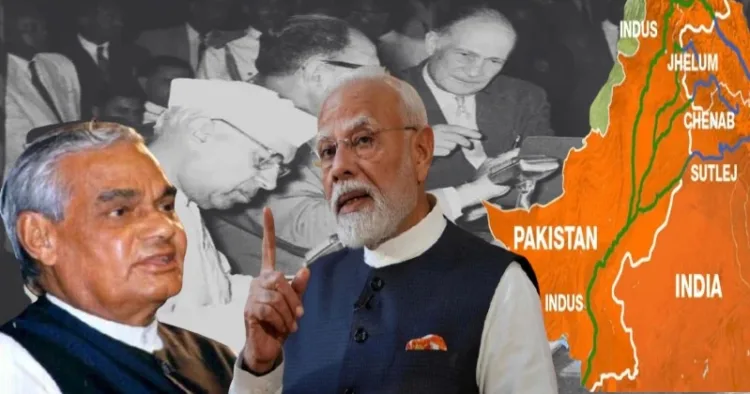

History repeats itself. Yes, it does sometimes and on such occasions it does to the last dots and details. During the ongoing monsoon session of Parliament, Tuesday (July 29) was one such day. The proceedings of the day included Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speech in which he spoke about putting Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance. Accusing the opposition Congress of often bartering away the nation’s interest, he criticised Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru sharply.

By putting the IWT in abeyance, his government has tried to correct a historical wrong committed under the watch of Pandit Nehru, Modi said. The allotment of 80 per cent of waters to Pakistan and only 20 per cent to India proved it amply that Bharat’s interests were frittered away in the IWT. In fact, nowhere in the world is such a Treaty to be found where the upper riparian country takes such a beating as to concede 80 per cent of waters to the lower riparian.

“It has been an old habit of the Congress to mortgage India’s interests. The biggest example of this is the Indus Waters Treaty. Who signed this treaty? Nehru did it and granted rights to 80 per cent of the waters of the rivers originating in India and flowing to Pakistan,” Modi said, amid shouting and protests from the Congress and its allies.

In an unprecedented historic move, India has put the IWT in abeyance in the best interests of its citizens and farmers. “India has firmly conveyed its stance that blood and water cannot flow together,” he said. PM Modi had articulated this stance for the first time in September 2016 after the infamous Uri (Baramullah) terrorist attack on an Army camp. Around that time, a special group was also set up to examine the IWT in depth and give its inputs.

“The previous Congress-led Governments neglected the Indus Waters Treaty and failed to address the mistakes made during Nehruji’s era. However, today, India has taken decisive action to rectify those errors,” PM Modi said. He said India gets its identity from the Indus River, but Nehru and the Congress allowed the World Bank to decide on the sharing of the waters of the Indus and the Jhelum. It needs to be mentioned here that the Indus River, from which this Treaty derives its name, flows in the Leh district of the Ladakh region. From there, its flows into Pakistani territory after Zanskar river meets it at Sangam, 40 km outside Leh town.

“Nehru signed this Treaty that granted rights to 80 per cent water to Pakistan and 20 per cent to a big country like India. What kind of diplomacy is this?” PM Modi asked. It indeed was nothing else but weakness on the part of Nehru that brought this upon Bharat. Incidentally, Nehru told the Indian negotiating team of engineers and other officials, headed by N D Ghulati, that they should be very generous towards Pakistan on this question of water sharing, or water division. This, Nehru said, was likely to soften Pakistan’s stance towards Bharat and help resolve many issues, including J&K, with it.

Contrary to these Nehruvian hopes which were soon belied, Pakistan only became more greedy after the Treaty. Speaking on the issue of IWT on November 30, 1960, in Parliament, young Jan Sangh MP from Balrampur Atal Behari Vajpayee said the words of Pakistan President Ayub Khan on IWT were subject to dangerous misinterpretation by Pakistan.

Pakistan’s President Ayub Khan had then said, and these words were quoted verbatim by late Atalji. Ayub had said: By accepting the procedure for joint inspection of the river course, India has, by implication, conceded the principle of joint control extending to the upper region of Chenab and Jhelum, and joint control comprehends joint possession. If these words of Ayub were accepted at face value, the consequences for Bharat would be very dangerous, the Jan Sangh MP warned Nehru.

Atalji further said: Under the international law, it is not incumbent and mandatory for Bharat to give that much water to Pakistan. Besides, Pakistan is no position to utilise this water by building the necessary infrastructure for its own benefit. If Nehru had not instructed the negotiating team to adopt this stance of generosity towards Pakistan, it could have forced Pakistan to agree to far less waters of the Indus system. Ayub Khan is on record having said that if Nehru had not intervened in the negotiations, there would have no treaty.

He added: I don’t know what the stumbling block in the negotiations was that Prime Minister Nehru removed leading to such a lopsided treaty. I want to state here that conceding wrong and exaggerated demands of Pakistan is not the right way to establish amity, friendship or cordial relations. If we concede a wrong demand being made by Pakistan, it must be opposed and a principled stance taken against it. If this leads to hostility and ill-will from Pakistan, it is clear that Bharat can never establish cordial and good neighbourly relations with it, Vajpayee had said in that debate in November 1960.

Further elaborating on the points he had made, Vajpayee said that it is so unfortunate that relations are being established and compromises are being made with Pakistan without taking Parliament into confidence. I do concede that the government has a right to enter into any agreement with another nation. However, I want to state here that apart from this legal, technical stance, the government should take Parliament into confidence. This is because the government decisions are not only administrative but they have a wide impact on the security of the nation and also its economy.

Vajpayee also talked at length about healthy democratic practices that the government of the day should foster and encourage. He said the government has entered into an agreement with Pakistan on running a train. The government has agreed to finalise a deal on Beribari. It has also entered into an agreement, a treaty no less, on river and canal waters. All this has been done when Parliament was in session and most members were available to hear the government version. However, the government decided to ignore Parliament and go ahead on all these points. This was no way to promote healthy democratic practices and precedents, Vajpayee said.

At the end of his speech in Parliament, Vajpayee suggested that the Nehru government should add the question of unsettled payments to be taken from Pakistan into IWT negotiations. By this, he meant that Pakistan should be made to pay seniorage charges for use of the waters of the Eastern Rivers. This period was a significantly long one starting from April 1, 1948, till the date waters of the Eastern Rivers were stopped from flowing into Pakistan. The significance of seniorage charges lie in establishing the sovereignty of India over the rivers, even if the amounts received on that account were not to be very substantial.

In his speech on Tuesday, PM Modi said in Parliament had the Treaty not been signed, several projects could have been built on the west-flowing rivers to solve the problems of farmers in states, such as Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi. “India could have generated more electricity and solved its problem of drinking water shortages,” Modi said, contending that the Treaty had led to inter-state water disputes in the country.

Indirectly, he was referring to inter-state disputes over sharing of waters that have been there between Punjab and Haryana, of Punjab with J&K besides Rajasthan facing water shortages. There have also been problems on the issue of water sharing between the national capital Delhi and neighbouring Haryana. Getting more share of Indus system of waters, particularly from the Chenab, could have mitigated many of these problems. In fact, they would not have arisen in the first place.

The Prime Minister slammed Nehru for giving crores of rupees to Pakistan to build canals on the Indus and other rivers, and giving up India’s rights to de-silting the dams built on its territory on these rivers. It needs to be mentioned here that for the construction of “replacement canals’’ on the Western Rivers at that time, Bharat had contributed Rs 83 crore in invaluable foreign exchange and gold much to the chagrin of many MPs, including that of the Congress. These MPs had criticised Nehru for unnecessarily paying this huge amount to Pakistan.

Incidentally, at today’s exchange rates, this amount of Rs 83 crore will come to thousands of crores. For a casual estimate of how humongous this amount was at that time, it can be mentioned here that the rate of gold in 1960 was around Rs 112 per tola (10 gm). At present, the gold rate is over a lakh rupees per tola (10 gm).

Modi said Nehru had admitted his mistake later and said he believed that the Indus Waters Treaty would lead to the solution of other problems with Pakistan. “But he (Nehru) realised that the problems remained as they were,” he said. He was then referring to the conversation ND Ghulati, chief negotiator of the Indian team, had with Nehru the day Ghulati was retiring.

In his seminal book on the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), published in the year 1973, and out of print for about two decades or more now, Ghulati has given details about his meeting with Nehru. Ghualti has recorded that Nehru was very upset about the Treaty later. When Ghulati went to meet Nehru on his last day in office, Nehru admitted to him that all his hopes of a détente, or cordial relations with Pakistan, based on generosity shown during Treaty negotiations, had proved to be unfounded and incorrect.

Ghulati has gone to the extent of writing that this was one huge error of judgment about Pakistan which Nehru regretted to the end of his life years later. He says that the sense of guilt that this signing of IWT created in Nehru was responsible for his brooding nature and ill health in later days.

Comments