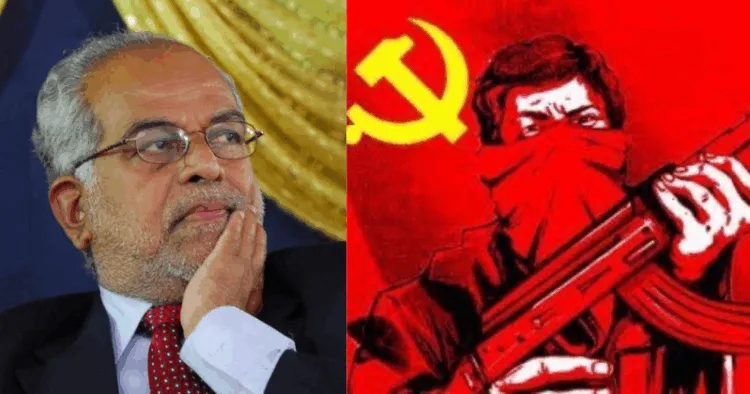

Once again, there is talk across the country about the victims of Maoist violence in Bastar. This time, the discussion has been sparked not by a new attack, but by politics — the Opposition’s decision to nominate retired Supreme Court judge Justice B. Sudarshan Reddy for Vice President.

For Delhi’s drawing rooms, Reddy’s name evokes a retired judge known for his lofty constitutional prose. In Bastar, it evokes something else entirely: the man who, on July 5, 2011, delivered the verdict that dismantled Salwa Judum, the tribal youth movement recruited by the state to fight Maoist insurgents.

The case — Nandini Sundar v. State of Chhattisgarh — declared Salwa Judum unlawful, banned the recruitment of tribals as Special Police Officers (SPOs), ordered that firearms be recalled, state funding withdrawn, and prosecutions launched. Three days later, Justice Reddy retired from the Court.

For thousands in Chhattisgarh who had lost family members to Maoist violence, the timing felt cruel. Many still believe that if that verdict had not been delivered, Maoist terrorism would by now have been history.

Coincidence, perhaps. But Justice Reddy’s story is filled with such coincidences. Too many, some would say.

The First Coincidence

Before joining the bench, Justice Reddy had been a practicing lawyer in the Andhra Pradesh High Court, often working with civil liberties advocate K. Balagopal. He appeared in more than 100 cases involving alleged security-force abuses against Maoists. That in itself was unremarkable. But when the Salwa Judum case came before him, Reddy leaned heavily on a 2008 Planning Commission report co-authored by none other than Balagopal.

Coincidence?

A Pattern of Familiar Names

Balagopal’s co-author on that report was Bela Bhatia, then a fellow at CSDS. It was that report which first framed Maoism as a “spontaneous tribal uprising” while calling Salwa Judum “state-sponsored terrorism.” That framing became the backbone of Reddy’s verdict.

Another coincidence

Among the expert group behind the report was economist Amit Bhaduri, who had popularized the term “developmental terrorism.” Reddy’s judgment cited him approvingly, giving his argument judicial legitimacy.

Yet another coincidence.

The judgment itself referenced the book The Dark Side of Globalization extensively, especially its sixth chapter. That chapter was written by a Delhi University professor who held the Ford Foundation Chair at Jamia Millia Islamia. The case was also closely associated with Delhi professor Nandini Sundar.

A series of academic names, repeatedly resurfacing in the judgment. Curious coincidences, piling up.

Ignoring the NHRC

During hearings, the Court asked the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to verify allegations against Salwa Judum. The NHRC’s report found over 90% of the claims false. It also noted multiple times that petitioners were wrongly conflating Salwa Judum with SPOs.

Reddy’s judgment chose to ignore this. Instead, it adopted the Planning Commission narrative, describing SPOs as “illiterate” or “Class V dropouts,” without noting that Maoists themselves had shut down schools to ensure tribals remained uneducated.

Another coincidence.

Old Affiliations, New Appointments

Justice Reddy admitted during hearings that he had once been an active member of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), an organization often aligned with civil liberties groups critical of counter-insurgency operations of security forces against Maoists.

After his judgment, further overlaps appeared. Balagopal, the key influence, had been appointed to the Planning Commission’s expert group by the UPA government. Soon after, that same government appointed Justice Reddy as Goa’s Lokayukta. Later, he served on a caste census committee in Telangana alongside Sukhdeo Thorat, another member of the expert group.

And today, he is the Opposition’s nominee for Vice President.

Coincidence after coincidence, until the pattern itself becomes the story.

Bastar After the Judgment

For Delhi, these may look like legal and academic debates. For Bastar, the consequences were real.

Once Judum was disbanded, its camps were dismantled, and villages were left exposed. Maoists swiftly reclaimed territory, burning homes, demolishing schools, destroying bridges, roads, and phone

towers. They imposed parallel rule through “people’s courts,” executing anyone accused of defying them.

Those who had sided with Judum were singled out. Families were wiped out. Mahendra Karma, the movement’s leader, was assassinated in 2013 in one of the bloodiest Maoist ambushes in history.

Petitioners continued filing cases against security camps. They did not visit the widows or the children left behind. For the tribals of Bastar, the wound never closed.

Beyond Coincidence

None of this proves conspiracy. Perhaps all of it was simply coincidence: the background of the judge, the experts cited, the ignored findings, the later appointments, the timing of his retirement. Coincidences that, one after another, reshaped Bastar’s fate.

But for those who lived through the fallout, coincidence is no comfort. Their shield against Maoists was taken away, and the violence that followed became their daily reality.

Today, the same judge is being elevated to one of the highest constitutional offices. For Delhi, it is an honour. For Bastar, it reopens an old wound.

The Vice Presidency is more than a ceremonial post. It signals what values the Republic chooses to honour. By elevating Justice Reddy, Parliament risks telling Bastar’s tribals that their pain was just another coincidence, to be footnoted and forgotten.

And that would be the cruellest coincidence of all.

The author blogs for AriseBharat

Comments