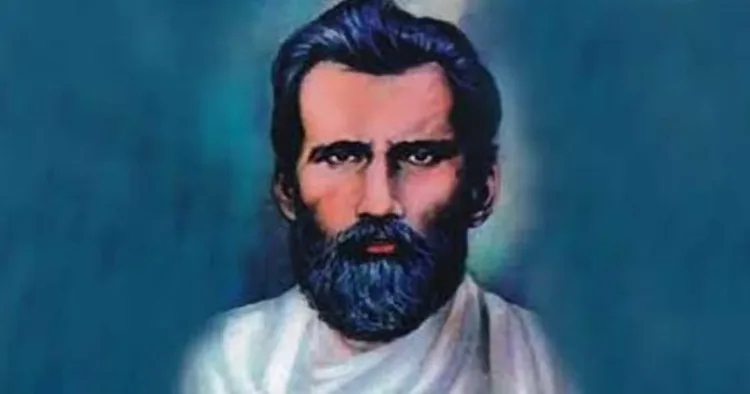

Known reverently as Utkal Mani or the Jewel of Odisha, Gopabandhu Das was more than a freedom fighter he was a poet, journalist, reformer, and the architect of Odia identity. Born on October 9, 1877, in the small village of Suando under Satyabadi police station in Puri district, Gopabandhu emerged as one of the foremost voices of social awakening and political consciousness in early 20th-century India. His life embodied sacrifice, simplicity, and service to the nation.

Orphaned of his mother soon after birth, young Gopabandhu grew up in adversity, but his trials only strengthened his resolve to serve others. He began his education in the village pathashala, showing an early flair for poetry and compassion for the suffering.

During his school years at Puri Zilla School, Gopabandhu came under the influence of M. Rama Chandra Das, whose selfless patriotism deeply inspired him. When cholera struck Puri during the famous Rath Yatra, Gopabandhu mobilised his friends to form the Puri Seva Samiti his first public service initiative. This spirit of community service would later define his life’s philosophy.

At Ravenshaw College, Gopabandhu’s moral strength and empathy were tested. When floods devastated parts of Odisha, he left home to help the victims even as his own son lay critically ill. His child passed away in his absence. Gopabandhu consoled himself by saying, “There are many to look after my son, but countless people cry for help. It is my duty to serve them; Lord Jagannath will take care of my boy.”

Tragedy struck again when, on the day he received news of his success in the Law Examination at Calcutta, he also learned of his wife’s death. Yet, his resilience never wavered.

He later practiced law in Puri and served as State Pleader of Mayurbhanj under the guidance of Madhusudan Das and the patronage of Maharaja Shri Rama Chandra Bhanja Deo. But legal success could not distract him from his higher mission to awaken his people through education and service.

Inspired by Gopal Krishna Gokhale’s Deccan Education Society, Gopabandhu founded the Satyabadi Bana Bidyalaya (School under the Trees) near Puri. It was not merely a school, but a laboratory of nationalism. Education was imparted in open air under the trees, where moral and civic virtues were nurtured alongside knowledge.

He was joined by a galaxy of intellectuals and reformers Pandit Nilakantha Das, Acharya Harihar Das, Pandit Godabarish Mishra, Pandit Krupasindhu Mishra, Pandit Basudev Mohapatra, and Ramachandra Rath collectively known as the “Satyabadi Panchasakha” (Five Friends of Satyabadi). Together, they infused the spirit of nationalism, secularism, and dignity of labour among students.

As a member of the Bihar and Orissa Legislative Council (1917–1920), Gopabandhu championed issues central to Odia identity unifying all Odia-speaking regions, preventing floods and famines, restoring the right to manufacture salt without excise, and spreading education.

At the 1919 Utkal Sammilani, where he served as President, Gopabandhu gave an inclusive definition of being an Odia: “Anyone who wishes well for Odisha is an Odia.” His resolution to align Utkal Sammilani’s goals with the Indian National Congress marked a turning point in the national movement in Odisha.

It was Gopabandhu who, at the 1920 Nagpur Congress session, proposed the creation of linguistic provinces a visionary idea that laid the foundation for India’s post-independence state reorganisation.

When Mahatma Gandhi launched the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1921, Gopabandhu led it in Odisha. His efforts brought Gandhi himself to the state to mobilise people. Arrested and imprisoned for two years, Gopabandhu continued his work from behind bars, inspiring thousands to join the freedom struggle. Subhas Chandra Bose aptly described him as “the father of the national movement in Orissa.”

In 1919, Gopabandhu Das founded the weekly newspaper Samaj, which became a daily in 1930. Through Samaj, he championed social reform, freedom, and Odia unity. The paper would go on to become one of Odisha’s most respected dailies, continuing his legacy of fearless journalism and advocacy for the common man.

On Lala Lajpat Rai’s invitation, Gopabandhu joined the Servants of the People Society (Lok Sevak Mandal), later becoming its Vice-President in 1928. His approach to service transcended caste, creed, and class. He fought against untouchability, supported widow remarriage, promoted women’s and vocational education, and urged people to balance rights with duties.

For Gopabandhu, the unity of language was integral to the unity of thought and civilisation. “Language is at the root of thought and civilisation. The unity of language ensures the unity of thought,” he once wrote a belief that continues to resonate in debates on cultural and linguistic identity today.

Gopabandhu Das passed away on June 17, 1928, but his ideals continue to guide Odisha and the nation. His name evokes the image of a man who lived for others an embodiment of sacrifice, intellect, and devotion to service.

Comments