“Our policy offers a red carpet to those who want to lay down arms… However, if someone takes up arms and kills innocent tribals, the State’s duty is to protect them and confront the perpetrators. I have no hesitation in using the phrase ‘ruthless strategy’, said Union Home Minister Amit Shah while reiterating that by March 31, 2026, Bharat will be completely free from Naxalism. It will be a historical occasion marking an end to one of the nation’s most prolonged internal security challenges. Shah emphasised that the Government’s dual strategy of sustained security operations and accelerated development has left Maoists weakened, their cadres surrendering in large numbers, and the so-called “liberated zones” slipping away from their grip.

Maoists have traditionally used the term “liberated zones” to describe territories under their control or strong influence. These areas used to form a central element of their strategy to establish a parallel administration and ultimately confront or challenge the State.

Amit Shah’s statement may sound too ambitious to those far from the forests of Chhattisgarh, but my own visit to Bastar, once a hotbed of Maoism, earlier this year gave me a glimpse of this transformation unfolding on the ground. What I saw on the ground convinced me that the Union Home Minister’s words are not mere rhetoric.

A Remarkable Transformation

Ten years ago, the image of Bastar was that of a cursed land – abandoned roads and villages, gunfire echoing through the jungles, security convoys blown apart, and people caught between Maoist and the State. When I returned, the landscape had changed. The same roads, once dreaded as death traps, now bore the steady movement of buses and trucks. Banks that had shut down, decades ago, have reopened. Schools that were once destroyed or shut down by Naxals are echoing again with the voices of children. It is not an overnight miracle – there are still scars, tensions, but the difference is real and undeniable.

Travelling through Sukma, I was struck by the words of my driver, Krishan Kumar Singh, a calm, sharp-eyed man who once drove senior officials through the most dangerous stretches of Bastar. He recalled how vehicles would change number plates multiple times to evade Maoist informers and how convoys were blown to bits just a few kilometres from where we drove. “Those days are gone,” he told me as we crossed a forested stretch once notorious for ambushes. “Now, even at night, you can travel without fear. Roads have improved, security has improved, and the Government is present in places where earlier no one dared to enter.”

Stories Of Redemption

In Badesatti village, which has been recently declared Naxal-free, I witnessed something that symbolised the quiet revolution in Bastar. Under the shade of a tree, a group of villagers were holding a Gram Sabha, discussing roads, healthcare, and jobs. Among them stood Vaneeta Sodhi, once a dreaded Maoist area committee member. For eighteen years, she lived in the jungles, participated in ambushes, and even admitted to being part of the 2007 Rani Bodli massacre, where more than fifty policemen were killed. Today, she speaks with regret but also with relief. “I used to come here to threaten these people,” she said, her eyes scanning the same villagers who now welcomed her presence. “Now I want to protect them. I never thought I would live to see such a day.”

Her transformation reflects precisely what the Union Home Minister highlighted – the reintegration of surrendered Maoists into democratic life. Vaneeta recently stood guard during Home Minister’s own visit to Bastar, a powerful image of how those once waging war against the State are now defending it. “The movement was a lie,” she admitted, urging her former comrades to surrender. “It destroys your body, mind and soul. Here, at least, you get a life of dignity.”

Infrastructure And Opportunities Return

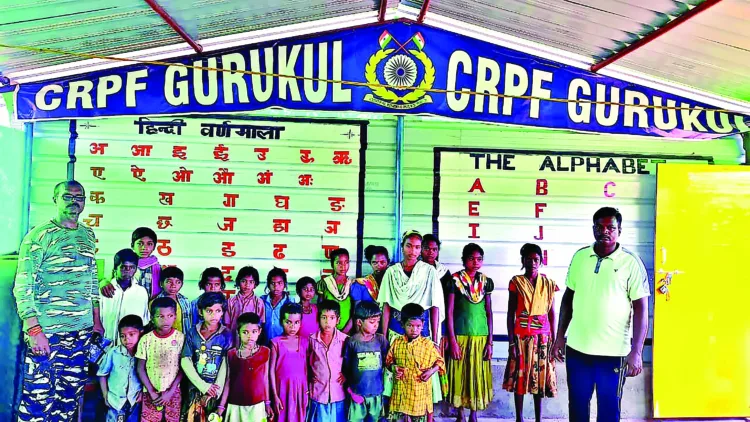

The change is visible not only in people’s testimonies but also in the infrastructure that is quietly reshaping Bastar. In Jagargunda, once Asia’s largest tamarind market, financial activities had come to a halt for over two decades after Maoists attacked the local Gramin Bank in 2001. On May 18 this year, a new branch of Indian Overseas Bank was inaugurated, bringing banking back to more than 14,000 villagers across 12 hamlets. For them, it was not just about opening accounts but about rejoining the mainstream economy. Local girls Tati Kamla and Parvati Nag are now employed as business correspondents at the bank. For them, working in a bank in Jagargunda would have been unimaginable until recently. The sense of normalcy is also returning in other ways. Villages like Puvarti, once strongholds of Maoists, now have bus services connecting them to Sukma. For decades, they remained cut off, accessible only through treacherous jungle routes. Now, young girls travel on buses, speaking about their dreams of becoming teachers, carrying schoolbooks instead of being forced into Maoist troupes. The CRPF Gurukul schools, set up in Maoist-hit villages, have reopened education to children who were once the first casualties of insurgency. I visited one of these schools, where charts and books filled a modest classroom, and saw the spark in children’s eyes – a spark that Maoist guns could never extinguish.

Perhaps the most striking transformation lies in the ranks of the District Reserve Guard (DRG), special units made up of local youth and surrendered Maoists. In Dantewada, I met Sundari Istam, who once fought with Maoist battalions and fired on police convoys. Today she wears the DRG uniform and serves alongside the very forces she once fought. “I used this gun to kill,” she told me candidly. “Now I use it to protect. Earlier, I had no salary, no identity. Now I have a home, land, and dignity.” Her story illustrates not only the futility of Maoist ideology but also the possibility of redemption when the State offers a second chance.

Signs Of A Naxal Free Future

The numbers back up these stories. From 126 districts under Maoist influence in 2014, the number has dropped to just about a dozen in 2025, mostly in Bastar and a few adjoining regions. Hundreds of Maoists have surrendered this year alone.

Yes, March 2026 is a deadline, but the reality on the ground shows that Bastar is steadily moving in that direction. From Gram Sabhas where people speak without fear, to surrendered Maoists guarding the same villages they once terrorised, to young girls proudly working, travelling on their bycycles and in buses, the signs are all around. Bastar is now truly liberating itself – from fear, red ideology, isolation and is proving to be the last bastion of Maoism, paving the way for real freedom and development.

Comments