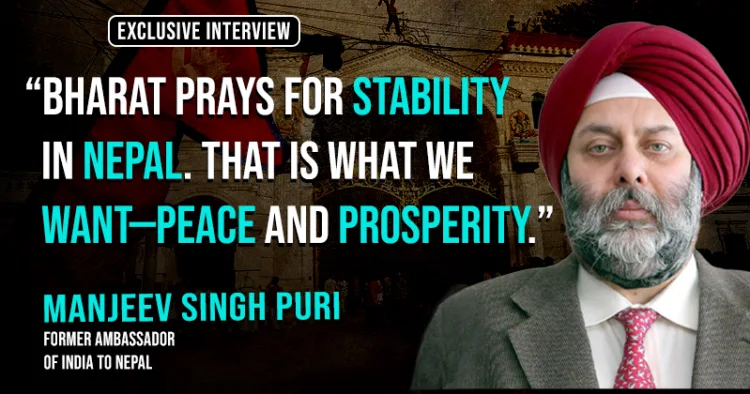

Amidst the fall of the Communist Government in Nepal, triggered by protests led by Gen Z, diplomacy in South Asia has once again taken a dramatic turn. Organiser Assistant Editor Ravi Mishra had an exclusive conversation with Manjeev Singh Puri, former Ambassador of India to Nepal. Excerpts.

Looking at the current scenario in Nepal, what led to the collapse of KP Sharma Oli’s government?

The immediate provocation was well known: the ban on social media. Why is social media so important in Nepal? Because nearly 20 percent of the population lives overseas. It is a society deeply exposed to globalization and heavily dependent on connectivity. This was crucial. The ban, therefore, created a pent-up sense of disenfranchisement. That said, there were deeper underlying factors like unemployment, an area where Nepal has hardly made progress. Most importantly, it was a government that had become completely unresponsive to the people’s needs and aspirations.

Thus, the social media ban became the thin edge of the wedge, driving people onto the streets. Unfortunately, this was accompanied by misuse of the people’s presence, violence by protestors, and a harsh retaliation by police and security forces. This escalated matters further, leading to a complete breakdown of law and order, weakening the Prime Minister’s position. In the political vacuum that followed, other leaders quickly moved in to fill the space.

Few experts argue that the protest escalated because of corruption issues. Do you think corruption was a factor?

Of course, without any doubt. People felt that the government was unresponsive, and what they witnessed was unchecked corruption leaders and their families indulging themselves while the public suffered.

It is deeply disturbing that riots have erupted in Nepal following similar unrest in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Why is this same pattern repeating across our neighbouring countries?

Globalisation and the spread of connectivity have transformed environments worldwide, and especially in our neighbourhood. Take Sri Lanka, which is perhaps the closest model for Nepal. What did people see? An economy in decline, heavy dependence on remittances and migration, and a government widely perceived as corrupt and unresponsive. The Rajapaksa government in Sri Lanka was seen as corrupt, indifferent to people’s needs, and presiding over a failing economy. With no alternatives left, people had no choice but to take to the streets.

In Nepal’s case, the government enjoyed a massive parliamentary majority and, as a result, became complacent and dismissive of public concerns. Bangladesh is somewhat different. There were several other issues at play—partly sectarian, with suggestions of external involvement as well. But still, these events across the region were closely watched by people in Nepal, who were not unaware of how others had risen against unresponsive regimes. One protest fed into another.

And that’s exactly what appears to me to have happened. In Nepal, the real breaking point was the government’s response: not just heavy-handed, but brutal. The killing of young people—over 20 shot dead—was something Nepal had not witnessed even during the monarchy’s fall. Such violence in the Kathmandu Valley was unprecedented and deeply wounded the people’s psyche. That is why calls for revenge and escalation followed.

Ultimately, the government had to accept that the writing was not just on the wall but written in bold letters. There was no way forward for them, and whether under pressure from the army or due to sheer political reality, they had to concede. This has created a political vacuum, which now awaits a new dispensation to fill.

The most interesting fact is that the government fell within two days. This looked like a systematic yet organic protest. Do you also believe there was any foreign hand involved, with funding from external forces?

I don’t believe so, not at all. Let’s understand this clearly. There was an organic element to the movement. That it was later used or misused by miscreants is a different matter. Nepalese society is very different from Bharat’s. Their exposure to globalization, their awareness of rights, and their connectivity to the outside world are on a much higher level—largely because 20 percent of the population lives overseas and the country depends heavily on remittances.

Moreover, after the Maoist insurgency, Nepal saw a proliferation of NGOs, church organisations, and other groups. This has changed the society’s mindset significantly, making it very different from our situation in Bharat. So, when the people reacted as they did, it was inevitable that miscreants and disruptive elements would take advantage of a genuine protest born of anger and frustration. That certainly happened. But the real failure was that the government did not respond in a manner expected of a responsible administration.

Any protest will attract disruptive characters who create trouble. The government should have been prepared and not reacted in such a heavy-handed way. In Nepal’s case, because of the nature of society and the country’s size—not very large but not too small either—the people’s anger spilled over rapidly. Within a day it spread across Kathmandu and beyond.

And yet, notice something remarkable: by the very next evening, as calls for restraint were made, Gen Z leaders were out in the streets cleaning and sweeping them. While a huge amount of property was damaged and government buildings were torched, there was hardly any loss of life except from police firing. Protestors even asked people to vacate government offices before setting them on fire. This is quite different from what we might expect elsewhere, and it reflects the unique nature of Nepalese society and protest culture.

How do you see the future of Nepal?

Look, Nepal is no stranger to political instability. But this is a unique and much deeper kind of instability. From the reports I saw until last night, there are efforts to bring Gen Z leaders into the process. The name of a former Chief Justice—someone with an impeccable reputation and a strong Nepali patriotic outlook—is being mentioned as a possible leader. With the army helping to midwife this process, there is hope that an interim government can be put together to set the ball rolling for a broader political process. Rebuilding, however, will take time and will come at a cost—there is no doubt about that.

How will it impact Bharat-Nepal relations?

I don’t think it will have much impact, and let me explain why. Our people-to-people ties with Nepal are extremely strong. For instance, one of the names being discussed as a possible leader studied in Banaras—this shows the depth of our connections. Bharat’s relationship with Nepal has always been rooted in its people, and we remain committed to that.

Bharat has consistently supported democracy in Nepal, and that has been a central element of our policy. Of course, there will be challenges and questions—was there some external hand, were monarchists involved, was Bharat encouraging them? Such speculation arises, and our media often amplifies it. But fundamentally, geography favours us in Nepal, and Nepalese leaders understand this reality. It will take some time for healing and calm to return. As has been rightly emphasised, even at the level of our Prime Minister, Bharat prays for stability in Nepal. That is what we want—peace and prosperity.

Comments