In February 2025, a shocking case was reported at Bijainagar, a small town in Rajasthan’s Beawar district. Hindu teenage girls aged 13, 14 and 15 were targeted by Islamist gangs aiming to convert them to Islam for nikah post conversion. The accused systematically preyed on numerous girls, one after another, in this quiet town.

Blackmailing Their Victims

As of now, 14 suspects have been arrested in what is claimed to be an organised crime. Advocates fighting the perpetrators question the funding and motives behind the operation. The accused, all Muslims, targeted the girls, sexually exploited them, recorded the acts, and used blackmail and abuse to coerce them into luring more classmates into the scheme.

Similar Modus Operandi of Islamists

This case bears a striking resemblance to the infamous Ajmer blackmail and sex scandal of 1992, where Muslim youths trapped over 250 school girls, photographed them nude, raped them and blackmailed them. This high-profile case implicated prominent figures, from the Khadims of Ajmer Sharif Dargah to then Congress leaders, all complicit.

Thirty-two years later, after many victims had relocated, some had taken their lives, others changed identities, or aged, justice was partly served. In August 2024, an Ajmer court sentenced the remaining six accused in the case. A Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) court handed life imprisonment to those convicted in the sensational Ajmer sex scandal of the early 1990s.

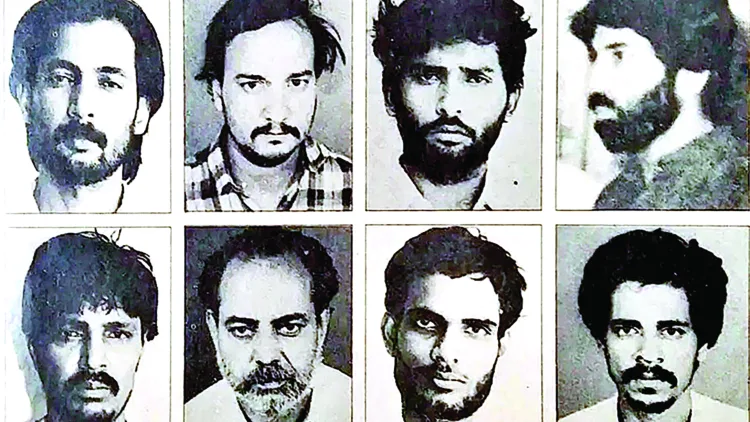

POCSO court judge Ranjan Singh imposed fines of Rs 5 lakh on each of the accused: Nafees Chishti, Naseem alias Tarzan, Salim Chishti, Iqbal Bhati, Sohail Gani, and Sayed Zameer Hussain, as confirmed by prosecution counsel Virendra Singh. Bhati was transported from Delhi to Ajmer in an ambulance for the trial. Of the 18 originally accused, these six faced a separate trial, while others had either served their sentences or been acquitted.

What Happened in Ajmer?

In Ajmer, a gang of Muslim youths orchestrated a chilling two-year scheme (1990-1992) targeting school and college girls, deceiving and raping them while using nude photographs for blackmail. The perpetrators, armed with film cameras, captured images processed at a colour lab, which they used to extort victims and coerce them into recruiting others.

Ajmer’s perpetrators, including influential Khadims and alleged Congress affiliates, sought personal gratification and power. Bijainagar’s case suggests religious conversion and caste-based targeting

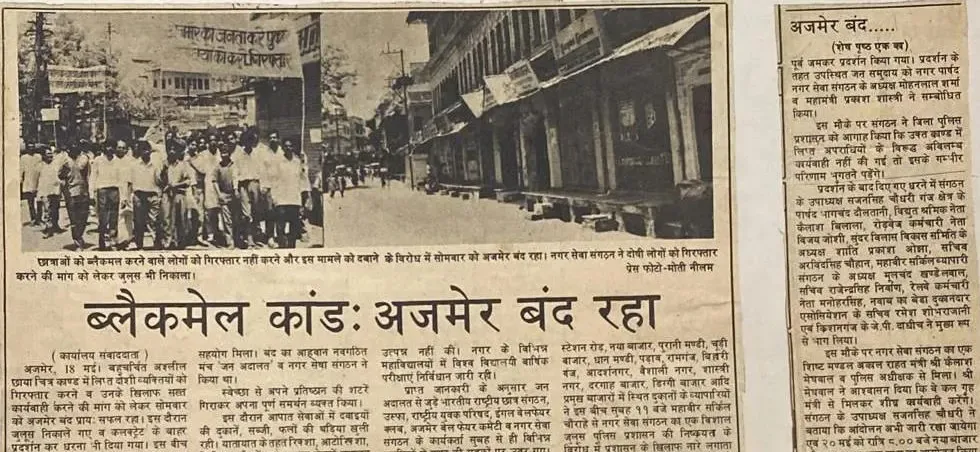

The scandal broke out on May 17, 1992, when Dainik Navjyoti journalist Santosh Gupta published a report with four incriminating photos. The exposé sparked outrage, leading to a citywide bandh on May 19 and a lawyers’ procession demanding arrests. A case (FIR 117/1992) was filed at Ganj police station, later transferred to the CID’s crime branch.

Investigations traced the operation to 1990, when Nafees and Farooque Chishti lured Deepak Chaudhary, son of a local shop owner, to a party at Saleem’s poultry farm in Hatundi. Drugged and photographed in compromising situations, Deepak was blackmailed for Rs 2,000 and coerced into introducing a girl, ‘A,’ an 11th-standard student with political ambitions. Nafees, exploiting her trust, raped her at Farooque’s farm in Faisagar, using threats and photos to silence her. The gang’s pattern repeated, targeting girls aged 17-20, including ‘B,’ ‘C,’ and ‘D,’ through deception, assaults at poultry farms, and relentless blackmail.

The accused, including Nafees, Farooque, Anwar Chishti, Ishrat Ali, Sohail Gani, and others, were linked to local businesses and the Ajmer dargah. Some, like Farooque, allegedly held various posts at Indian Youth Congress, though denied by party officials. Police faced scrutiny for initially releasing suspects and destroying evidence, possibly to avoid communal unrest. Chief Minister Bhairon Singh Shekhawat, accused of downplaying the case, insisted the CID was acting firmly.

On August 20, 2024, after 33 years, the court convicted several accused under IPC Sections 363, 366, 342, 376, and others, plus POCSO Act provisions. Of 18 original suspects, eight received life imprisonment in 1998, though four were later acquitted. One died by suicide, another remains absconding. The case, involving at least 16 documented victims (with estimates exceeding 250), exposed systemic delays and societal stigma.

Journalist Gupta, a prosecution witness, told Organiser, “A judgement is not justice.” Survivors, scarred by trauma and fear, continue to bear the burden of a protracted legal battle, underscoring the cost of delayed justice.

What Lawyer told Organiser?

In an exclusive interview with Organiser, advocate Virendra Singh Rathore detailed the horrific Ajmer 1992 sex scandal, where young Hindu girls were targeted by a gang, many linked to the Dargah’s khadim community. The accused befriended victims, raped them, and used obscene photos for blackmail, forcing them to lure friends into a growing web of exploitation. Promises of political positions, gas connections, or social status lured girls to secluded poultry farms or homes for filming.

Initially, 18 were accused; the first charge sheet was filed in 1992. Four were convicted in 1998, with sentences commuted by the Supreme Court in 2003 after 10 years served. In August 2024, six more received life imprisonment, all now behind bars. “This case spanned three generations of litigation,” Rathore said.

Ordeal Faced by Survivors

Survivors faced immense trauma, reliving their ordeal during repeated court appearances over 30 years. Many changed names, cities, or religions, hiding their pasts, some even from their husbands. Societal stigma silenced families, worsened by then DIG Omendra Bhardwaj’s claim that “no rape occurred.” Rathore criticised systemic failures: delayed FIRs, escaped accused, and the whistleblower Purushottam’s criminalisation, leading to his and his wife’s suicides. He called India’s judicial process “like climbing Mount Everest,” with no effective victim protection.

Rathore highlighted the case’s organised nature, noting some accused fled to Dubai, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, returning when scrutiny waned. While no direct Dargah involvement was proven, political and religious protection was evident. He warned of similar cases in Bhopal and Beawar, suggesting a pattern of targeted abuse of Hindu girls, possibly for conversion or humiliation, with some accused admitting to being paid. “This isn’t isolated,” he said. “Bharat keeps failing its daughters unless these crimes are recognised as organised assaults.”

Rathore stood firm: “Someone had to stand up. I did.”

Comparing Bijainagar Case to Ajmer 1992 Scandal

On February 16 and 17, 2025, media reports across Rajasthan and India highlighted a disturbing case in Bijainagar, where minor girl students were allegedly sexually exploited by Islamists. The details were harrowing, revealing a systematic scheme targeting vulnerable schoolgirls.

According to initial reports, families of three girls filed a collective complaint with the Vijay Nagar police, stating their daughters had been in contact with Muslim boys who provided them with distinctive Chinese-made mobile phones. These phones, compact and easy to conceal, were used to groom and exploit the girls. The victims, all friends from the same school, revealed they were coerced into recruiting other girls under threats of their nude photos or videos being leaked. Fear of social stigma kept them silent until their families intervened.

By February 17, the police had registered three FIRs (Numbers 60, 61, and 62/2025) and arrested seven suspects, including two minors. A press release from Vijay Nagar police confirmed, “Five accused, along with two minors, have been detained for trapping minor girls with Chinese phones for sexual exploitation.” The arrested individuals were Rehan (20), son of Jan Mohammad; Sohel Mansoori (19), son of Anwar; Lukman (20), son of Mohammad Usman; Arman Pathan (19), son of Kalu Khan; and Sahil Qureshi (19), son of Mohammad Sabir, alongside two unnamed minors.

On March 18, the Organiser team visited Bijainagar, where victims’ families submitted a memorandum at the police station, seeking protection from an accused individual, previously detained but released due to insufficient evidence. This individual was stalking schoolgirls preparing for Board exams, causing severe distress. One victim underperformed in her exam due to the accused loitering near her home.

Speaking anonymously to Organiser, families detailed the ordeals of four minor victims, all classmates at the same school:

Victim 1: Vivek (name changed), brother of two sisters (aged 13 and 14), uncovered their exploitation on February 15 after noticing missing shop money. One sister was caught using an unfamiliar Chinese phone with a SIM linked to Lukman Ali, who pressured her to meet near a graveyard, using abusive language. Lukman had stalked her, passed notes, and lured her with flattery to Chill Out Café and Pizza Hut, taking her on bike rides. The second sister was similarly targeted by another boy, using an identical phone. Both venues were later shuttered, with the café owner detained and encroachments cleared.

Victim 2: Suresh (name changed), a father, learned from Vivek that his daughter was sexually exploited. Introduced to the perpetrators by other girls, she was taken to cafés, forced to undress, photographed, kissed, and subjected to degrading acts, including slaps and abuse. Traumatised, she struggled to sleep and possessed a matching Chinese phone.

Victim 3: Shyam (name changed), a maternal uncle, reported his niece’s withdrawal and avoidance of social interactions. On February 14, she was restless to leave home but, after questioning, admitted her involvement with the gang, showing behavioural changes over months.

Victim 4: The fourth victim’s family, out of town during the visit, confirmed their daughter, a classmate, faced similar exploitation.

Police acted after the families’ complaints, but the case’s parallels to the 1992 Ajmer sex scandal, marked by blackmail and coercion, sparked widespread concern.

Parallels with the Ajmer 1992 Case

The Bijainagar case chillingly mirrors the 1992 Ajmer sex scandal, revealing persistent patterns of exploitation:

Similar Tactics: In both, girls from the same school were targeted, with victims coerced into luring others. Ajmer ensnared over 250 girls; Bijainagar exploited victims’ friendships. Ajmer used film cameras for blackmail photos, processed at a color lab, while Bijainagar’s perpetrators provided compact Chinese phones with registered SIMs for control and communication.

Control Mechanisms: Bijainagar’s accused tied black threads on victims’ hands and legs as a ritualistic control tactic, absent in Ajmer. In Ajmer, nude photos ensured silence; in Bijainagar, resisting girls faced verbal and physical abuse, including knife cuts on wrists with Kalma-like chants as “divine punishment.”

Journalist Gupta, a prosecution witness, told Organiser, “A judgement is not justice.” Survivors, scarred by trauma and fear, continue to bear the burden of a protracted legal battle, underscoring the cost of delayed justice

Deception: In Bijainagar, perpetrators posed as Hindus, using Hindu names and kalawa, revealing their Muslim identities post-exploitation. Ajmer’s accused leveraged social influence or promises like political positions without explicit identity deception.

Religious Motives: Bijainagar families reported the accused taught victims Islamic practices, Roza, Namaz, hijab, aiming for nikah during Ramzan, suggesting conversion intent. Ajmer’s targeting of Hindu girls raised similar concerns, though conversion wasn’t explicitly documented.

Exploiting Victims: Both targeted emotionally vulnerable girls. Bijainagar’s victims often came from unstable families, missing parents or living with relatives. Ajmer exploited girls’ naivety or ambitions. Adolescents in both cases were swayed by flattery or peer pressure, with Bijainagar girls boasting about attention and Ajmer victims lured by social outings.

Distinct Motives: Ajmer’s perpetrators, including influential Khadims and alleged Congress affiliates, sought personal gratification and power. Bijainagar’s case suggests religious conversion and caste-based targeting, with alleged bounties (Rs 20 lakh for Brahmin girls, Rs 15 lakh for OBC, Rs 10 lakh for SC/ST), hinting at organised networks.

Ajmer’s 1992 exposure led to convictions in 2024, but Bijainagar, 33 years later, shows unchanged vulnerabilities. Modern technology (phones vs. cameras) and religious coercion in Bijainagar highlight evolving predatory tactics. Both cases expose systemic failures—delayed justice, societal stigma, and inadequate protection for minors—underscoring the urgent need for reform.

Comments