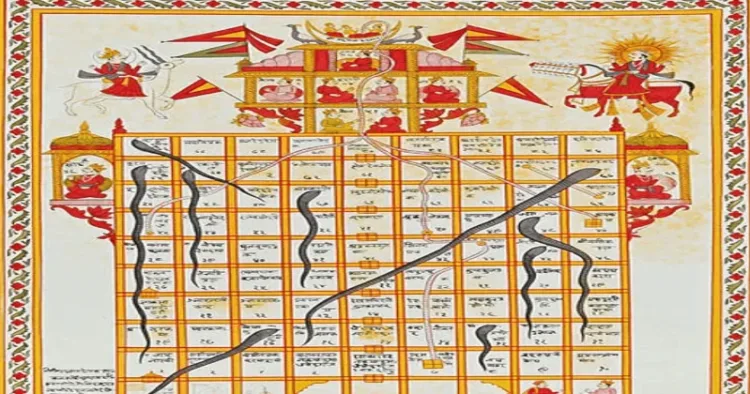

Long before the British renamed and repackaged it as Snakes and Ladders, India had a deeply philosophical board game known as Moksha Patam, a creation of the 13th-century sant and poet Gyandev. Far from being a mere pastime, it was originally designed as a spiritual and moral teaching tool for children that reflected India’s ancient wisdom and belief in karma, virtue, and the path to salvation.

In its earliest form, Moksha Patam was a symbolic journey of the soul toward moksha i.e., liberation from the cycle of birth and death. Each square on the board represented a moral lesson, a virtue, or a vice. It taught that one’s actions in life determine their progress or downfall. Ladders stood for virtues such as faith, generosity, and knowledge that elevated one toward enlightenment, while snakes symbolized vices such as greed, arrogance, and lust that pulled one down into misery.

A Game of Values, Not Chance

The Moksha Patam board contained 100 squares. Every ladder and snake carried a meaning tied to moral conduct. For instance, the 12th square stood for faith, the 51st for reliability, the 57th for generosity, and the 76th for knowledge. Climbing a ladder meant moral advancement which is moving closer to the 100th square, which represented Moksha or spiritual liberation.

In contrast, landing on squares associated with disobedience, arrogance, vulgarity, or theft brought one face-to-face with a snake. The 41st square represented disobedience, the 52nd theft, and the 99th lust, each leading the player downward, much like moral decay leads to spiritual regression in life.

The game’s final destination i.e. the 100th square symbolised Nirvana, or freedom from worldly cycles. The ladders often ended at squares depicting divine realms such as Kailash, Vaikunth, or Brahmalok, reinforcing that virtue leads one closer to the divine.

Colonial Appropriation and Cultural Dilution

When the British encountered Moksha Patam during their colonial rule in India, they recognized its popularity but stripped it of its profound spiritual and cultural roots. The game underwent major modifications when it was transported to England in the late 19th century and was renamed Snakes and Ladders.

In this Western adaptation, all elements of karma, morality, and spiritual growth were erased. The game was reduced to a child’s pastime focused solely on luck, a sharp contrast to the original, which linked every move to moral choices and their consequences. Even the number of snakes and ladders was altered, eliminating the deliberate imbalance that once reflected life’s moral challenges.

The British version diluted the essence of Indian philosophy, reshaping it to suit Victorian sensibilities. In the process, it lost its true purpose, a moral guide meant to show that good deeds uplift and elevate the soul, while bad deeds lead to downfall.

Historians view the transformation of Moksha Patam into Snakes and Ladders as one of many examples of how British colonialism diluted and rebranded India’s indigenous traditions. A game once rooted in moral and spiritual teaching was reduced to mere entertainment, reflecting how colonial influence often replaced India’s profound philosophies with simplified Western versions.

The game, which once taught lessons about karma (actions and results) and kama (desire), was turned into simple entertainment by the British. Its deeper message about destiny and moral choices, the heart of Sanatan philosophy was completely lost.

The true brilliance of Moksha Patam lay in its reflection of human life. Every move represented one’s journey through moral choices, where virtues led to progress and vices led to setbacks. It taught children that life was not governed by mere chance, but by one’s own actions and intentions.

Unlike other Indian games like Pachisi, which celebrated skill and luck, Moksha Patam highlighted moral destiny, that one’s path to liberation depended on righteous conduct. It was both a game and a spiritual guide, echoing the philosophy that life is a moral ladder, where every rise or fall depends on the choices one makes.

Today, as India works to revive and protect its cultural heritage, Moksha Patam stands as a reminder that even simple creations once carried deep wisdom and values. Understanding how this ancient game was altered is not just about looking back, it’s about reconnecting with the moral strength that once shaped Indian society.

The story of Moksha Patam and its transformation into Snakes and Ladders symbolizes more than just a lost game; it represents how colonial forces often repackaged Indian knowledge systems, erasing their spiritual essence to suit Western narratives.

To revive Moksha Patam and preserve India’s heritage, the Indian government can reintroduce it in schools to teach values, promote it through cultural campaigns, and support artisans to make traditional boards. Promoting the game through public awareness and tourism can show its true history, and international recognition can highlight its importance worldwide. These steps will keep Moksha Patam alive as a game that teaches values and India’s timeless wisdom.

Comments