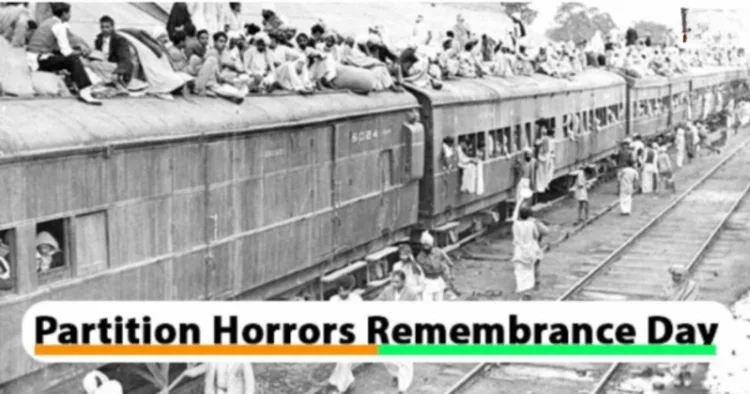

Every year, August 14 is marked as Partition Horrors Remembrance Day — a solemn occasion to reflect on one of the most painful ruptures in the subcontinent’s history. It is a day to mourn the millions uprooted, the countless lives lost, and the communities torn apart by decisions taken in drawing rooms far removed from the cries of the refugees. But remembrance without reflection is hollow. If we merely recount the tragedy without interrogating the political misjudgements that brought it about, we risk allowing these wounds to fester in silence. Partition was not just an inevitability shaped by communal tensions — it was also the result of hurried compromises, misread intentions, and an elite political leadership too eager to seal a deal with the British at any cost. The price of that haste was paid not only in 1947 but in every border clash, every refugee crisis, and every unresolved dispute that continues to haunt the subcontinent. Remembering Partition, therefore, must go hand in hand with revisiting the decisions that shaped it — and correcting the distortions that have seeped into the national memory. Only then can the observance of Partition Remembrance Day move beyond ritual, becoming an act of reclaiming our history and undoing the wrongs that still cast their shadow over India’s present and future.

India’s freedom was won under the banner of hope and sacrifice, yet beneath that triumph lies a troubling narrative of rushed compromise. Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, revered icons of the independence movement, were drawn into negotiations with the British that culminated in a blueprint for Partition. Their decisions—driven by wartime fatigue, political urgency, and misplaced trust—handed away long-term strategic control over borders, resources, and Kashmir. These negotiators of freedom inadvertently accepted a Faustian bargain, setting in motion consequences that India continues to grapple with today.

In the final months of British rule, the haste with which independence was pursued eclipsed sober consideration of nation-building imperatives. The Radcliffe Boundary Commission was granted only weeks to draw lines that would split provinces, sever communities, and channel mass displacement. Nehru, preoccupied with the larger goal of ending British rule, did little to challenge the timeline or demand more deliberation. As a result, Kashmir—a strategically vital and emotionally charged region—was initially left in limbo. Gandhi, whose moral vision shaped India’s independence narrative, spoke about unity until the very end. Yet, by failing to insist on delaying the Partition timeline, he allowed the hurried devolution of princely choices into British hands. In effect, control over the fate of Kashmir, with its complex political and demographic realities, slipped from India’s grasp before institutions were in place to manage it.

Moreover, in negotiating independence, Nehru and Gandhi underestimated how resource-rich districts and transport arteries were as crucial as political sovereignty. On one side of the border lay fertile agricultural belts, canal systems, and energy-rich territories. On the other, key railway links that would later define economic integration. The transfer of these assets was governed not by equitable logic but by hastily drawn lines. Gandhi’s philosophy merited moral integrity, but applied here, it yielded strategic vulnerability. Boundaries were not only mapping topography—they were mapping deprivation. Nehru’s focus on freedom from colonial rule overshadowed these physical realities, resulting in an economic fragmentation whose effects emerged gradually, but persistently.

In understanding these missteps, one can look to historian Ayesha Jalal’s piercing assessment: “India got freedom, but in losing Punjab and Bengal whole, it also lost key demographic and economic strength.” Though Jalal directs attention to the human cost of violent Partition, her words resonate equally with the strategic oversights of the negotiators. The vast agrarian heartlands that nourished emergent India had been bifurcated. The ports of Karachi and East Bengal, once integral nodes in the subcontinent’s trade network, tuned instead toward an independent Pakistan. That loss weakened India’s ability to rebuild quickly and to assert itself economically in South Asia’s new order.

Equally, Gandhi and Nehru ceded control of princely states to an onrush of events they failed to anticipate structurally. On paper, the accession of states like Kashmir, Junagadh, and Hyderabad was meant to follow a process—or at least a period of dialogue. In reality, the vacuum created by hastily withdrawn British authority meant these states fell under centrifugal pressures. In Kashmir, the vacuum allowed Pakistan to press an invasion before Nehru could establish a governing framework there. Gandhi’s idealism—a belief in moral persuasion and nonviolence—proved impotent in the face of freshly organized tribal raiding parties entering Srinagar. By the time Nehru did act, the state’s accession was locked into crisis. His much-quoted address to the United Nations painted India as the aggressed, but the initial failure lay in under preparedness, not diplomatic victimhood.

The economic fallout of these hurried negotiations was not limited to pastoral economies and princely states. Energy infrastructure, including hydropower projects and irrigation canals that spanned both sides of the new border, became contested. India lost unplanned access to water resources, severely affecting agricultural planning. The infrastructural projects that could have anchored early post-independence development faltered. Gandhi’s focus on village self-sufficiency and moral economy, and Nehru’s emphasis on iron and steel, did not translate into coordinated control of vital inputs such as water and power that had been disrupted by the Partition.

Yet, the heart of the failure lies in the political choices of Nehru and Gandhi—especially their unwillingness to delay independence to consolidate unity. Faced with British pressure and public expectation, Indian leaders were complicit in an accelerated timeline. Gandhi, although sceptical of Partition, eventually accepted it as an unavoidable compromise, calling it a “division that would pass away.” Nehru, with his vision of a unified, secular India, nonetheless conceded enough to race toward sovereignty. In grasping the intangible—freedom—they let go of the tangible—borders that held integrity, resources that empowered, and princely territories whose fates remained unsettled. These strategic loosening were not an act of visionary sacrifice—they were missteps, born of choice and convenience.

Compounding the tragedy is the persistent legacy of these decisions. The line drawn in 1947 remains disputed, contested in Kashmir, and militarized in Punjab and Bengal. Economic development in border regions remains sub-optimal because the foundations were broken in haste. Mistrust, triggered by these early mistakes, colours India’s relations with its neighbour and complicates regional unity. The Partition may be written into schoolbooks as the price of independence, but in reality, it was a decision to trade off long-term power for short-term milestone compliance.

In retrospect, India did achieve sovereignty—but only after losing the chance to enter independence fully prepared. Both , Nehru and Gandhi were heroes of liberation—but they were flawed architects of the transition. Their miscalculations—driven by haste, fear of communal collapse, and overreliance on moral persuasion—allowed critical regions like Kashmir to slip into ambiguity, resources to divide, and political autonomy to fracture. Freedom was real, but it came with a hidden price tag: an internally fractured sovereignty whose repercussions echo through generation after generation. If history is to serve as a teacher, then this episode demands more than mere commemoration—it requires a sober reassessment of how easily political ambitions and hurried compromises can undermine a nation’s future.

The British exit from India was neither a spontaneous retreat nor an act of magnanimity. It was a carefully calculated transfer of power designed to protect their strategic interests in the subcontinent and beyond. For them, 1947 was not about India’s freedom but about ensuring a friendly post-colonial arrangement where trade routes, military alliances, and economic dependencies remained intact. As historian Stanley Wolpert notes in Nehru: A Tryst with Destiny, “The British left in such haste that they left behind not a legacy of unity but of division, designed to serve their interests in a world no longer dominated by their empire.

Comments