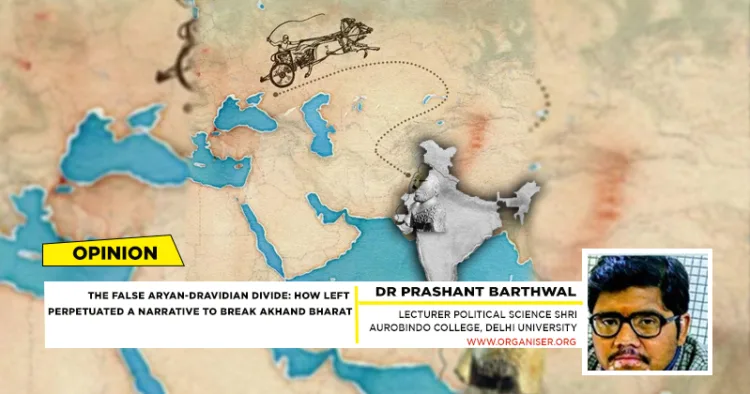

For millennia, Bharat has been a land that celebrated diversity while embracing a profound unity. From the Himalayan ranges in the north to the lush landscapes of the southern peninsula, Bharatvarsha has been held together by shared values, cultural heritage, and spiritual philosophy. Yet, in the 19th century, colonial powers, intent on dividing and ruling this vast land, introduced a divisive theory—the Aryan-Dravidian dichotomy. This theory, which asserts that a foreign Aryan race invaded and subjugated the indigenous Dravidian people, has since been used as a tool to foster divisions. What began as a colonial tactic was later adopted, adapted, and celebrated by left-leaning historians in post-colonial Bharat. They aim to fragment the idea of Akhand Bharat, undermining the civilisational unity that has bound this land together for millennia. The Aryan-Dravidian divide was not merely a scholarly hypothesis—it became a weapon. Marxist-influenced historians, especially those occupying influential academic institutions, pushed this narrative, often with political motivations that aimed to foster regional and communal tensions. Their goal was clear: to dismantle the idea of a culturally unified Bharat, thus weakening the concept of Akhand Bharat and creating divisions that could be politically and socially exploited.

The Aryan invasion theory finds its roots in the works of 19th-century European scholars, most notably Friedrich Max Müller. A German Indologist, Müller, popularised that a fair-skinned race of Aryans invaded Bharat around 1500 BCE, displacing the dark-skinned Dravidians, who were considered the original inhabitants. This theory, which found enthusiastic support among the British colonialists, provided a convenient explanation for Bharat’s diversity while justifying British rule as another ‘civilising’ force over a fragmented land. Max Müller’s works were replete with colonial biases, framing Bharatiya society in terms of racial hierarchies that mirrored European prejudices. Yet, despite being based on scant archaeological evidence and questionable linguistic assumptions, the Aryan invasion theory was embraced wholeheartedly by British administrators. The theory conveniently aligned with the British colonial policy of divide and rule, fostering regional and communal differences to weaken any potential for unified resistance. However, what began as colonial propaganda soon found resonance among a new breed of Bharatiya intellectuals. Inspired by Marxist historiography and eager to challenge the cultural ethos of ancient Bharat, left-leaning historians in post-independence Bharat began to perpetuate this false narrative. They turned the Aryan-Dravidian divide from a hypothesis into an established ‘fact,’ incorporating it into school textbooks and academic discourse. This became the starting point for a systematic assault on Bharat’s cultural unity.

The Marxist Agenda: Distorting History for Political Gains

At the heart of this intellectual betrayal lies the Marxist infiltration of Bharatiya academia. Starting in the 1960s and 70s, a group of left-leaning historians, often educated in the West and trained in Marxist theory, began dominating Bharatiya’s intellectual landscape. Romila Thapar, Irfan Habib, and D.N. Jha—scholars who identified themselves as secularists—became the torchbearers of this movement. Their historical analyses often ignored or undermined Bharat’s deeply spiritual and civilisational continuity, focusing instead on class struggle, regional conflict, and racial divisions. The Aryan-Dravidian divide fit perfectly within their framework, offering a convenient explanation for what they saw as Bharat’s fragmented past.

According to these left historians, ancient Bharatiya society was inherently oppressive, divided along rigid caste lines and marred by perpetual conflict between the Aryan and Dravidian populations. They ignored the fact that the concept of ‘race’ in ancient Bharat was vastly different from the racial theories that European colonialists imposed. In Bharat, distinctions were often based on geography, language, or cultural practices, not skin colour or racial identity, as understood in the West. However, leftist scholars, driven by their ideological convictions, turned a complex and nuanced history into a binary struggle between oppressors (Aryans) and oppressed (Dravidians). This narrative played perfectly into the hands of regional political movements, especially in South Bharat, where Dravidian identity politics gained momentum in the mid-20th century. The Dravidian movement, spearheaded by figures like Periyar and C.N. Annadurai, found in the Aryan-Dravidian divide, a powerful tool to assert their political agenda against what they saw as ‘Aryan’ domination from the north. Left historians provided intellectual legitimacy to these movements and actively encouraged this divisive discourse. Left-leaning historians, encouraged by their ideological leanings, found a convenient method to serve their political objectives in the Aryan-Dravidian narrative. The goal was not simply to study Bharat’s past but to reinterpret and reconstruct it in a way that justified a Marxist understanding of Bharatiya society. This reconstruction often involved dividing Bharat into warring factions and framing its past through the lens of class struggle, racial conflict, and exploitation—ignoring the cultural and spiritual unity that has historically defined Bharat. One of the critical platforms for this rewriting of history was the academic dominance of Marxist historians in prestigious institutions.

For these historians, the Aryan-Dravidian divide became a key tool to challenge and dismantle what they saw as the Brahmanical dominance of Bharatiya history and culture. By painting Aryans as ‘foreign invaders’ and Dravidians as ‘original inhabitants,’ they could reframe the Bharatiya civilisation as one rooted in racial and ethnic conflict rather than cultural continuity. This narrative served a dual purpose. First, it allowed them to challenge the notion of a unified Hindu culture that stretched from the Vedas to the present day. Second, it provided intellectual support to regional political movements that sought to assert their identity by distancing themselves from the broader Bharat or ‘Hindu’ identity. In particular, this narrative found fertile ground in Tamil Nadu, where the Dravidian movement had long sought to assert its political autonomy and distinctiveness. Figures like E.V. Ramasamy, popularly known as Periyar, used the Aryan-Dravidian divide to attack what he saw as the dominance of Brahmins and northern ‘Aryan’ culture. Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement and later the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) drew heavily from the leftist reinterpretation of Bharatiya history, adopting the view that northern Aryans subjugated southern Bharat, and this subjugation continued into the modern era through caste-based oppression. What leftist historians failed to acknowledge was that this narrative was fundamentally flawed. It was based on a superficial reading of Bharatiya history that ignored the deep cultural interconnections between northern and southern Bharat and the rich social mobility and reform traditions within Hinduism. Instead, they focused on a reductive and often anachronistic portrayal of Bharatiya society as a static, oppressive system, divided along racial lines. By perpetuating this myth, they played directly into the hands of separatist movements that sought to weaken the idea of Akhand Bharat.

The most insidious aspect of the leftist historiography around the Aryan-Dravidian divide is the deliberate distortion of facts to fit a predetermined narrative. In their eagerness to promote a Marxist reading of Bharatiya history, left historians often ignored or misrepresented evidence contradicting their theories. This was particularly evident in the way they approached the question of caste. While it is true that caste has been an important aspect of Bharatiya society, left historians exaggerated its role and portrayed it as an immutable system imposed by Aryan invaders on a hapless Dravidian population. This view ignored the fluidity of caste relations in ancient Bharat, as well as the numerous social reform movements within Hinduism that sought to challenge caste-based discrimination. Figures like Buddha, Mahavira, and later saints from the Bhakti and Sant traditions were all products of a vibrant tradition of social reform within Hinduism, which leftist historians often downplayed or ignored. This distortion of history also extended to school textbooks, where the Aryan-Dravidian divide was presented as an unquestionable fact. Generations of Bharatiya students were taught that their country was divided along racial lines from its very inception, with little room for alternative interpretations. This has had a profoundly negative impact on Bharatiya society, fostering a sense of division and alienation that has persisted into the present day.

Reclaiming Bharat’s Civilisational Unity

Despite the efforts of leftist historians to divide Bharat along racial and regional lines, the idea of Akhand Bharat remains a powerful force in Bharatiya’s consciousness. The concept of a united Bharat, bound together by shared cultural, spiritual, and historical ties, is not a mere political slogan but a reflection of Bharat’s civilisational ethos. The notion of Akhand Bharat can be traced back to ancient Hindu philosophy, which speaks of Bharatvarsha as a sacred land stretching from the Himalayas to the southern seas. This concept is reflected in ancient texts like the Vishnu Purana, which describes the entire subcontinent as a single cultural and spiritual unit. For centuries, this idea of civilisational unity was reinforced through pilgrimage, trade, and cultural exchange, ensuring that even in political fragmentation, Bharat remained united at a deeper level. Today, it is more important than ever to reclaim and reinforce the idea of Akhand Bharat in the face of the divisive forces that threaten Bharat’s unity. The artificial constructs of the Aryan-Dravidian divide, fostered by leftist historians, must be dismantled, and replaced with a narrative that celebrates Bharat’s civilisational continuity. The reality is that Bharat, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, has always been bound by an underlying spiritual unity that transcends regional, linguistic, and even religious differences.

One of the key aspects of this civilisational unity is Sanatan Dharma, or the eternal tradition, which has shaped the ethos of Bharat n society for millennia. Sanatan Dharma is not confined to a single text, doctrine, or geographic region; it is a living tradition that has adapted and evolved while maintaining its core principles of dharma (righteousness), karma (action), and moksha (liberation). The Aryan-Dravidian narrative, with its emphasis on racial and ethnic divisions, ignores the fact that both northern and southern Bharat have contributed immensely to this shared spiritual heritage. Bharat’s religious and philosophical traditions have always been interconnected, from the Vedic sages of the north to the Shaiva and Vaishnava traditions of the south. This is not to say that Bharat has never experienced internal conflicts or regional differences. However, these differences have historically been overcome through dialogue, integration, and shared cultural practices, rather than through the rigid, conflict-driven narratives leftist historians have sought to impose. The Bhakti movement, for example, which flourished across Bharat from the 8th to the 17th centuries, transcended regional and caste boundaries, emphasising devotion to a personal god and the equality of all devotees. Saints like Ramanuja in the south and Kabir in the north preached messages of unity and love that resonated across linguistic and regional divides.

Way Forward

Thus, the narrative of the Aryan-Dravidian divide, perpetuated by leftist historians, has been one of the most damaging falsehoods imposed on the Bharatiya consciousness. It is a narrative that has sought to fracture the unity of Akhand Bharat, undermine the civilisational continuity of Bharat, and weaken the spiritual and cultural bonds that have held this ancient land together for millennia. Leftist historians, driven by Marxist ideology and political motivations, have deliberately distorted Bharat’s history, presenting a false picture of racial and ethnic conflict where none existed. This narrative has not only divided northern and southern Bharat but has also been used to fuel regionalism, separatism, and communal tensions, undermining the unity of the nation.

However, modern scientific research, archaeological discoveries, and the resurgence of interest in Bharat’s classical heritage have all contributed to debunking the Aryan Invasion Theory and restoring the true narrative of Bharat’s civilisational unity. The idea of Akhand Bharat, which has been at the heart of Hindu philosophy for centuries, is not just a political slogan but a reflection of the deep spiritual and cultural continuity that binds the people of this land together. As Bharat moves forward, it is essential to reclaim this narrative, restore the unity of Akhand Bharat, and reject the divisive ideologies that have sought to weaken the nation. Through educational reform, cultural revival, and public engagement with Bharat’s ancient heritage, the people of Bharat can once again embrace their shared identity and move toward a future of unity, strength, and national integrity. The dream of Akhand Bharat is not a distant or impossible goal. It is the realisation of Bharat’s true civilisational potential, a vision of a united and prosperous nation that celebrates its diversity while remaining anchored in the timeless values of Sanatan Dharma. The time has come to move beyond the false narratives of the past and embrace the truth of Bharat’s ancient unity—one nation, one people, and one civilisation.

Comments