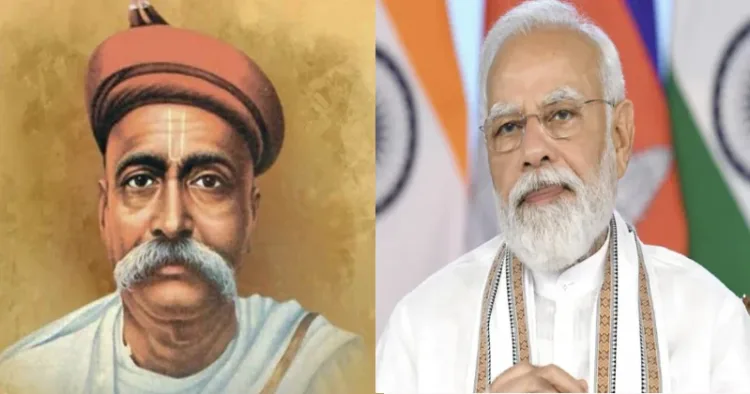

On July 23, Prime Minister Narendra Modi took to X to pay homage to one of the tallest figures of Bharat’s freedom movement Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak on his birth anniversary. The Prime Minister described Tilak as a “pioneering leader who played a vital role in kindling the spirit of India’s freedom movement with unwavering conviction” and hailed him as an “outstanding thinker who believed in the power of knowledge and serving others.”

Remembering Lokmanya Tilak on his birth anniversary. He was a pioneering leader who played a vital role in kindling the spirit of India’s freedom movement with unwavering conviction. He was also an outstanding thinker who believed in the power of knowledge and serving others.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) July 23, 2025

As India today continues to grapple with the legacy of colonial institutions and the ongoing tension between dharma and modern statecraft, the life of Bal Gangadhar Tilak offers a powerful historical reference point. A fiery nationalist, philosopher, educator, and journalist, Tilak redefined the very essence of political resistance by infusing dharma and cultural resurgence into the political discourse, challenging not just British imperialism but also the spiritual and psychological subjugation of an ancient civilisation.

Born on July 23, 1856, in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, Tilak emerged from a scholarly Chitpavan Brahmin family steeped in Sanskrit learning. After graduating from Deccan College in Pune with degrees in mathematics and Sanskrit and earning a law degree from the University of Bombay in 1879, Tilak made a decisive shift toward education and mass awakening.

He co-founded the Deccan Education Society in 1884, a bold attempt to liberate Indian minds through liberal English education. But when he discovered deviations from the ideal of selfless service among fellow educators, Tilak resigned—a gesture symbolic of his lifelong commitment to personal integrity and national ethics.

He soon launched two powerful newspapers Kesari (in Marathi) and The Mahratta (in English)which became rallying platforms for an awakened national consciousness. Through scathing editorials, he denounced British tyranny and criticised moderate Congress leaders who advocated gradual reform over full independence.

Tilak’s genius lay in recognising that politics devoid of cultural roots is impotent. At a time when the nationalist movement was largely confined to the English-speaking elite, Tilak used Hindu religious symbolism and popular festivals to democratise the movement.

In 1893, he organised Ganesh Utsav, transforming a private family ritual into a mass celebration of unity and resistance. Two years later, he revived the memory of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, invoking the Maratha warrior king as a symbol of Hindu resurgence and defiance against oppression.

While critics from the liberal and Marxist camps later accused him of communalising the freedom struggle, it must be remembered that Tilak’s approach was inclusive of all Indians, yet unapologetically rooted in dharma and indigenous traditions. He did not politicise religion; rather, he spiritualised politics.

The British government, threatened by his rising influence, arrested Tilak in 1897 on charges of sedition. His fiery editorials in Kesari were deemed inciteful after the Chapekar brothers assassinated plague commissioner W. C. Rand. His imprisonment made him a national icon, earning him the title “Lokmanya” beloved leader of the people.

Released after 18 months, Tilak plunged into active resistance again, especially during the 1905 Partition of Bengal. He spearheaded the boycott of British goods and laid down the Tenets of the New Party, advocating passive resistance, economic self-reliance, and civic courage. These ideas would later become foundational to Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha movement.

At the Surat Congress of 1907, Tilak’s hardline stance led to a split with moderates. The British pounced again, this time deporting him to Mandalay, Burma, for six years. Yet prison only sharpened his intellect. There, he authored his magnum opus—‘Shrimad Bhagavad Gita Rahasya’, rejecting the colonial and renunciate interpretation of the Gita, asserting instead that karma yoga and selfless action were the true messages of the sacred text.

Returning in 1914, Tilak founded the Indian Home Rule League, asserting that “Swarajya is my birthright and I shall have it.” In 1916, he concluded the Lucknow Pact with Mohammed Ali Jinnah, advocating Hindu-Muslim unity against British rule—decades before Partition would sour such alliances. This pact was a rare moment of political alignment that underscored Tilak’s pragmatism in uniting India across community lines.

His 1918 visit to England as the League’s president revealed his deep understanding of geopolitics. Sensing the rise of the Labour Party, he forged relationships that later paid dividends when India finally attained independence in 1947 under a Labour government.

Yet, he maintained a clear moral boundary always disavowing violence, even while advocating mass resistance.

Tilak’s was not a theocracy. It was an Indic civilisational model where knowledge (jnana) and righteousness (dharma) informed power (rajya). He understood the dangers of dharma being used for political gain, insisting that the saint must guide the king, not the reverse. His model preserved the moral authority of spiritual traditions while resisting both colonial and communal distortions.

Tilak passed away on August 1, 1920, just as the freedom movement was entering its Gandhian phase. More than just a revolutionary, Tilak was a civilisational revivalist. He stood as a bridge between the Vedic past and a sovereign future, between cultural assertion and political emancipation.

Comments