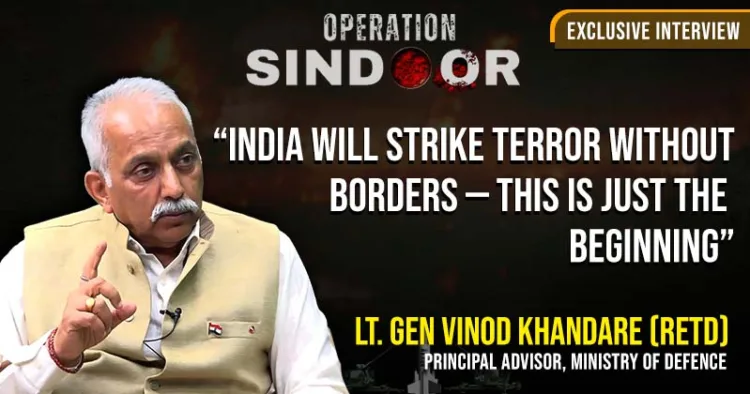

In the wake of Operation Sindoor, a decisive military response following the Pahalgam terror attack, the nation has been closely watching diplomatic manoeuvres, strategic signals, and the Government’s evolving posture. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has clarified that the operation is only paused, not ended, raising critical questions about ceasefire status, third-party involvement, and India’s next steps. To decode these developments, Organiser Editor Prafulla Ketkar sat down with Lt. Gen. Vinod G Khandare (Retd.), Principal Advisor to the Ministry of Defence and former Director General of the Defence Intelligence Agency, for an in-depth and forthright conversation. Excerpts:

Your first thoughts on Operation Sindoor and its military objectives?

What a brilliant masterstroke in naming the operation – ‘Sindoor.’ It emotionally unified the nation by invoking our civilisational respect for women—especially after a newly married woman was made a widow. It truly became a “whole of nation” moment. Traditionally, wars were expected to be short and intense, with warning periods and structured initiation like in 1971. But this conflict was different. We did not restrict ourselves to the Line of Control (LoC). We stretched the adversary across multiple fronts.

Think about the Gulf War or Israel’s recent actions—high-tech, precise, and remote. Now look at this operation: Not a single aircraft or soldier crossed over, yet targets were hit with pinpoint accuracy. It showcased how you can minimise losses while using satellite convergence, sensors, and precision to strike strategic assets like Mianwali, Sargodha, and Bolari.

What began as a tactical response became a strategic mission. The Prime Minister, NSA, CDS, and service chiefs operated in complete synergy. Cyber information, and narrative warfare were seamlessly integrated. Phase 1 of the operation achieved its goals through careful escalation. By May 10, the adversary reached out to de-escalate. We maintained control and made it clear, our fight is against terrorism, and we won’t be bound by geography when it comes to neutralising that threat.

There was pressure after the Pahalgam attack. The public expected immediate action, yet we took time. How do you view that?

Actually, the human psyche tends to compare with past wars. People recalled the surgical strikes, Pulwama, and Balakot—wondering how quickly we responded then. Even Pakistan expected something similar, in terms of timing or geography. But repeating the same response wouldn’t have achieved more.So when people expected action within 24 hours or a week, we had to go beyond. Repeating the same playbook was not enough. Pahalgam needed a different response. This time, we struck at multiple locations, not just one like Balakot. It was an integrated operation, along LoC, deep into Punjab, Sindh and even the Navy was redeployed. The Navy had just finished exercises, had to refuel, reload, and return. That alone took time. Coordinating such a response involves not just planning action, but anticipating enemy reaction. That requires preparation. Possibly for the first time since 1971, civil defence was activated. The Home Ministry and state police DGPs got involved. So yes, it took time, but it was essential. And I believe it was the optimal use of time.

From URI to Balakot to now, the operational depth has increased. Crossing the LoC, International Border, and now hitting deep into Pakistan. How do you explain this evolution?

See, the choice this time was clear. We had to strike from the air. On the ground, we held and intensified along the LoC, knowing he had ammunition and fuel shortages. That kept him engaged there. Meanwhile, the military carefully selected targets using intelligence from RAW and National Technical Research Organisation, verifying human inputs with technical data. Experts on both sides were involved to ensure accuracy.

The idea behind striking across a wide expanse—from Sargodha to Bolari—was to tie him down. If you hit both, troops at either end can’t move. That spreads him thin, and it’s smart, given Pakistan’s narrow geography. They have always spoken of strategic depth, we have now denied them that. And by pressing near their nuclear assets, whether announced or not—we have called their bluff. With the kind of decisive leadership we have, everything was planned in precise detail. The chances of error were minimal. Ultimately, we stretched him strategically. And within three days, he had to make a call to our DGMO.

On the 6th and 7th night, strikes were conducted. But the response from Pakistan post-attack, drones, missiles, air attempts was unexpected. How did we maintain the upper hand in this escalation ladder?

One key lesson from last time was about target selection. In Balakot, we struck in a remote area, leading many, including our people, to question if we really hit anything. That was disheartening for armed forces officers. So this time, we struck central locations, precisely targeting what they called the markaz. It was visible, undeniable. Last time, even after stopping, Abhinandan was captured, and things escalated. We expected a similar retaliation now. But knowing we had S-400, they avoided using aircraft and instead launched drones—helped openly by China, Turkey, even Azerbaijan. These drones targeted civilians in Poonch, Rajouri, Barmer, even places of worship like Gurudwaras and in Uri too, Muslims were hit, so much for Asif Munir’s two-nation theory statement. We never retaliated against civilians. We hit military targets. Once he crossed the line, we escalated: hit radars, anti-air systems, runways, ATCs, hangars. Two airfields he considered “red lines” were struck, so he ran to the US. This was also part of conflict management. We warned him at each step. And when he couldn’t take more, he sought third-party help. But we stayed firm: no third-party talks. We maintained control and the moral high ground—with our commitment to bilateral conflict resolution. Once again, we remained on top.

The role of Atmanirbhar Bharat and Made-in-India defense tech was visible. How do you see this transformation?

Over the past 15 years, most of our defense inventory came from a single superpower. After the Cold War and the USSR’s collapse, we became dependent on countries like Ukraine, Russia, and Bosnia. Since inventory can’t be replaced overnight, two key decisions were made: diversify sources and push for Atmanirbharta. Earlier, we relied on Transfer of Technology, but it was slow and costly. Now, with technology cycles shortening every 18 months, we shifted to Joint Ventures, like BRAHMOS, AK-203, and C295 with Airbus—which are proving successful. Both public and private sectors are being engaged through these models. To boost Atmanirbharta, the government earmarked funds for indigenous purchases. Once basic design and development are achieved, Indian industry can handle production. The services are working with a clear timeline—items ready today, in 6 months, 1 year, or 3 years; so import control improves, reducing external dependency.

“Taking PoJK or pushing for Balochistan’s independence would need deliberate planning, global narrative-shaping, and extensive preparation”

COVID–19 exposed our vulnerability in areas like semiconductors, prompting swift correction. In this conflict too, we saw where we need further control. Systems like Akash, BrahMos, and loitering drones showed the strength of indigenous tech. Future wars may differ, so we are re-evaluating needs mobility, comms, firepower, precision, surveillance—and using capital and emergency procurements to bridge gaps. All three services are aligned on Atmanirbharta now. If we were dependent on a country like the United States, they could have cut us off. But this time, they couldn’t, proving our approach is right, though more needs to be done. In fact, many Indian startups and MSMEs already export components to Israel, UK, USA, and Germany. While we may not yet produce full systems, we are strong in parts and production. Even our artillery shells are being used abroad after being filled elsewhere. The next focus must be R&D. Private industry needs better incentives to invest. Without R&D, we can’t stay ahead of adversaries. Government is aware, and action is expected.

You talked about changing nature of war, and besides technology, another important aspect that has been talked about for a long time now—but it was more visible this time—one is the cyber, other is psy (psychological), and third is the information—rather disinformation, misinformation, whatever we want to call it. How to deal with this?

When we talk about the changing nature of war, we must look beyond kinetic warfare and focus on non-kinetic domains like the electromagnetic spectrum, information, and cyberspace. These aren’t separate—they must work in sequence. You can’t suddenly create cyber or information warriors; it requires sustained effort, generation after generation. There’s a misconception that cyber defense needs a formal army. But countries like Israel, Russia, and China rely on patriotic citizens who act without orders. China, for example, has a massive cyber force guided by the CCP, not a formal military structure. We’ll need something similar.

With 1.44 billion people and 1 billion internet users, there’s no formal training—but the key lies in understanding content. Every citizen must judge:

1. If it’s pro-India—share it.

2. If anti-India—question the sender and report it.

3. If uncertain—seek guidance from trusted elders or mentors.

This helps counter the tsunami of disinformation. Importantly, misinformation is accidental; disinformation is deliberate—and that’s what we are facing now.

Internally, this fifth front, narrative and information warfare is active. In a complex country like ours, it is easy to spark panic or disruption—whether through cyber, chemicals, or misinformation. Are we prepared? Our civil defense is improving significantly. Post-1971, for the first time, DGPs and the Home Ministry activated sirens, dug trenches, and trained schoolchildren. In 1965, we had blackouts. Today, many don’t even know what that means. The reality is: when war happens, it’s not just the military, nation go to war. Citizens must now become stakeholders in national defense.

You spoke about Point Five. With this fifth front of internal narrative warfare about which General Vipin Rawat also spoke of a 2.5 front war, and now possibly more, what’s your suggestion for tackling this expanding challenge?

The biggest challenge for any democracy is internal cohesion. With so much freedom and transparency, people expect to be informed before and after every government action, even in war. But that is not how wars are fought. Disclosing sensitive details puts lives at risk. We have seen this before, during Kargil and 26/11. Yet, people still demand information that could jeopardise operations. Self-regulation in the media has not worked. Strategic awareness must become part of our culture. In contrast, adversaries like China and Pakistan enforce strict information control, people follow orders without question. In India, everyone has their own narrative. We must build a strategic culture rooted in our traditions, like during the Maratha empire, where society remained resilient even when kings fell.

Today, the vision of Viksit Bharat 2047 demands national unity. Controlled conflict is also a strategic decision, not every provocation needs full war. We must punish swiftly, return to normalcy, and stay ready. War today isn’t just about rockets, it’s cyber, information, economy, and diplomacy too.

After the operation, many were surprised, some expected this to be the moment to take back PoJK or dismantle Pakistan. Media hype added to that perception. Also, the government never used the word ‘ceasefire,’ only terms like ‘pause’ or ‘stoppage of firing.’ Even the Prime Minister said, ‘It’s just a pause.’ What does that actually mean?

When we launched this action, we did not declare war, it was a limited conflict with a clear objective: hit terrorism. Once we did that, we waited to see how the adversary would respond, which they did by targeting civilians. And when our people suffer, we must respond. At no point did we say we’d break Pakistan or reclaim PoJK. Those ideas exist in public discourse and they should, in a vibrant democracy—but military actions must have defined goals. You escalate only when necessary. If continuing harms your economy, you pause, but stay prepared. That’s deterrence through demonstrated power.

Many assumed this was the “last chance” to take PoJK. Why last? Who is stopping us from acting later? This was a reaction, not a full-scale campaign. Taking PoJK or pushing for Balochistan’s independence would need deliberate planning, global narrative-shaping, and extensive preparation. Pakistan still influences platforms like the UN. So if we ever choose that path, it will be a different operation altogether, not a short punitive strike like this one.

With the firing paused and aggressive posturing reduced, how do you see our war on terror progressing from here, especially with diplomatic briefings underway?

Terrorism must be tackled both externally and internally. Internally, Rashtriya Rifles, J&K Police, and intelligence agencies have been active for decades and will likely intensify clean, precise operations to avoid collateral damage and prevent alienation. Along the IB and maritime sectors, the question is: how strong is our infiltration prevention? Here, it’s not just military—state police, BSF, intelligence agencies, even civilians must be involved. Drone sightings, smuggling, and tunnel detection need public vigilance. This is now a whole-of-nation effort. Marine Police capabilities must be independently audited. States must be asked: are they ready? Even on the eastern front—like with Bangladesh—we need to stay alert.

Terrorism hurts our people and economy. It is not just the military’s job. Citizens, especially beyond conflict zones, must be involved. State governments must step up too. While the military is handling operations, quiet doesn’t always mean peace. Communal, ethnic issues, and foreign funding in border states show deeper vulnerabilities. We must now look inward—do we need police reform? Structural fixes? The answer is yes.

Looking at the global scenario, do we sometimes get swayed by friendly posturing from big powers, only to face unmet expectations later? Are we heading back to a pre-Pokhran-like situation in global equations?

This phase has clearly demonstrated India’s strategic autonomy in foreign policy. We were not cornered, and on the issue of terrorism, most global powers sided with us, even if not publicly. No one opposed our strike on terrorist camps, barring the usual pseudo-intellectual voices.

Traditional diplomacy like exchanging dossiers has not worked, so we acted—and most countries remained silent. Later, global actors advised “restraint” and “calm”—but that was advice, not pressure. Like Israel or Russia, we too are free to decide our conflict’s end goals. Global powers prefer calm in this region due to commercial interests—especially arms sales. While India is moving toward Atmanirbharta, Pakistan relies on foreign military imports like JF-17s and J-10s. If one of these aircraft is lost in conflict, it affects global sales and stock value. This also fuels a propaganda war, often amplified by media that does not realise how defense economics work. Beyond India and Pakistan, other forces are manipulating perceptions, using even doctored images, to shift global arms market dynamics—deciding who should remain a supplier, and who shouldn’t.

Pakistan used a possibly doctored image of Adampur Air Base in their DGMO briefing, while the Prime Minister visited the same base, addressed troops, and sent a clear message. As a soldier, how do you see this contrast?

Today, satellite imagery makes verification easy. Global providers offer date-stamped images, just buy and check what Adam or Bolari looked like on any given day. India shared credible images during the DGMO Media briefing; Pakistan didn’t, likely to avoid being exposed. In such cases, not answering is also an answer. Geospatial intelligence is crucial in modern warfare—both for accuracy and to counter misinformation. Doctoring images is part of what I call “hyper-intelligence.” In contrast, the Prime Minister visited Adampur air base in person, S-400 visible behind him—boosting troop morale and sending a clear message. But disinformation is rampant. Our media space is filled with false narratives against our officers, leaders, and nation. Sadly, most netizens just scroll past it, mirroring a larger societal tendency to look away from wrongdoing. Our adversaries, however, rally together instantly. We must learn to fight back in the digital space. There is so much disinformation which comes up on the information highway. We have to learn to fight on the information highway. So what if you are trolled for some time? Doesn’t matter. But the nation comes first.

Do you see a doctrinal shift now, where any act of terror is treated as a potential trigger for a calibrated military response?

Yes, this is a major paradigm shift. We now ready to use power against any act of terrorism. But “any act” is graded; not every provocation warrants immediate retaliation. Our threshold will be decided internally—and kept unclear to the adversary. That uncertainty keeps them guessing: “Will this trigger a response?”. Maintaining that ambiguity is part of our strategic deterrence.

Comments