On May 7, the Allahabad High Court declined to quash criminal proceedings against four individuals accused of unlawful religious conversion, ruling that the charges are serious and warrant police investigation. The case, which centres around alleged forced conversions to Christianity in the Jaunpur district, has reignited debate on the interpretation of the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion Act, 2021.

The order was passed by Justice Vinod Diwakar while hearing two applications filed under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. One of the petitions was moved by Durga Yadav, who has been identified as the main orchestrator of the conversion activities. Three others — Govind Lal, Jitendra Kumar, Surendra Gautam, and Usha Devi — were also named in the FIR (335/2023) registered at Kerakat Police Station in 2023. Based on the complaint, the accused party was booked under sections 5(1) and 3 of the Uttar Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act alogwith sections 419, 420, and 508 of the IPC.

Police Intervention and Seizure of Conversion Material

According to the case diary, the police acted on confidential information about illegal conversion activities taking place at a church in Vikrampur village. Upon reaching the site, the police found a man addressing a gathering and persuading attendees to convert to Christianity by promising financial support and free medical treatment.

As police entered the premises, the crowd began to disperse. However, four individuals were apprehended at the scene. A thorough search of the premises led to the seizure of religious literature and conversion-related material including nine large Bibles, several pamphlets, envelopes, musical instruments, and a camcorder microphone.

The detained individuals named Shravan Kumar, a local pastor and husband of accused Usha Devi, as the person who fled the scene. They also identified Durga Yadav, pastor of Bhullan Deeh Church, as the chief planner who provided money and material for the conversion drives.

Notably, they further confessed that they, along with others, were involved in persuading local and distant people to convert to Christianity by offering money and free medical aid. They also stated that their leader is Durga Yadav, son of Sampat Yadav, resident of Bhullan Deeh, Chandvak Police Station, Jaunpur District, who is also the pastor of the Bhullan Deeh Church, and instructed them to convert innocent people and provided money and religious conversion-related materials.

Witness Accounts Support Police Findings

The Court took note of detailed victim testimonies during the investigation, including that of Gautam Yadav from Mahadeva village, who alleged he was lured with money, medicines, and fear of calamities to convert to Christianity.

In his statement, Gautam Yadav said: “Shravan Kumar and his team, including Jitendra Ram and Ajay Bhardwaj, were persuading people from several villages under the jurisdiction of Kerakat and Chandwak police stations to embrace Christianity. They threatened and harassed me with inducements and fear. All materials used for the conversions were supplied by Durga Yadav.”

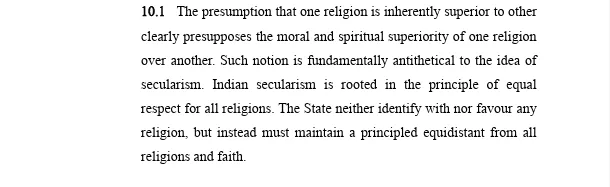

Court on Secularism and the Role of the State

In a strongly worded judgment dated May 7, 2025, Justice Vinod Diwakar underscored the constitutional balance between religious freedom and public order. He wrote, “The presumption that one religion is inherently superior to other clearly presupposes the moral and spiritual superiority of one religion over another. Such notion is fundamentally antithetical to the idea of secularism. Indian secularism is rooted in the principle of equal respect for all religions. The State neither identify with nor favour any religion, but instead must maintain a principled equidistant from all religions and faith.”

The Court clarified that Article 25 of the Constitution guarantees the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, but this freedom is subject to public order, morality, and health. Forced or fraudulent conversions, it noted, are not protected under the guise of religious propagation.

“Unlawful conversion is not only an offence against an individual and their relatives, but also the State — particularly in cases of mass conversion of socially and economically deprived sections of society,” the Court observed. “In such circumstances, the State cannot remain a silent spectator.”

Broader Interpretation of “Aggrieved Person”

A significant point of contention in the case was whether the Station House Officer (SHO) who lodged the FIR could be considered an “aggrieved person” under Section 4 of the Act. The defence argued that only direct victims or their relatives are empowered to file a complaint.

However, the Court ruled in favour of a broader, purposive interpretation, stating, “The undefined term ‘any aggrieved person’ under the unamended Section 4 of the Act, 2021, must be construed broadly to include the Station House Officer, who is legally mandated to maintain public order and is competent under Section 173 of BNSS, 2023 to register FIR for cognizable offences.”

The Court emphasised that a narrow interpretation would defeat the legislative intent and render the law ineffective in preventing mass conversions.

Dismissal of Plea and Trial Directions

Dismissing the plea for quashing the FIR, the Court stated, “The allegations made in the FIR and the victim statements constitute a cognizable offence justifying the registration of the case and the investigation thereon. This case does not fall in any category that would warrant the exercise of inherent powers of the High Court to quash proceedings.”

Justice Diwakar further noted that although the applicants had not been arrested, they would be subject to the trial court’s directions. If they failed to cooperate, the court could proceed in accordance with the law.

It is noteworthy that the rate of missionary conversion in India and across the globe is at all time high with their religious leaders claiming that ‘The faith has been declining.’

Christianity across the Globe

According to the 2013 report Christianity in its Global Context, 1970–2020: Society, Religion, and Mission by the Centre for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, the Christian faith has seen a marked expansion across the globe, especially in the Global South.

In 1970, just 41.3 per cent of the world’s Christians lived in the Global South, which includes Africa, Asia, and Latin America. By 2020, that share had surged to 64.7 per cent, signalling a dramatic geographic shift in Christianity’s centre of gravity from the Global North to the South.

Asia, although still the least-Christian major region by percentage, has witnessed steady growth. In 1970, Christians made up only 4.5 per cent of Asia’s population. That figure rose to 8.2 per cent by 2010 and was projected to reach 9.2 per cent by 2020. This represents a 104.4 per cent increase in Christian population share in Asia over the 50-year period.

Between 2010 and 2020 alone, Christianity in Asia grew at an annual rate of 2.1 per cent, more than double the general population growth rate of 0.9 per cent, a trend largely driven by conversions through missionary efforts.

In India, much of this growth is fuelled by hidden Hindu believers in Christ, so-called crypto-converts, who have been nurtured through underground missionary networks. Across Asia, Independent churches are projected to surpass Roman Catholics by 2020, with 3.7 per cent of the population identifying as Independents compared to 3.5 per cent as Catholics. Notably, Independents have grown at an annual rate of 4.8 per cent from 1970 to 2020, the fastest growth among all Christian traditions in the region.

The Role of Crypto-Converts

A key driver of Christian growth in India and Asia is the rise of crypto-converts—hidden believers from Hindu, Muslim, or other backgrounds who practice Christianity covertly, often guided by missionaries. In India, where Christians make up just 2.3 per cent of the 1.4 billion population (with 18 per cent in Kerala), the presence of these covert Christians, alongside missionary-led underground communities, suggests that Christianity’s true extent is underreported. Missionaries have been pivotal in fostering these communities, particularly through the growth of Independent churches and “house church” movements, which offer flexible, culturally resonant expressions of faith.

The Christianity in its Global Context report highlights that global religious adherence has risen from 82 per cent in 1970 to 88 per cent in 2010, projected rise of 90 per cent by 2020, partly due to religion’s resurgence in China. Christianity and Islam are expected to account for 57.2 per cent of the global population by 2020, up from 48.8 per cent in 1970, as per the report.

As per the report In the global South, Christianity is outpacing population growth, while in the global North, particularly Europe, it is declining amid shifts to agnosticism and atheism. Asia, the world’s most religiously diverse continent, hosts nearly all major religions, including 98.4 per cent of global Christians in 2010, making it a focal point for missionary activity.

Indian Census and Global Reports+

While Christianity has surged across Asia, fuelled by aggressive missionary networks and the rapid rise of Independent and Protestant house churches, India’s official figures tell a vastly different story. According to the 2011 Census data, Christians made up 2.3 per cent of the population, around 2.78 crore people, in a nation of over 121 crore. In contrast, the Christianity in its Global Context report outlines a dramatic Christian expansion across East and Southeast Asia, especially in Asia, where they rose from 1.2 per cent in 1970 to 8.1 per cent in 2010, with projections reaching 10.5 per cent by 2020. Even in South-central Asia, where India is said to be at the heart of this growth, Christianity expanded at a rate outpacing population growth. These global projections, however, stand at odds with India’s census-based reality. Much of the supposed growth in India is attributed to “crypto-converts,” meaning the Hindus who secretly practice Christianity but retain Hindu identities to avoid legal and social backlash.

Unlike the transparent religious transitions elsewhere in Asia, India’s Christian expansion is largely subterranean, bypassing legal scrutiny and exploiting social vulnerabilities. What appears to be a religious phenomenon is, in fact, a strategic and covert transformation, raising alarms about the erosion of India’s cultural cohesion and the silent recalibration of its religious landscape, hidden behind unchanged official numbers.

Comments