The role of municipalities holds the key to determining the state of urban experience. A decentralised power structure in which a municipal body can function autonomously is deemed to be essential for a robust urban policy and governance framework. The Constitution (74th Amendment) Act of 1992 of India was enacted to provide more autonomy to the urban local bodies (ULB) by transferring 18 critical functions from the state government to ULBs.

However, the challenges of limited functional and financial power remain largely unaddressed. Municipal elections have been also irregular on multiple instances. For example, one of India’s most urbanised states, Maharashtra has been functioning without elected municipal boards since 2020, owing to unresolved issues about the representation of the Other Backward Class (OBC) in ULBs.

At this juncture, it might bode well to look into the history of municipal governance in India, which commenced during the British colonial era. The first municipal corporation was set up in Chennai (erstwhile Madras) in 1688, and then municipal corporations were established in Mumbai (erstwhile Bombay) and Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta) by 1726. While the country was ruled by the British, the municipalities became one of the initial bodies where Indians were able to practice self-governance through an electoral system.

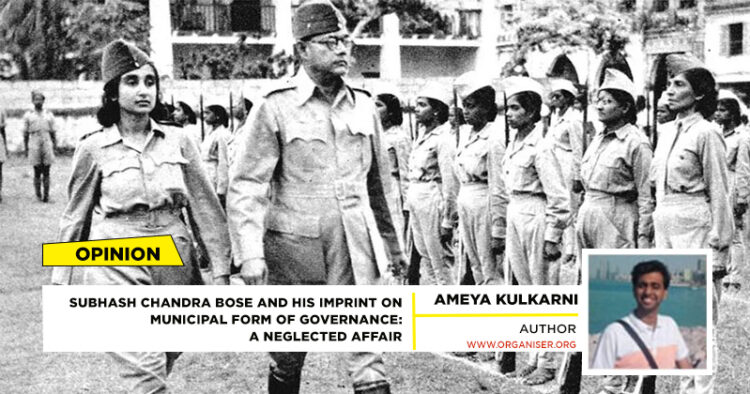

The functioning of the municipalities, headed by Indians, was not a smooth affair, as the nationalistic objectives of the Indian leaders often collided with the repressive antics of the British government. Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, India’s foremost freedom fighter, was the mayor of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) from 1930-1931. A close examination of Netaji’s mayoral tenure reveals the challenges of working towards peoples’ welfare while being subjected to an unequal power structure perpetuated by British colonial rule.

Similar experiences of Indian nationalist leaders in other governing bodies during a similar time frame could be instructive for today’s governance and policy challenges. A key contribution of Subhash Bose at KMC was the commissioning of the municipal gazette, which was conceptualised to be a link between the people and KMC’s affairs. The first gazette was published on 1 April 1924. The gazettes, along with other municipal governance-centric materials, are now digitally archived by the KMC and they are the main data sources of this article.

Bose’s Endeavours in Municipal Governance

Subhash Bose’s tenure at the KMC began in 1924 as a councillor and concluded in 1940 as an alderman. He was introduced to the municipality through his political mentor Deshhbandhu Chittaranjan Das, who was a lawyer of the highest order and a beacon of the anti-colonial Swadeshi Movement.

Chittaranjan Das was elected as the mayor of KMC and Subhash Bose was the chief executive officer (CEO), who supervised the status of the corporation’s deliverables. Some of the focus areas of the KMC under Chittaranjan Das’s leadership were—free primary education; free medical services to the poor; supply of good-quality food and milk; improvement in the supply of filtered and unfiltered water, better sanitation; housing for the poor, development of suburban areas; improved transport facilities; and greater efficiency in administration at a cheaper cost. As the CEO, and later as a mayor, Bose advanced these agendas while managing to expand the sphere of municipal governance.

The issue of people’s livelihood and labour welfare was also emphasized under Bose’s tenure. As a mayor of KMC, he supported initiatives of the Bengal Bus Syndicate (a body formed by Indian bus owners), to compete with the British government-backed Tramways Company. He did so by arranging permits for new routes for buses under the Bengal Bus Syndicate.

Bose publicly stated his objections to monopoly practice and advocated locally made products in manufacturing endeavours. Through civic duties and responsibilities, Bose envisaged a national development discourse which would serve as a worthy alternative to British rule.

The patronage system was a common practice during the British administration, wherein staff were recruited by governing agencies on the recommendations of existing employees. Bose flagged the issues with such a patronage system and pointed out that such a system can only operate through an inherent power asymmetry.

Instead, Bose lobbied strongly for a competitive appointment system (much like the system in place for selecting Indian Civil Service officers). Unfortunately, the recruitment of workers in municipalities and other public institutions in India remains plagued with allegations of corruption even today, which stifles the efficient delivery of public service and welfare. Towards, having skilled municipal workers, Bose proposed Calcutta University to open a sub-department for teaching municipal governance, under the political science department.

In today’s world, there is a growing recognition and need for diversity, equity and inclusive (DEI) in the workplace across the professional sectors. In that regard, Subhash Bose was a visionary, far ahead of his times, as he strongly advocated for proportional representation of minorities in the KMC workforce.

Even during the strained relationship between the Indian National Congress and the Indian Muslim League, Bose was able to forge an alliance between the two groups and worked with prominent Muslim leaders. While his immensely popular stature as a nationalist leader took him to different parts of the country, Bose’s experience as an administrator was also sought after in different municipalities across India. Archival material reveals that Bose was frequently invited to municipalities such as Karachi (currently in Pakistan) and Kushtea (currently in Bangladesh), where he largely stressed on the importance of local self-government institutions.

On one hand, Bose was aware of India’s traditional governance mechanisms, on the other hand, he had a sharp insight about the issues of municipal governance in other countries. Bose was on the lookout for lessons of municipal governance elsewhere and applying it in Kolkata. Once, he asked a KMC official to get in touch with the London County Council to obtain more information on how a network of cold storages can be developed in Kolkata to reduce food wastage.

Conclusion

Subhash Bose was a far-thinking administrator, which was evident through his functioning in the KMC. He was aware of the power asymmetries and imbalance while striving towards a model of governance that India could claim as its own. The empowerment of the KMC through the mayor-in-council governing system was consolidated during Bose’s tenure at KMC and it stood out as a pioneering exercise. Even today, many major municipal corporations, like Mumbai, are yet to have a democratically elected mayor and other council members.

Bose envisaged an expansive role of the municipality in terms of providing service to people by focusing on education, health, food supply, and transport while being aware of the planning required for the city’s expansion. In contrast, today’s municipal bodies in India, seem to have very little leverage in shaping the urban landscape, while being constrained by the lack of funds due to diminishing scopes of tax revenues. Bose was ambitious in terms of providing the best service to the people through KMC and he was aware of all the lessons that could learnt from other Indian municipalities like Delhi, Mumbai, and Chittagong. He was quick to understand the needs of foreign expertise, such as in the domains of river engineering and road technology.

While Subhash was immensely popular for his political activism and role as a mayor, his tenure at the KMC was frequently disrupted as he was arrested by the British administration. In fact, archival materials reveal that the British administration was alarmed at the election of Subhash Bose as mayor given his unwavering commitment to India’s independence. Eventually, Bose decided to step down from the position of mayor and continue with his public life outside the KMC. Nevertheless, Subhash Bose’s tenure at the KMC was marked by visionary thinking and proactive engagement, guided by dedication to people and the nation’s welfare.

The involvement of nationalistic leaders in urban municipal governance during the British period shows the importance accorded to city administration by the political class. In addition to Subhash Bose, some of the other notable leaders involved in municipal governance under British rule were Gopal Krishna Gokhale (Pune), Surendranath Banerjee (Kolkata), Aruna Asaf Ali (Delhi) and Vithalbhai Patel and Phiorzshah Mehta (Mumbai).

As this article shows, Bose’s adroit administrative skills, achieved significant goals despite functioning under a hostile colonial government. A re-engagement with this illustrious history of urban governance during challenging times, might offer the right motivation across the socio-political spectrum to give due importance and attention to municipal affairs in India.

Comments