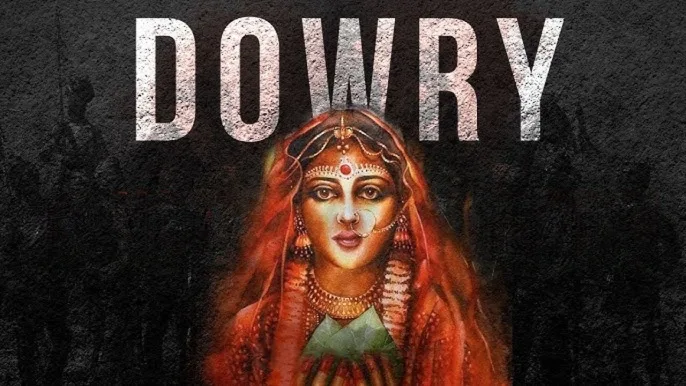

India is a land where women were once revered not only as mothers and nurturers, but also as sovereigns and warriors. From Rani Ahilya Bai of Malwa to Rani Abbakka, the first Tuluva Queen, our soil has given birth to women who shaped history and guarded Dharma. Against that backdrop, today’s headlines of dowry deaths sound not only tragic but shameful.

Take the recent case of Nikki Bhatti—a young bride who was burnt alive in front of her six-year-old child by her husband and in-laws. Her story is not an isolated crime; it is a blot on our collective conscience.

Despite our dream of being Vishwaguru—a beacon of spirituality and morality—such acts reveal how fragile our moral foundations still are. Over 70,000 dowry cases are reported every year in India, according to NCRB figures. Many end in brutal deaths. These numbers are not mere statistics; they are the silent cries of anguish. Behind each number lies a silenced story: a daughter who dreamed, a sister who loved, a mother who hoped. Nikki Bhatti’s case is not just her tragedy—it is a reminder that if it could happen to one daughter of Bharat, it could happen to any. And that truth should disturb us all.

When such horrors occur, critics seize the moment to question Sanātana Dharma itself: is this the culture you call sacred?

The honest answer is no. Dowry as we know it today is not Sanātana at all. It is a distortion to the principles of Sanatana Dharma. Our scriptures, and our cultural fabric were never built on practices that demeaned women, at the heart of Sanātana Dharma lies reverence for women. Far from sanctioning dowry demands, our scriptures recognized Strīdhana—a sacred wealth of her own, gifted to women to protect and empower them. The Manusmṛti eloquently defines Stridhan as :

“अयययावाहिनकं द ं च ीितकमिण । ातृमातृिपतृ ा ं षड् िवधं ीधनं मृतम्॥”

(Manusmṛti 9.194), translating to “Gifts given before the sacred fire, at the time of departure, tokens of affection, and gifts from brother, mother, and father—these six types are declared as Strīdhana.”

In other words, Strīdhana was hers—gold, ornaments, land, or money that remained under her control, untouchable even by her husband.

Alongside this was Śulka, or bride-price, where the groom’s side contributed wealth at the time of marriage. The practice of śulka—a contractual payment from groom to bride’s family—stands in stark contrast to today’s dowry demands, which invert the direction of wealth and burden the bride’s side. Both practices reinforced a simple principle: marriage should strengthen the bride, not impoverish her family.

The Vedas too envisioned the bride not as a dependent, but as a sovereign in her new home. The Atharvaveda (XI.5.18) blesses her:

सCाDी Eशुरे भव सCाDी Eèवां भव । नना%दLर सCाDी भव सCाDी अद्िह देवरान् ॥

“Be the empress over your father-in-law, be the empress over your mother-in-law. Be the empress over your husband’s sisters, and be the empress over his brothers.” This is the language of dignity, not subjugation. The bride entered her household not as a burden but as a queen.

This balance began to shatter under British colonial rule. The world often projects the West as a land of women’s liberation, but history tells another story: the feminist movement itself was born out of Western women’s long struggle against entrenched patriarchy. It is therefore no surprise that under British rule, women in Bharat too faced a systematic stripping away of rights they once held.

With the Permanent Settlement of 1793, land became locked into male hands, and women were systematically stripped of their inheritance and property rights. What was once Strīdhana—voluntary, protective wealth—was hollowed out. The colonial legal system ignored dharmic traditions, severed women’s property rights, and reduced them to dependents. In time, the safeguard meant for women twisted into an exploitative demand from them. As historian Veena Talwar Oldenburg argues in Dowry Murder: “The Imperial Origins of a Cultural Crime, it was colonial interference in property and inheritance laws that turned gifts into compulsory extractions. Dowry became a transaction of greed—an inversion of Dharma itself”.

Dowry violence is not just a crime under law. It is adharma. Our scriptures bless brides with long life, prosperity, and strength—not with the burden of satisfying greed. The Atharvaveda (XIV.2.64) prays:

शरदः शतम् हेम%तान् शतम् वस%तान् शतम् जीव शरदः शतम् ।

“May you live a hundred autumns, a hundred winters, a hundred springs; may a long life be granted to you.” This is the Sanātana vision—marriage as protection, not persecution.

Even today, some communities in India have stuck to their roots. Among the Khasi and Garo community of Meghalaya, property passes through women, and the youngest daughter becomes custodian of the family’s wealth. The Nairs of Kerala also followed marumakkathayam, a matrilineal system where men moved into the wife’s household. Many tribal communities of the Northeast are matrilocal, with men joining their wives’ families instead of the reverse. These living traditions remind us that dowry is not intrinsic to Indian culture. Rejecting it is not rebellion—it is continuity with our own heritage.

Dowry as practiced today is not Sanātana. It is a colonial-era corruption that warped a system meant to empower women. Reclaiming Strīdhana is not nostalgia—it is survival. It means creating a future where no woman fears marriage as a death sentence. Let us remember:

“?ीणां िह भषूणं धैय4म्।” —“Courage is the true ornament of women.”

And let us make a pledge together: our daughters will never be sold, our brides will never be burdened. That is the true Sanātana vow. If we act with courage and clarity, we can cleanse our society of this evil and return to a Dharma that honors, protects, and uplifts the women lineage.

Comments