercial interests seemed to validate this approach.

However, Tilak and Aurobindo recognised that purely economic resistance, however effective in the short term, could not address the deeper sanskritik and psychological foundations of colonial domination. Their genius lay in expanding Swadeshi from tactical boycott into comprehensive programme for national regeneration that addressed what they saw as the root causes of Bharatiya subjugation.

Tilak’s revolutionary contribution to Bharatiya patriotism was in his systematic strategy for mass mobilisation. His transformation of the private Ganesh Chaturthi festival into a public celebration in 1893 represented a masterstroke of national engineering that connected tradition with political resistance. By introducing political songs and speeches into the religious proceedings, he transformed devotional gatherings into centers of anti-colonial consciousness.

Tilak’s newspapers Kesari and Mahratta became the intellectual foundation for this patriotism. His journalism connected contemporary politics with Hindu consciousness and traditional values. His articles were structured as dialogues with the people, providing both practical guidance for resistance activities and deeper philosophical justification for the national cause.

Tilak conceptualised Swadeshi not as economic strategy but as Dharma Yuddha – righteous war. This framing transformed boycott from mere tactical weapon into spiritual obligation. Every act of purchasing Swadeshi goods became an expression of dharmic duty, while using foreign products represented moral failure. This dimension gave the movement unprecedented power as participants understood that they are fulfilling sacred obligations rather than engaging in political tactics.

Tilak’s four-point programme of Swaraj, Swadeshi, Boycott, and National Education represented a comprehensive alternative to moderate constitutional methods. Swaraj was birthright, not privilege to be earned through good behaviour. Swadeshi expressed economic and sanskritik self-reliance. National education would create new generation of Bharatiyas proud of their heritage and capable of self-governance.

Aurobindo Ghose’s contribution to the ideological evolution of Swadeshi represented perhaps the most sophisticated theoretical framework for spiritual patriotism ever developed in the colonial context. His 1905 pamphlet Bhawani Mandir provided the philosophical foundation for understanding the nation as a living divinity. This conception revolutionised national discourse by connecting individual spiritual evolution with collective political liberation.

Aurobindo argued that Bharatiyas possessed knowledge, devotion, and heritage, but lacked the divine feminine power (Shakti) necessary to translate potential into achievement. Without Shakti, devotion remained passive. This analysis led him to a revolutionary understanding of the Swadeshi movement as vehicle for spiritual awakening rather than simply economic resistance. The nation demanded not merely political independence but spiritual regeneration of her children.

Aurobindo’s “Doctrine of Passive Resistance” articulated in 1907 extended this spiritual framework into practical politics. His approach aimed at complete non-cooperation with colonial system until full independence was achieved. Where European nationalisms typically emphasised shared language, territory, or political institutions, Aurobindo grounded Bharatiya patriotism in universal spiritual principles accessible to all humanity.

Tilak and Aurobindo recognised that colonial domination operated primarily through cultural hegemony that convinced Bharatiyas of their own inferiority and dependence on Western civilisation

This universalist framework allowed Aurobindo to present Bharatiya Independence as necessity for world progress rather than selfish regional demand. Independence thus became obligation to universal dharma.

Aurobindo’s emphasis on Shakti as key to national regeneration also provided sophisticated analysis of colonial psychology. British rule succeeded by convincing Bharatiyas of their own inadequacy and dependence. The cure lay not in adopting Western methods but in recovering indigenous sources of spiritual power that had sustained Bharatiya civilisation for millennia.

Tilak and Aurobindo recognised that colonial domination operated primarily through cultural hegemony that convinced Bharatiyas of their own inferiority and dependence on Western civilisation. Effective resistance required a comprehensive sanskritik renaissance that would restore confidence in own traditions while equipping for modern challenges.

The establishment of Swadeshi schools represented crucial battleground in this sanskritik warfare. The Bengal National College, founded with Aurobindo as principal, embodied new educational philosophy that combined reverence for Bharatiya heritage with practical skills necessary for contemporary life.

The Swadeshi movement pioneered by Tilak and Aurobindo represented far more than tactical response to the partition of Bengal. Their legacy challenges contemporary Indians to move beyond superficial adoption of Swadeshi symbols toward deeper engagement with the civilisational synthesis they envisioned. True Atmanirbhar Bharat requires not merely economic self-reliance but sanskritik confidence and spiritual maturity that can engage global modernity through indigenous wisdom traditions. Only by recovering this original Swadeshi vision can modern Bharat fulfill its potential as leading civilisation capable of contributing to universal human progress while remaining rooted in its own profound dharmic heritage.

Comments