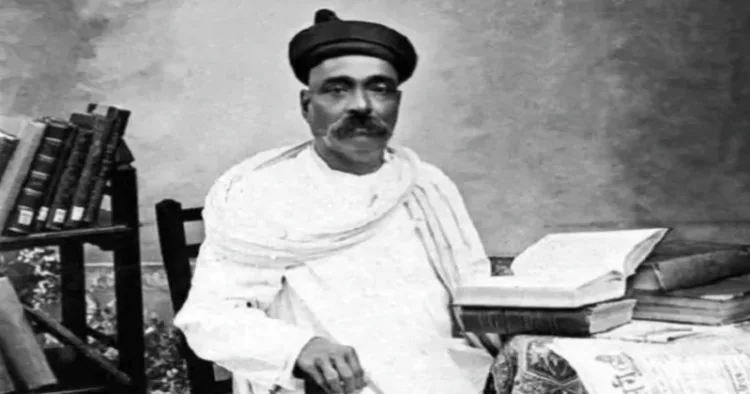

Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak was one of the foremost architects of India’s early nationalist movement, remembered not only for his fiery call for Swaraj but also for awakening the collective political consciousness of a colonised nation. Born in 1856 in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, Tilak was a scholar, journalist, teacher, and political thinker who refused to accept British rule as a permanent condition. He was among the first leaders to assert unequivocally that India’s freedom was not a matter of negotiation but a right that must be claimed through struggle. Tilak’s contribution to India’s freedom struggle lies in the ideological foundations he laid for assertive nationalism, in his use of cultural revival as political resistance, and his organisational brilliance, especially through the establishment of the Home Rule League. His life and work inspired a generation of Indians to see British colonialism not as a distant or benign administration but as an active force of oppression that needed to be resisted with courage, intellect, and unity.

One of Tilak’s earliest and most influential contributions was his pioneering use of journalism to challenge British imperialism. Through his newspapers, Kesari in Marathi and The Mahratta in English, Tilak wrote scathing editorials criticising British policies, exposing the economic drain of India’s resources, and advocating for self-rule. His writing was sharp, persuasive, and grounded in deep historical and political understanding. Unlike moderate voices of the time, Tilak did not appeal to British conscience; instead, he addressed the Indian masses directly, urging them to awaken to their political rights and cultural heritage. His newspapers became tools of political education for thousands, creating a shared vocabulary of resistance that reached beyond the elite to the common people.

Tilak’s genius also lay in his ability to connect political resistance with cultural identity. At a time when the British sought to portray Indian civilisation as backwards and unworthy of self-governance, Tilak promoted cultural pride as a foundation for political action. He popularised public celebrations of Ganesh Chaturthi and Shivaji Jayanti, transforming them from local religious or historical observances into powerful public events that unified people across caste and class lines. These festivals, while rooted in tradition, became arenas of political mobilisation where nationalist songs, speeches, and performances fostered a sense of collective identity. In doing so, Tilak subtly redefined nationalism, not just as a political aspiration but as a civilisational awakening. This was a radical departure from Western liberal models of resistance and marked a uniquely Indian approach to anti-colonial politics.

A fierce critic of colonial economic policies, Tilak was among the first to analyse and expose the structural exploitation underlying British rule. He wrote extensively on how British taxation, land revenue systems, and the destruction of indigenous industries had impoverished India. His advocacy during famines, particularly the Deccan famine of 1896–97, was especially notable. He not only provided relief but also held the colonial government morally accountable for its negligence. His open criticism led to prosecution and imprisonment, yet his popularity only grew. When Tilak declared, “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it,” it was more than a slogan—it was a bold rejection of imperial authority and a call to arms for a subjugated people.

Tilak’s political activism was not confined to rhetoric or symbolic gestures. He was a strategist who believed in building lasting political institutions and grassroots support. His most significant organisational contribution came in 1916 when he founded the Home Rule League. The League aimed to demand self-government within the British Empire and was modelled partly on the Irish Home Rule Movement. Tilak’s version, however, had a distinctly Indian character. He understood that to create political pressure, the movement had to move beyond petitions and resolutions to a sustained campaign of mass education and mobilisation. The Home Rule League quickly established branches across Maharashtra, Karnataka, Central Provinces, and parts of North India. It held public meetings, published pamphlets in regional languages, and trained local activists in political work. This decentralisation was critical to its success and marked a shift from elite-centric politics to mass-based mobilisation.

The achievements of the Home Rule League were significant despite the colonial repression it faced. It played a pivotal role in spreading the idea of Swaraj as a tangible and immediate goal rather than a distant dream. It brought political discourse to towns and villages, drawing in farmers, teachers, shopkeepers, and women into active participation. It created an organised platform for future resistance and laid the foundation for the spread of nationalist ideas in vernacular languages. Importantly, the League proved that the Indian people were capable of organising, debating, and demanding political rights on their terms. It eroded the myth that only the British could govern, replacing it with a confidence in indigenous leadership and self-determination.

Tilak’s leadership during this phase was marked by pragmatism and vision. He recognised the need for political alliances and negotiations even as he remained committed to firm resistance. He understood that building a free India required both ideological clarity and organisational discipline. His style of politics combined oratory, scholarship, and public action in a way that made him immensely popular across regions and communities. His appeal extended far beyond Maharashtra; he was respected and admired in Bengal, Punjab, and the south, where his speeches and writings were widely circulated and translated. His stature as a national leader came not from official positions or privileges but from the force of his ideas and the depth of his commitment.

Tilak’s legacy is also evident in the manner in which he politicised education. He strongly believed that an awakened citizenry was essential for national regeneration. He established schools and supported the use of Indian languages as mediums of instruction. For Tilak, education was not merely a means of upward mobility but a revolutionary tool to break the chains of colonial subjugation. He encouraged critical thinking, moral courage, and a sense of duty toward the nation. His educational philosophy was deeply nationalistic yet inclusive, aiming to empower the masses and prepare them for responsible self-governance.

Even during his imprisonment, Tilak remained intellectually active. His most famous work, Gita Rahasya, written during his incarceration in Mandalay, reflected his deep engagement with Indian philosophy and its relevance to modern political life. In this text, he interpreted the Bhagavad Gita as a call to action rather than renunciation, aligning spiritual duty with political struggle. This was a profound philosophical assertion that duty to the nation was part of one’s dharma, thereby fusing metaphysical thought with practical politics.

Tilak passed away in 1920, just as India was entering a new phase of its struggle. Yet his impact did not end with his death. The ideological and organisational structures he helped build continued to influence subsequent movements and leaders. His emphasis on mass mobilisation, cultural pride, economic critique, and fearless journalism provided a blueprint for resistance that many would follow. He redefined what it meant to be an Indian nationalist at a time when loyalty to the British Crown was still considered respectable by many.

Tilak inspired millions not to seek favour but to seek freedom, not to beg for reforms but to demand rights. His life was a reminder that India’s liberation would not come from the benevolence of rulers but from the awakened will of its people. In this sense, Lokmanya Tilak remains not just a figure of history but a symbol of the eternal quest for self-respect, justice, and national dignity.

Comments