Since the announcement of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, the Congress party, under the leadership of Rahul Gandhi, has placed the ‘Caste Census’ at the heart of its campaign, rallying behind the slogan, “Jitni Abadi, Utna Haq” (As much population, so much right). This message is intended to present the Congress as the unwavering champion of the backward classes and Dalits. They have gone to great lengths in this effort—questioning everyone from the Prime Minister to journalists on the streets about their caste, scrutinising Dalit representation in key appointments, and even raising concerns over Dalit inclusion in beauty pageants.

The Congress seems intent on pushing a narrative that they are the last standing advocate for the rights of Dalits and backward communities in Bharat.

However, this raises a critical question: Is Congress truly the messiah it claims to be, or is this just an election strategy designed to garner votes from these communities? Their historical record, political actions, and actual engagement with the backward classes come under scrutiny when juxtaposed against this newfound vigour. While the rhetoric is powerful, it is important to ask whether their promises translate into lasting change, or if this is merely a tactical move ahead of elections.

To explore this question, Organiser delves into the stories of Dalit atrocities in Haryana, where a legacy of caste-based violence and abandonment under Congress rule still haunts the state. From gang rapes to systemic discrimination, the promises of justice have remained unfulfilled, leaving many wondering if Congress’s rhetoric matches its actions.

To begin with, let me share a heartbreaking story—a family from the Chamar community whose daughter had been brutally gang-raped by eight men in 2012, during the time when Bhupinder Singh Hooda, a Congress leader, was the Chief Minister of the state.

The village, once a witness to such an unspeakable crime, now seems to have moved on. No one openly discusses the case, and the villagers, when asked, simply say that things are better now. But the echoes of what happened to that young girl linger in the air.

“Tab to Congress ki hi Sarkar thi….”

On September 29, Organiser visited Dabra village in Haryana’s Hisar district, where the crime took place. The daughter of Raju Chamar, now dead, was brutally raped by eight men back in 2012. The crime occurred in the fields of Pawan Kumar, who lives near the house of the village Sarpanch. Recalling the incident, Pawan told Organiser, “It was a brutal case. The girl’s father, unable to bear the shame, committed suicide. But the cruel irony is that all eight accused, sons of powerful landowners, are now free and roam the village. Meanwhile, the Chamar family had no choice but to leave.”

Pawan identified all the accused as: Vikas Dudi, Baljit Mil, Raj Kumar, Pawan Deonda, Anil Siag, Mahender, Kuldeep, and Sunil. He directed us to the Dalit basti, where the victim’s family used to live. It was about 1.5 kilometres from the Sarpanch’s house, who wasn’t home during our visit.

As we entered the basti, a handicapped man in his sixties, named Balvant, pointed us towards the gali (street) where the victim’s family once lived. He asked a passerby to guide us to “Raju Chamar’s” house, though they had since moved elsewhere. A young woman opened the door and, though she didn’t recall much about the case, generously invited us inside as the heat outside was oppressive. She rushed to her mother-in-law, saying that some visitors from Delhi were inquiring about an old case.

Vimla, the mother-in-law, slowly rose from her charpoy lying under a neem tree. “It was a terrible day, madam,” she began. “Who could have imagined something like this would happen? But it did, and our family was shattered. Ashamed and broken. Back then, things were different. We couldn’t even speak up. People came, threatening us not to file a case. But we were adamant. We wanted justice. Now, years have passed, and I have lost touch with them. Why are you asking about this now?”

When we asked about the status of the case, Vimla sighed, “All of them are free now.” We spoke for over an hour about their lives since 2012, how the village had changed, and what the future held. On the topic of elections, she remarked, “Madam, when this happened to our daughter, wasn’t the Congress government in power?” She acknowledged that the Hooda administration provided compensation and booked the accused, but her voice still carried the same painful question: “Why did this happen to a Dalit girl?”

Vimla showed us her home, explaining that the only remnant from that tragic time was the neem tree she sat under. The rest of the house had been renovated. As for the girl, she quietly said, “She now lives in Hisar. I can’t share more than that.”

We later moved to a nearby chopal (village square) where men were playing cards. While discussing the upcoming elections, we encountered the brother of Anil Siag, one of the accused. He bluntly stated, “I managed to get my brother out….” He then shockingly added, “Madam ji, the girl wasn’t innocent either… she had an affair with a boy. She used to laugh and talk with him.” Realising that this correspondent was covering the case, he quickly stopped talking.

No mention of the caste of the accused in the whole case

According to available reports, on September 9, 2012, the girl was on her way to visit a relative in a nearby village when she was abducted by a group of 8 to 12 men. They raped her and filmed the heinous act. The victim later testified that 12 men were involved, though four of them were never named in the FIR or media reports. She believed the police intentionally excluded those names to shield them. Allegedly, seven men raped her while five others stood guard.

The men dragged her to a field, forced her to consume some pills, and then carried out the assault. They recorded the crime and threatened to release the footage if she told anyone. Silenced by fear, she kept quiet. However, the men eventually began selling the video for as little as 200 rupees. When her father learned about the video, he was devastated and took his own life by consuming pesticides.

It was only after her father’s tragic suicide that the case garnered attention. Local activists protested, and the police were finally forced to act. By that time, the accused had already fled. The investigation was marred by delays, and the victim and her family faced continuous harassment. The police, under Congress, would pick up random men, asking her to identify them as the rapists. When she couldn’t, they taunted her with remarks like, “If this isn’t the guy, then find them yourself.”

Shockingly, the caste of the perpetrators was deliberately omitted from the police reports, and instead, they attempted to implicate Dalit youths, including the victim’s own brother.

Today, the case remains a painful chapter in the lives of those affected, and it serves as a stark reminder of the deep-rooted injustice and political apathy faced by marginalised communities. The Congress party, which claims to be the champion of Dalit rights, has yet to answer why such horrors continue to occur under its watch. For the family of that young girl, justice remains elusive, and the scars of 2012 are far from healed.

The case, and particularly meeting the family, was profoundly disturbing, prompting us to investigate further and track down similar cases. To our shock, there were numerous incidents just like this one.

Congress did Pakshpat

About 14 kilometres from Dabra lies Bhagana village, where hundreds of Dalit families were forced to abandon their homes due to social boycott.

The conflict began in 2011 when a panchayat committee was formed to redistribute land among Dalits and the villagers. However, the Dalits allege that the committee was composed solely of dominant castes, who then monopolised the land redistribution. A historically significant spot known as “Chamar Chowk,” used for Dalit gatherings for generations, was handed over to the villagers. Tensions further escalated in 2012 when the Bhagana panchayat allotted 280 acres of common land under the Mahatma Gandhi Grameen Basti Yojana, which was meant to benefit families living below the poverty line (BPL) as per a 2011 state government announcement.

However, the promised land allotment never materialised for the Dalits. Instead, the panchayat took matters into its own hands. The Sarpanch and other panchayat members devised a scheme to distribute the common land. Upper-caste families were each given 1,000 square yards of land, while Dalit families—most of whom were landless—were allocated just 100 square yards. Adding insult to injury, the Dalits were also asked to pay Rs 1,000 as a registration fee. The result was that the upper caste people managed to claim the majority of the land.

Vikram Valmiki, one of the victims who recently returned to Bhagana, shared his experience with Organiser. He recalled that while the dispute was ongoing, the Congress government under Bhupinder Singh Hooda, along with local MLA Ram Niwas Ghorela, turned a blind eye to their plight. “They did ‘Pakshpath,’” Vikram said, explaining that instead of addressing their concerns, the police jailed Dalits, including his own brother and sister.

“We had no choice but to leave the village,” Vikram continued. “We were barred from buying rations, the shops refused to serve us, our children couldn’t play, and no one offered us work. We were forced to live hand-to-mouth, and eventually, we had to flee.”

The situation was dire. A committee was formed by the Dalit community to plead their case before the then Chief Minister, Bhupinder Hooda. However, their cries for justice were ignored, and Hooda told them, “You people have no right to that land.”

Activists at the time were quoted saying that when they approached Hooda, he unapologetically declared, “I am a Jat first, and a CM later,” dismissing the Dalit community’s grievances.

Vikram’s memories of those days are filled with pain and bitterness. “We had to leave our homes, and wander wherever we could find a livelihood. If not, we faced constant harassment. I was even attacked. When I filed a case under the SC-ST Act, they retaliated by accusing me of harassing their wives. This was the state of affairs.”

Life became unbearable for the Dalit families. “Our children had to walk past upper caste-dominated streets to get to school, facing threats every day. How could we survive there?” Vikram asked. As a result, many families relocated to other areas like Gohana and Dandoor. To this day, Bhagana remains a village of empty homes, with only a few Dalit families returning.

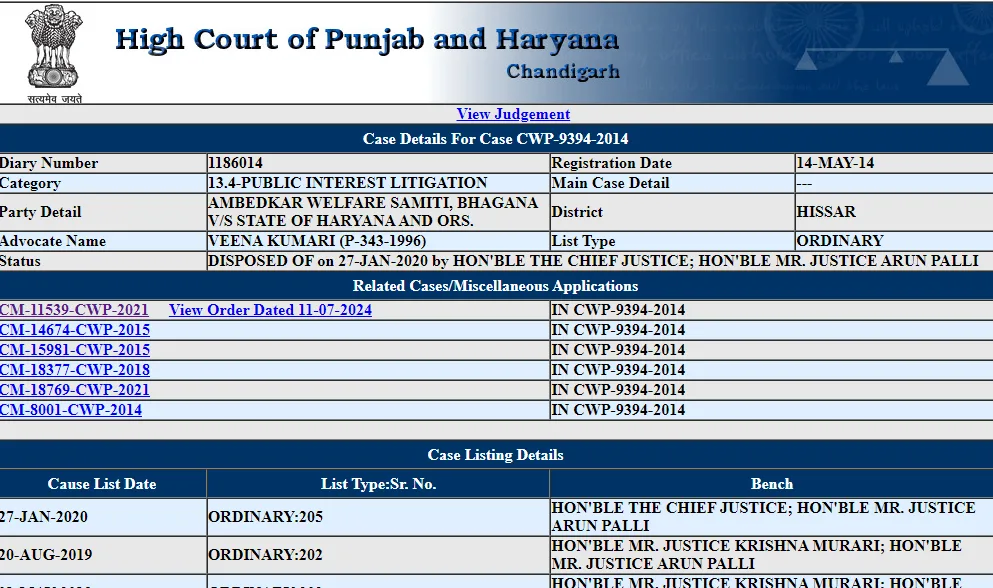

In total, 138 Dalit families were driven from Bhagana, unable to cope with the systematic discrimination. A legal battle over the encroachment of common land by the upper caste is still ongoing in the Haryana High Court, with 233 Dalit families involved in the case. The next hearing is scheduled for October 28, under (case number 11539-CWP) as accessed by Organiser, between Ambedkar Welfare Samiti and the State of Haryana.

“Hooda supported the attackers..”

To follow yet another case of caste violence, we travelled nearly 50 kilometres to reach the village of Mirchpur, where a devastating incident known as the ‘Mirchpur Burning’ took place. The tragic event unfolded on April 21, 2010, when a 70-year-old man named Tara Chand and his 17-year-old daughter Suman, who was physically disabled due to polio, were burned alive in a brutal attack. A mob of over 100 upper-caste men torched their home and 18 other houses in the Balmiki Dalit colony, forcing 258 Dalit families to flee the village.

Jogendra Valmiki, one of the survivors Organiser met, vividly recalled the horrors of that day. “On April 21, 2010, thousands of people surrounded our homes. The SHO of Narnond, Vinod Kajal, was there, and everything was orchestrated by Hooda. He gave us just an hour to leave our houses before the attack began. For three long hours, they rampaged through our colony, well-prepared, and armed. The government was on their side—imagine our helplessness,” he said, his voice filled with both pain and indignation.

The reason for the attack? Jogendra explained it with a deep sigh, “It was the education of Dalits, the improvement in our living standards, and the sense of equality that infuriated them. They couldn’t bear to see us rise.” He described how the mob charged at them, setting fire to their homes, with Tara Chand and his disabled daughter caught in the flames. “The smoke was so thick, it felt like a coal-powered train was passing through our village. We all ran—men, women, children—some barefoot, others without clothes,” he continued, his eyes reflecting the trauma that time has failed to heal.

When asked if any help came from the Congress government at the time, Jogendra’s voice turned bitter. “They didn’t care. Hooda rebuilt the 18 burned houses but took no action against the attackers. We had no choice but to leave; how could we return to face further abuse?” He questioned the sincerity of the government’s efforts, adding, “It was only after Manohar Lal Khattar’s government came to power that we felt any semblance of security.”

The legal battle that followed was equally painful for the Dalit community. In 2011, the trial court convicted 15 members of the upper caste community, while 82 others were acquitted. Seven years later, in 2018, the Delhi High Court upheld 13 convictions and overturned the acquittal of 20 others, bringing the total number of convictions to 33. The High Court observed, “After 71 years of independence, atrocities against Scheduled Castes by dominant castes have not subsided.”

Rehabilitation efforts

The Haryana government allocated Rs 4.56 crore for the rehabilitation of the displaced Dalit families. In 2020, Krishan Bedi, the political secretary to Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar, distributed possession letters for plots to 102 Dalit families in a new colony named Deendayal Puram.

Other families, like that of Saroj Devi’s husband, still live with the memories of the violence. “We spent years running from place to place for survival. Now that the government has given us houses, can we ever get back our past? No, never. How can we trust Congress after what they allowed to happen?” he asked, his voice heavy with disbelief.

We visited the 18 houses rebuilt after the fire and found not a single original resident there. The homes had been rented out to new tenants, while their rightful owners never returned.

The Daulatpur case

In a heartbreaking similarity, another case of caste violence occurred in 2012 in Daulatpur village of Haryana’s Uklana region. Rajesh, a Dalit man working as a contract labourer, had his hand severed by an upper-caste man named Pappu for the “crime” of drinking water from an earthen pot belonging to the latter. The brutality of such caste-based atrocities continues to shock the conscience, reminding us of the deep-rooted caste divides that still plague Indian society.

Is Congress the real Messiah?

As I wrap up this story, it’s impossible to ignore the recurring accusations that Congress has often sided with the oppressors in cases of atrocities against Dalits. And yet, Rahul Gandhi audaciously presents himself as the “Messiah” of Dalits, all while indulging in endless rhetoric about caste (“Jaati Jaati”). But where is the action to back up his words?

When I asked Jogendra from Mirchpur about this, I mentioned how Rahul Gandhi talks incessantly about the caste census and had even spread fear during the Lok Sabha elections, claiming that if the BJP were to come to power, they would change the Constitution. I asked how much trust Jogendra places in Rahul Gandhi. His response was sharp and unwavering: “Madam, Rahul Gandhi himself is nothing but a ‘jumla.’ We don’t trust him at all.”

The hypocrisy is glaring. How can someone who claims to champion the cause of Dalits be part of a legacy that has, time and again, abandoned them when they needed justice the most? Rahul Gandhi’s words ring hollow in the face of the lived experiences of Dalits like Jogendra, who know all too well the pain of betrayal.

Comments