The tribal groups of India, with an oft-dependent view of their precarious situation, carry entire reservoirs of spiritual realisation, resilience, and harmony with nature. Not distant apart from the mainstream spiritual current of India, many tribal groups share this great, organic alignment with one of Hinduism’s most revered and esoteric gods: Bhagwan Krishna.

For them, Krishna is more than the gods; he is a friend, a teacher, someone to share joyful fighting and struggle, a wanderer of the forest. And so, the tribal people of India do something more than worship Krishna through forests, hills and rivers; they live Krishna in their life, their being.

The topic we will look at is how these tribal communities do resonate with Bhagwan Krishna, and internalize his teachings of embodying his spirit in their everyday life through encompassing forms – simplicity, struggle, detachment, and love for nature, and strong sense of dharma.

Krishna in the Forests: A Natural Relation

To understand why tribal communities resist connecting with Krishna we must first look back to the life of Krishna himself, and to the context within which he lived, and evolved. Krishna did not emerge from the womb of a gold child in a palace. Krishna did not grow up in grandiose infancy. His most rudimentary, basic life was with cowherders in the forest of Brindavan – among cattle, trees, rivers and music. He danced with the gopis in the moon, and he played the flute in the shadow of tamala trees, for hours on end, under the blanket of nature.

From this rustic and nature-embedded upbringing, we see parallels in the lives of many tribal groups. For instance, whether gauging the continuum of life of the Gond, Santhal, Baiga, or Bhil communities, their lives are aligned with the cycles of the earth. In the economy of the bansuri (flute), in the dance around the fire, in a deep respect for trees, animals, rivers; the people find Krishna as the eternal dweller in the forests.

While to the urban model of Krishna the argument can be made that he is a rich prince or statesman, tribes see Krishna the cowherd with animals at his side as the friend and helper of the weak and the marginalized. Perhaps in that sense, Krishna is one of them; as he walks barefoot enveloped in a world of earth smiling subtly through a difficult set of circumstances.

The Bhagavad Gita and its lessons for Tribal Life

While the Bhagavad Gita, as articulated by Krishna to Arjuna in the epic, may be regarded as a great philosophical text., In the context of tribal life, the concepts of: karma (duty), anasakti (non-attachment), shraddha (trust), and samatva (equanimity) do not appear to be lofty concepts. They are lived values.

1. Karma, without attachment

The phrase from the piece of literature ‘Karmanye vadhikaraste ma phaleshu kadachana’ (You have the right to perform your duty, but not to the harvest fruits), Krishna’s exhortation to Arjuna, is paraphrased less than in the daily life of a tribe. Tribal people engage with work soberly, whether it is through farming, hunting, gathering, or through different trades, but they do not put all of their intent into specific outcomes. The processes of production are not about ambition but purpose.

They plant seeds without any certainty of a harvest, but they do so with hope. They dance in the midst of lack. They take from the forest and give it the forest without attachment and without greed. This dignity of being resembles Krishna’s fundamental lesson in karma yoga.

2. Living with Attachments, Not With Disengagement

The Gita shows that detachment does not mean to think that we can renounce action, but to renounce the selfish attitude of ego, and possessive entitlement. Tribals have had a vast amount of calamity in their lives, but they do not live in a state of entitlement. The relation to their land – to life – is one of sacred stewardship rather than ownership. For them, forests are not “resources.” They are family.

So, while they may be facing displacement, or extreme poverty, they still may carry a deep sense of spiritual peace. This is not born of opposition, or dissent. This is gratitude that stems from an attitude of acceptance – a detached acceptance – just as Krishna tells us to practice with the wisdom of the Gita: “Samatvam yoga uchyate” (Equanimity is yoga).

The Soul’s Music: Tribal Culture and Krishna’s Joy

Although Krishna is known for a great many things, maybe nothing is more beloved than his joy—his music, his movements, his playfulness. This could be because tribal life, especially the harsh tribal life, is a life of feast and celebration. The tribal year, rituals, and daily life are filled with songs, dance, colors, and community celebration.

When tribals sing songs to the forest or dance in harvest celebrations, they in a sense recapitulate Krishna’s raas leela divine play. Remember when I said tribal art is never decoration? Think of it as the manifestation of spirituality. Through it’s creation it is a mode of uniting with the divine, to transcend to the divine- without temples or scripture.

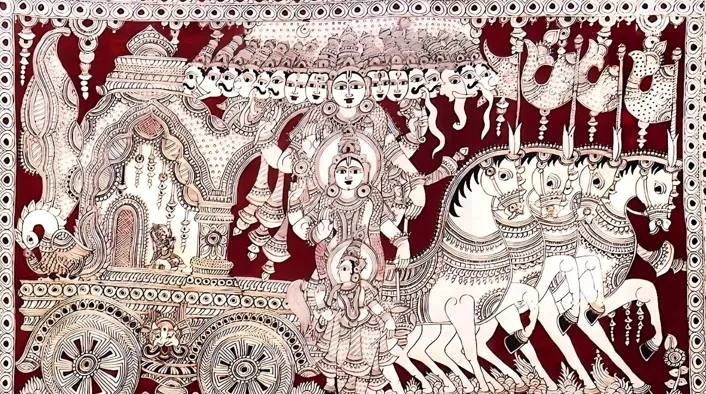

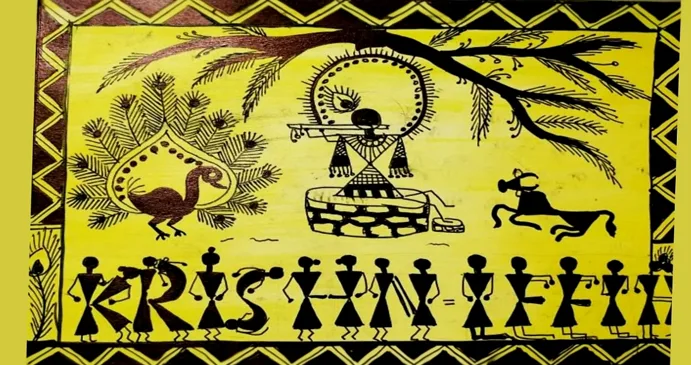

Many tribal communities, in fact, depict Krishna in their folk art. The Pithora paintings of the Bhil community, Warli art of Maharashtra, and Sohrai murals often include markings that mimic Krishna’s flute, peacock feather, or cowherding identity- subtle yet symbols that are not.

A struggle is a spiritual journey

Krishna never promised Arjuna an easy life, in fact, he told him to get up and fight, from a place of inner duty, not hatred. The tribals are intimately familiar with this struggle. The everyday struggle against poverty, the struggle against being placed in the periphery of society, the struggle for identity and their place in society, is embodied in the daily struggles that tribes face in a Krishna-like spirit of endurance, not bitterness and resentment.

Many tribal societies are often on the edge of modernity, like Arjuna on the battlefield, struggling with things like living a life of dignity vs living a life of survival; and like Krishna, they choose to endure towards either choice of action. They choose to turn struggle into poetry and resistance into resilience.

Even in instances of modernity won or lost, whether it be in something like keeping the forest whole, to keep their identity whole, to make their claim to rights as a way of reconciliation, the tribal voice is often a voice of strength through a non-violent and spiritual dharmic process, and not through anger.

Simple living, high thinking: The life of the yogi

Krishna describes the ideal yogi in the Gita someone who is grounded even when faced with chaos, has compassion for all beings, and lives harmoniously with nature shows us how the tribal way of life exemplifies this yogi life.

The lives of people living tribally are simple but not deprived. They are not excessive consumers, nor are they polluters. They have deep respect for their elders, honor women, protect animals, and have trees as ancestors. Their life is a practice of yoga where each movement is deliberate, respectful, and reverent. This is the way of Krishna. The yogi in the world, but not of the world.

Universal Krishna: The uncaged animal of martyrdom

Krishna was born in a jail cell, raised by cow herders, connected to both the low and the high; he never said he had to attach to a privilege or a hierarchy. His life occupied the world of social experience in a way that broke down boundaries. He shared food with Sudama, a poor Brahmin, and he danced with gopis without fear. His best friend was Balarama, a rural, all the same brand of strength, humility, and simplicity.

Tribal peoples see in Krishna a God who requires no hierarchy and loves all who love him. There is an endless number of regional legends claiming that Krishna walked through tribal villages, blessed their ancestors, or protected their woods. These oral traditions, passed down with reverence through generations, have become part of their living belief.

Krishna in Every Heart, Every Hut

As the world is modernizing at an incredible pace and as traditional wisdom is often ridiculed, it is worthwhile to remember what the tribal embrace of Krishna teaches us: spirituality is not about sophistication it is about sincerity.

Krishna, who walked among cowherds, who stole butter from children, who taught dharma on battlefields, who danced in moonlit forests is not bound to temples nor texts, he belongs to the everyday life of the simplest people.

Among India’s tribal communities this truth isn’t only taught it is lived. These lives are present yet hidden, and their relationship with Krishna is deep, beautiful, and long; is relationship with Krishna speaks of a God, who is not located within religious practice nor imposing wealth, but who smiles from behind trees, walks next to you in suffering, and sings through your soul.

While their struggle, silence, and song, the Tribals of India have become silent devotees of Krishna—not only through worship, but by being His message in motion.

Comments