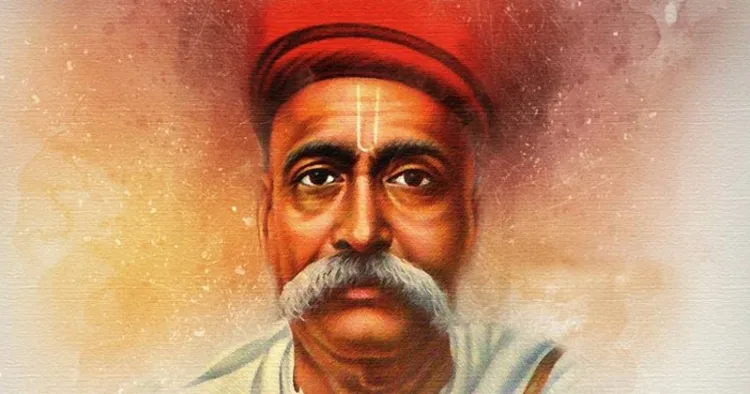

On the morning of August 1 1920, when Bal Gangadhar Tilak passed away in Bombay, India lost not just a leader but a towering figure who had prepared the soil on which Gandhi’s mass movement would soon grow. For millions of Indians, Tilak was not merely a politician but the very embodiment of resistance. To his admirers, he was Lokmanya – accepted by the people as their leader. To the British colonial authorities, he was the dreaded “Father of Indian Unrest.” A century later, his life continues to illuminate the early struggles of India’s independence movement.

Born on July 23 1856, in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, Tilak belonged to a Chitpavan Brahmin family. His father was a Sanskrit scholar and a school teacher, and his early upbringing imbued him with a deep respect for learning and tradition. But Tilak’s destiny was not confined to the life of a scholar. After earning a degree in mathematics from Deccan College and later in law, he briefly took up teaching. Soon, however, his restless energy led him to journalism and public life. He was determined to shape a new India – educated, self-reliant, and politically awake.

Tilak firmly believed that education was the key to awakening the Indian mind. In 1880, along with Gopal Ganesh Agarkar and Vishnushastri Chiplunkar, he co-founded the New English School in Pune. This institution was a mission to instil national pride among young Indians. The venture soon expanded into the Deccan Education Society, which went on to establish Fergusson College. Through these institutions, Tilak hoped to build a generation that would question colonial dominance and stand up for India’s dignity.

But Tilak soon realised that education alone was insufficient if it did not find an echo in public life. He turned to journalism as his second weapon. In 1881, he launched Kesari in Marathi and The Marwari in English. These newspapers became instruments of awakening, reaching beyond the classrooms to the homes and streets of Maharashtra. Through fiery editorials, Tilak critiqued colonial policies, championed Indian traditions, and called for resistance. His pen, the British realised, was as dangerous as any weapon.

It was in the pages of Kesari that Tilak first declared the immortal slogan, “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it.” To Indians still hesitant about demanding complete self-rule, this was a thunderclap. Unlike the early leaders of the Congress, who believed in gradual reforms through petitions, Tilak argued that nothing short of self-government would restore India’s dignity.

Tilak proposed his famous trisutri or three-point programme: Swaraj (self-rule), Swadeshi (use of indigenous goods), and National Education (rooted in Indian culture and taught in the vernacular). This was not abstract idealism but a practical roadmap to resist British control while reviving Indian self-confidence.

The partition of Bengal in 1905 by Lord Curzon added fuel to the nationalist fire. Tilak encouraged the boycott of foreign goods, the organisation of Swadeshi enterprises, and popular mobilisation. The movement was now psychological – a call to Indians to shed inferiority and reclaim their heritage.

By the early 1900s, the Indian National Congress had split into two factions: the Moderates, led by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who still believed in petitions and dialogue, and the Extremists, led by Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, and Lala Lajpat Rai. Together, this trio – Lal, Bal, and Pal – became symbols of uncompromising nationalism. Tilak’s differences with the Moderates were sharp. While he admired Gokhale personally, he could not accept the belief that Indians should simply wait for reforms to be handed down by a benevolent British government. At the Surat Congress of 1907, the clash became irreconcilable, and the party formally split. The Extremists, led by Tilak, now represented the impatient youth of India, eager to act rather than plead.

Tilak’s writings and speeches inevitably brought him into conflict with colonial law. He was tried three times on charges of sedition – in 1897, 1909, and 1916. The most famous of these was the 1908 case, when his defence of the revolutionaries Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki in Kesari was deemed an incitement to violence. The judge, Dinshaw Davar, sentenced him to six years of rigorous imprisonment in Mandalay, Burma.

Tilak’s response in court has since become part of nationalist memory:

“In spite of the verdict of the jury, I maintain that I am innocent. There are higher powers that rule the destiny of things, and it may be the will of Providence that the cause which I represent may prosper more by my suffering than by my remaining free.”

Far from breaking his spirit, the years in Mandalay transformed him into a philosopher. In prison, he wrote his monumental work, the Gita Rahasya, a reinterpretation of the Bhagavad Gita as a call to action rather than renunciation. For Tilak, true religion meant duty to one’s country and people – a doctrine he termed Karma-Yoga.

When Tilak was released in 1914, he was in poor health but unbroken in will. The political scene in India had changed with the onset of the First World War. Tilak threw himself back into politics, founding the Home Rule League in 1916, alongside Annie Besant. Travelling across villages, he mobilised support among farmers, workers, and common people, giving the independence movement a genuinely mass character. It was also during this period that he attempted to bring unity between the Moderates and Extremists through the Lucknow Pact of 1916. This agreement, which also involved the Muslim League, marked a rare moment of Hindu-Muslim unity against the British. Though differences would later reappear, Tilak’s efforts had laid the groundwork for broader cooperation in the struggle.

Tilak believed that political freedom was inseparable from cultural and social revival. He transformed the private celebration of Ganesh Chaturthi into a public festival in 1894. Through processions, speeches, and cultural programmes, the festival became a tool of national awakening, bringing people together across caste and class lines. Similarly, he organised the celebration of Shivaji Jayanti, reviving pride in the Maratha hero as a symbol of resistance to foreign rule.

Tilak also understood the power of economic nationalism. His call for Swadeshi was not limited to boycotting foreign goods but extended to building indigenous enterprises. He set up the Paisa Fund, collecting contributions to promote Indian-owned industries. In many ways, this was an early vision of what we today call Atmanirbhar Bharat.

When Tilak died in August 1920, Mahatma Gandhi, then preparing to launch the Non-Cooperation Movement, called him “the Maker of Modern India.” Thousands thronged the streets of Bombay to pay their last respects, and for days the city stood still in mourning. Tilak had not lived to see the India of his dreams, but he had contributed to the creation of the atmosphere in which independence became inevitable. His slogan of Swaraj, his strategy of Swadeshi, and his emphasis on cultural pride continued to guide the national movement long after his death.

Comments