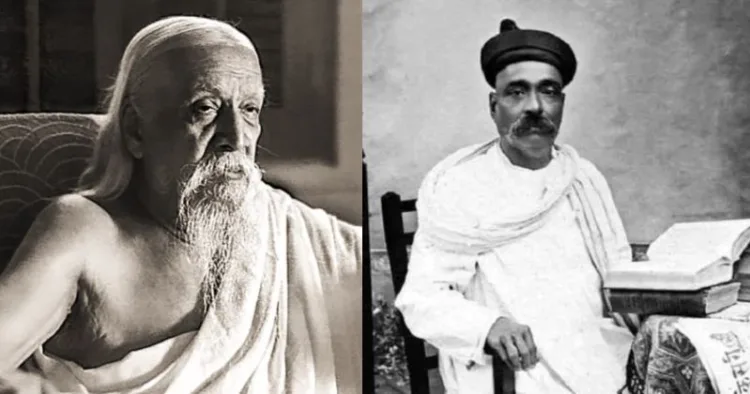

The Swadeshi movement that erupted in response to Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal in 1905 is conventionally understood through the lens of economic nationalism. Historians typically frame it as a strategic boycott of British goods coupled with the promotion of indigenous industries. This reading, while accurate in its immediate mechanics, fundamentally misses the profound civilizational transformation that Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Aurobindo Ghose envisioned through their interpretation of Swadeshi. For these towering figures of Indian nationalism, Swadeshi transcended mere economic calculation to become a comprehensive program of cultural renaissance, spiritual awakening, and psychological warfare against colonial hegemony.

The partition of Bengal served as the immediate catalyst, but the ideological foundations laid by Tilak and Aurobindo transformed what began as regional protest into a pan-Indian movement for civilizational revival. Where moderate Congress leaders saw Swadeshi as a tactical pressure point against British economic interests, these nationalist pioneers understood it as the essential foundation for a new Indian consciousness rooted in traditional dharmic values yet capable of confronting modern colonial challenges.

The conventional narrative of Swadeshi as economic boycott emerged from the immediate circumstances of the Bengal partition announced by Lord Curzon on July 20, 1905. The division of Bengal into Hindu-majority western Bengal and Muslim-majority eastern Bengal was ostensibly justified on administrative grounds, given the province’s population of nearly 80 million people. However, the true motive lay in weakening the nerve center of Indian nationalism that Bengal had become.

Early responses to the partition followed predictable moderate patterns. Leaders like Surendranath Banerjee organized petitions, public meetings, and press campaigns appealing to British sense of justice. The idea of boycotting British goods first appeared in Krishnakumar Mitra’s newspaper Sanjivani on July 3, 1905, and gained wider acceptance at the Calcutta Town Hall meeting of August 7, 1905. Rabindranath Tagore and others called for observing Raksha Bandhan on the partition day as a symbol of Bengali unity, while hartals and fasting marked October 16, 1905, as a day of mourning.

This initial phase represented classic moderate methodology focused on constitutional agitation and economic pressure. The assumption was that demonstrating the economic costs of partition would compel British reconsideration. British goods were boycotted, Rakhi bands distributed as symbols of unity, and Swadeshi products promoted as patriotic alternatives. The movement’s early success in disrupting British commercial interests seemed to validate this approach.

However, Tilak and Aurobindo recognized that purely economic resistance, however effective in the short term, could not address the deeper cultural and psychological foundations of colonial domination. Their genius lay in expanding Swadeshi from tactical

boycott into comprehensive program for national regeneration that addressed what they saw as the root causes of Indian subjugation.

Tilak’s revolutionary contribution to Indian nationalism lay not merely in his political methods but in his systematic cultural strategy for mass mobilization. His transformation of the private Ganapati festival into a public celebration in 1893 represented a masterstroke of nationalist engineering that connected religious tradition with political resistance. Prior to Tilak’s intervention, Ganesh Chaturthi remained largely a one-day private affair observed primarily by Brahmins and upper castes. Tilak recognized that religious festivals offered unique opportunities to bypass British restrictions on political assemblies while reaching masses untouched by elite constitutional politics.

The Ganapati festival under Tilak’s guidance became a comprehensive program of nationalist education. Large public images of Ganesha were installed in decorated pavilions, with each street collecting funds to support community celebrations. The innovation of unified immersion ceremonies on the tenth day created massive processions that served as displays of nationalist strength. More significantly, Tilak introduced political songs and speeches into the religious proceedings, transforming devotional gatherings into centers of anti-colonial consciousness.

The Shivaji festival, launched in 1896, served complementary purposes in Tilak’s cultural strategy. Where Ganapati celebrations fostered Hindu unity across caste lines, Shivaji commemorations specifically inspired Maharashtrian pride in resistance to foreign rule. The historical parallel between Shivaji’s struggle against Mughal empire and contemporary resistance to British rule was unmistakable. Young participants learned to see themselves as inheritors of a warrior tradition dedicated to Swaraj.

Tilak’s newspapers Kesari and Mahratta became the intellectual foundation for this cultural nationalism. Unlike moderate publications that focused on constitutional arguments and economic grievances, Tilak’s journalism connected contemporary politics with Hindu consciousness and traditional values. His articles were structured as dialogues with the people, providing both practical guidance for resistance activities and deeper philosophical justification for the nationalist cause.

Most crucially, Tilak conceptualized Swadeshi not as economic strategy but as Dharma Yuddha – righteous war. This framing transformed boycott from mere tactical weapon into spiritual obligation. Every act of purchasing Swadeshi goods became an expression of dharmic duty, while using foreign products represented moral failure. This religious dimension gave the movement unprecedented emotional power and staying capacity, as participants understood themselves to be fulfilling sacred obligations rather than engaging in political tactics.

Tilak’s four-point program of Swaraj, Swadeshi, Boycott, and National Education represented a comprehensive alternative to moderate constitutional methods. Where moderates sought concessions within the colonial system, Tilak demanded fundamental transformation of the

relationship between ruler and ruled. Swaraj was birthright, not privilege to be earned through good behavior. Swadeshi expressed economic and cultural self-reliance, not temporary pressure tactic. National education would create new generation of Indians proud of their heritage and capable of self-governance.

The psychological impact of Tilak’s strategy extended far beyond its immediate political effects. By grounding nationalism in Hindu religious consciousness, he created a framework for resistance that drew on India’s deepest cultural resources. Colonial authorities could suppress political meetings and ban seditious publications, but they could not prevent religious celebrations or control the messages embedded within traditional practices.

Aurobindo Ghose’s contribution to the ideological evolution of Swadeshi represented perhaps the most sophisticated theoretical framework for spiritual nationalism ever developed in the colonial context. His 1905 pamphlet Bhawani Mandir provided the philosophical foundation for understanding the nation not as political construct but as living divinity deserving total devotion. This conception revolutionized nationalist discourse by connecting individual spiritual evolution with collective political liberation.

The opening declaration of Bhawani Mandir – “WE IN INDIA FAIL IN ALL THINGS FOR WANT OF SHAKTI” – diagnosed the fundamental problem of Indian society as spiritual rather than merely political or economic. Aurobindo argued that Indians possessed knowledge, devotion, and cultural heritage, but lacked the divine feminine power (Shakti) necessary to translate potential into achievement. Without Shakti, knowledge became burden rather than weapon, devotion remained passive rather than transformative.

This analysis led Aurobindo to a revolutionary understanding of the Swadeshi movement as vehicle for spiritual awakening rather than simply economic resistance. Where conventional nationalism sought to transfer political power from foreign to indigenous hands, Aurobindo envisioned fundamental transformation of consciousness that would make Indians worthy of freedom. The nation, conceived as Bhavani Bharati or Mother India, demanded not merely political independence but spiritual regeneration of her children.

Aurobindo’s “Doctrine of Passive Resistance” articulated in 1907 extended this spiritual framework into practical politics. His program included organized boycott of British goods, officials, education, justice, and administration, backed by positive development of Swadeshi alternatives. However, unlike purely tactical resistance, Aurobindo’s approach aimed at complete non-cooperation with colonial system until full independence was achieved.

The spiritual dimension of Aurobindo’s nationalism distinguished it fundamentally from Western models of ethnic or civic nationalism. Where European nationalisms typically emphasized shared language, territory, or political institutions, Aurobindo grounded Indian nationalism in universal spiritual principles accessible to all humanity. India’s freedom struggle represented not narrow ethnic assertion but advance guard of human spiritual evolution.

This universalist framework allowed Aurobindo to present Indian independence as necessity for world progress rather than selfish regional demand. India’s spiritual heritage qualified her to lead humanity toward higher consciousness, but colonial subjugation prevented fulfillment of this global mission. Independence thus became obligation to universal dharma rather than mere ethnic self-determination.

Aurobindo’s emphasis on Shakti as key to national regeneration also provided sophisticated analysis of colonial psychology. British rule succeeded not merely through military superiority but by convincing Indians of their own inadequacy and dependence. The cure lay not in adopting Western methods but in recovering indigenous sources of spiritual power that had sustained Indian civilization for millennia.

The practical implications of this spiritual nationalism appeared in Aurobindo’s educational and cultural programs. As principal of Bengal National College, he implemented curriculum based on Indian traditions while incorporating modern knowledge necessary for contemporary challenges. Students learned to see themselves as inheritors of great civilizational tradition rather than recipients of colonial education designed to create subordinate administrators.

Aurobindo’s conception of boycott extended beyond economic realm to include what he termed educational, administrative, judicial, and social boycott. Each category represented systematic withdrawal from colonial institutions coupled with development of indigenous alternatives. This comprehensive non-cooperation aimed at rendering British rule practically impossible by denying it the Indian collaboration essential for colonial administration.

The Swadeshi movement’s most enduring contribution lay not in its immediate political achievements but in its systematic program of civilizational revival that created alternative framework for Indian identity. Tilak and Aurobindo recognized that colonial domination operated primarily through cultural hegemony that convinced Indians of their own inferiority and dependence on Western civilization. Effective resistance required not merely political organization but comprehensive cultural renaissance that would restore Indian confidence in their own traditions while equipping them for modern challenges.

The establishment of Swadeshi schools represented crucial battleground in this cultural warfare. The Bengal National College, founded with Aurobindo as principal, embodied new educational philosophy that combined reverence for Indian heritage with practical skills necessary for contemporary life. Unlike colonial education designed to create loyal subordinates, Swadeshi education aimed at producing confident inheritors of great civilizational tradition capable of independent thought and action.

The National Council of Education established in August 1906 systematised this alternative approach. Its stated goals included organizing literary, scientific, and technical education “on national lines and under national control” with vernacular languages as primary medium of instruction. This represented direct challenge to colonial educational policy that privileged English and Western knowledge while marginalizing indigenous traditions.

Traditional festivals and cultural practices were systematically revived and reinterpreted as vehicles for nationalist consciousness. Folk theater forms like jatras became platforms for disseminating Swadeshi messages to rural populations previously untouched by modern political ideas. Traditional songs were adapted to carry patriotic themes, creating popular culture that reinforced nationalist values through familiar aesthetic forms.

The revival of handloom production carried symbolic significance far beyond its economic impact. Every piece of Khadi or traditional textile represented assertion of Indian aesthetic values against colonial cultural dominance. The act of spinning and weaving became meditation on national identity, connecting contemporary resistance with ancient traditions of self-sufficiency and craftsmanship.

Swadeshi business enterprises, while often economically unsuccessful, served crucial psychological function by demonstrating Indian capacity for independent economic organization. The establishment of indigenous banks, insurance companies, soap factories, and textile mills challenged colonial narrative of Indian dependence on foreign expertise and capital. Even failed ventures contributed to growing confidence that Indians could manage their own economic affairs given political freedom.

The movement’s emphasis on traditional knowledge systems represented sophisticated challenge to colonial epistemology. Promotion of Ayurveda over Western medicine, indigenous crafts over machine production, and traditional education over colonial curriculum asserted validity of non-Western ways of knowing and being. This cultural resistance prepared ground for post-independence assertion of alternative modernity rooted in Indian civilizational values.

The psychological dimensions of the Swadeshi movement represented perhaps its most sophisticated contribution to anti-colonial resistance. Tilak and Aurobindo understood that colonial rule depended not merely on military force but on psychological acceptance of British superiority and Indian inadequacy. Effective resistance required systematic deconstruction of colonial cultural hegemony coupled with reconstruction of indigenous identity framework based on civilizational pride and spiritual confidence.

Handloom became central symbol in this psychological warfare because it embodied authentic Indian identity in opposition to machine-made foreign goods. Every act of wearing Khadi represented choice of indigenous over foreign values, traditional over modern methods, spiritual over material priorities. The sight of prominent leaders wearing simple handspun cloth challenged colonial associations of prestige with Western fashion and consumption patterns.

Traditional festivals transformed into sites of nationalist consciousness served dual function of cultural preservation and political mobilization. Participants simultaneously celebrated ancestral traditions and affirmed contemporary resistance to foreign rule. The integration of political messages into religious observances created seamless connection between

devotional practice and nationalist commitment that proved impossible for colonial authorities to suppress without appearing to attack Hindu religion itself.

The revival of Sanskrit learning and indigenous intellectual traditions challenged colonial monopoly on legitimate knowledge. Tilak’s scholarly works on Vedic astronomy and Aurobindo’s philosophical writings demonstrated Indian capacity for original thinking that equaled or surpassed Western achievements. This intellectual renaissance restored confidence in indigenous wisdom traditions while proving Indian ability to engage modern challenges through their own cultural resources.

Swadeshi literature, music, and art created alternative aesthetic framework that celebrated Indian themes and sensibilities over colonial preferences. Patriotic songs became vehicles for emotional education that connected personal devotion with national cause. Folk arts were revived and adapted to carry contemporary messages while preserving traditional forms and techniques.

The movement’s success in creating psychological transformation appeared in widespread adoption of nationalist symbols and practices across Indian society. The popularity of Vande Mataram as unofficial national anthem, the spread of Ganapati and Shivaji festivals beyond Maharashtra, and the general acceptance of Swadeshi as patriotic duty indicated fundamental shift in Indian self-perception from colonial subjects to potential citizens of independent nation.

The Swadeshi movement’s ultimate significance lay not in its immediate political achievements but in its creation of ideological framework that made Indian independence psychologically conceivable and culturally desirable. By the time the movement declined around 1908, it had fundamentally altered Indian political consciousness in ways that made future nationalist movements inevitable.

The contemporary resonance of Swadeshi principles in India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative demonstrates the enduring relevance of Tilak and Aurobindo’s civilizational approach to national development. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s emphasis on self-reliance explicitly acknowledges continuity with Swadeshi traditions, while Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh ideologues celebrate the movement as foundation for contemporary Hindu nationalist politics.

The parallel between early twentieth-century Swadeshi and twenty-first-century Atmanirbhar extends beyond superficial similarities in promoting indigenous production. Both movements understand economic self-reliance as essential foundation for cultural independence and national sovereignty. Both reject the colonial assumption that modernisation requires wholesale adoption of Western methods and values.

The Swadeshi movement pioneered by Tilak and Aurobindo represented far more than tactical response to the partition of Bengal. Their visionary expansion of Swadeshi from economic boycott into comprehensive program of civilizational revival created ideological foundation for modern Indian nationalism while pointing toward possibilities for indigenous modernity rooted in traditional wisdom yet capable of engaging contemporary challenges. Their genius lay in recognizing that genuine independence required not merely transfer of political power but fundamental transformation of consciousness that would make Indians worthy inheritors of their great civilizational heritage.

The movement’s emphasis on cultural symbols, festivals, education, and psychological warfare against colonial hegemony established templates for resistance that continue to influence Indian political discourse. By grounding nationalism in dharmic principles while maintaining universal spiritual vision, Tilak and Aurobindo created framework for national development that transcended narrow ethnic or economic considerations to embrace comprehensive human flourishing.

Their legacy challenges contemporary Indians to move beyond superficial adoption of Swadeshi symbols toward deeper engagement with the civilizational synthesis they envisioned. True Atmanirbhar Bharat requires not merely economic self-reliance but cultural confidence and spiritual maturity that can engage global modernity through indigenous wisdom traditions. Only by recovering this original Swadeshi vision can modern India fulfill its potential as leading civilization capable of contributing to universal human progress while remaining rooted in its own profound dharmic heritage.

Comments