A recent report submitted by the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi (EAC-PM), has shed light on significant demographic shifts in India and its neighbouring countries between 1950 and 2015. According to this report titled “Share of Religious Minorities – A Cross-Country Analysis (1950-2015),” co-authored by Shamika Ravi, Abraham Jose, and Apurv Kumar Mishra, the Hindu population in India experienced a notable decline of 7.8 per cent during this period, contrasting sharply with the growth rates of other religious communities.

The study underscores that while Hindus constituted 84 per cent of India’s population in 1950, by 2015, their share had decreased to 78 per cent. In contrast, the Muslim population in India witnessed a significant increase, rising from 9.84 per cent in 1950 to 14.09 per cent in 2015.

These trends are not isolated to India but are reflective of broader global patterns. Across 167 countries where a religious group holds a majority, demographic shifts have been observed. However, India’s demographic trajectory differs markedly from that of its immediate neighbours.

Despite being the majority community in India, Hindus experienced a decline of 7.8 per cent over the 65-year period under study. Conversely, in neighbouring countries where Muslims comprise a majority, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, there was a notable increase in the Muslim population’s share within the overall demographic mix. Bangladesh, for instance, witnessed the most substantial increase at 18.5 per cent, followed by Pakistan at 3.75 per cent and Afghanistan at 0.29 per cent.

The report also delves into Pakistan’s demographic landscape, noting a 3.75 per cent increase in the share of the majority religious denomination, Hanafi Muslims. Despite the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, Pakistan saw a significant 10 per cent rise in the total Muslim population, with Hanafi Muslims constituting the majority identity.

However, India’s experience contrasts starkly with these trends. The decline of Hindus by 7.8 per cent represents the second most significant decrease in the immediate neighbourhood, trailing only behind Myanmar’s decline of 10 per cent. Myanmar, in fact, witnessed the most substantial decline in the majority community’s share within the country’s overall population.

This report underscores the complex demographic dynamics at play in the region and the need for nuanced analysis to understand the factors driving these shifts over time.

Over the span of 65 years, Myanmar witnessed a significant decline of 10 per cent in its majority population of Theravada Buddhists. Similarly, Nepal, akin to India, experienced a 3.6 per cent decrease in the share of its Hindu majority within the national population.

India’s neighbouring countries with a predominantly Buddhist population, Bhutan and Sri Lanka, saw contrasting trends. Bhutan recorded a notable increase of 17.6 per cent, while Sri Lanka saw a more modest rise of 5.25 per cent. However, in the Maldives, the share of the dominant group, Shafi’i Sunnis, decreased by 1.47 per cent, according to the study conducted by the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PM’s EAC).

The study highlighted that a diminishing majority, indicated by a negative rate of change in the majority population’s share (coupled with a rise in the minority population’s share) from 1950 to 2015, suggests a conducive environment for enhancing diversity in the country.

Contrary to certain narratives, the study emphasised that minorities in India are not only protected but are thriving. This stands out in the South Asian context, where the share of majority religious denominations has expanded, while minority populations have diminished notably in countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Afghanistan.

The study attributed this trend to a combination of policy measures, political decisions, and societal processes that foster diversity in Indian society. It lauded India for its progressive policies and inclusive institutions, highlighting the legal definition of minorities and the constitutionally protected rights afforded to them. As a result, India has seen a growing number of minority populations within its borders.

This conducive environment has made India a favoured nation for persecuted minorities in neighbouring countries, who often seek refuge within its borders during times of adversity.

The statement underscores, “It comes as no surprise, then, that minority populations from neighbouring regions seek refuge in India during times of adversity. Over the past six decades, India has provided a nurturing haven for Tibetan Buddhists fleeing persecution in China, offering them a comfortable home. Similarly, the Matuas, escaping religious persecution in Bangladesh, have found a place within Indian society and have been assimilated seamlessly. Moreover, India is home to a significant population of refugees from Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Afghanistan. Upholding its pluralistic, liberal, and democratic values, India continues its longstanding civilisational tradition of sheltering persecuted populations from various countries.”

The study asserts that India’s demographic evolution aligns with broader global trends, reflecting an increasing heterogeneity worldwide over the past six decades. In 1950, the majority population in societies comprised 75 per cent, yet by 2015, the share of the majority religion in countries worldwide had decreased by 22 per cent.

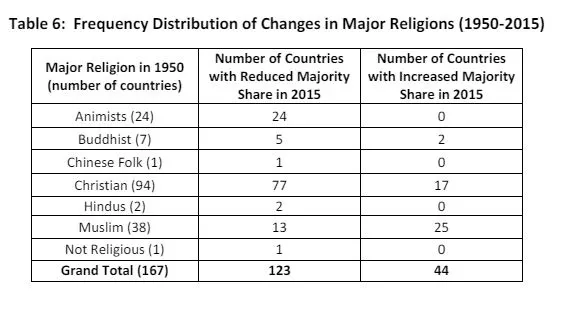

According to the study, 123 countries witnessed a decline in the share of the majority religious group, while its prevalence increased in 44 countries. This change ranged from a drastic 99 per cent decrease in Liberia to a substantial 80 per cent increase in Namibia.

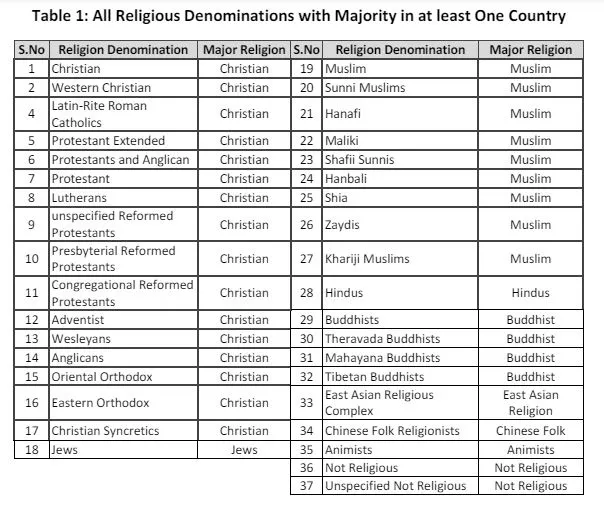

Further analysis reveals that sixteen distinct subcategories of Christianity constitute a majority in at least one country, alongside eight subcategories of Islam and three denominations of Buddhism. These findings illustrate the diverse religious landscapes shaping societies across the globe.

In 1950, animism was identified as the predominant religion in 24 countries, according to the RCS-Dem Dataset. However, by 2015, it ceased to hold majority status in any of them. Among the 94 countries where Christianity was the majority religion in 1950, 77 witnessed a decline in its share within the overall population mix. Conversely, during the same period, 25 out of the 38 countries with a Muslim majority experienced an increase in the share of their dominant religion. Notably, only two countries have a Hindu majority, and in both cases, their share of the population has decreased over the past 65 years.

Across most continents, more countries observed a decline in the dominance of the main religious group than an increase. Africa witnessed the most significant demographic shift, with 21 out of 40 countries undergoing substantial changes. Among the 35 high-income OECD nations, the decline in the dominance of the main religion was even higher at 29 per cent, compared to the global average of 22%.

The study highlights a significant gap in academic research on the relationship between religion and outcomes within and between states, attributing it to the lack of credible, granular, and timely datasets on religious demographics worldwide. This underscores the necessity for comprehensive studies like the one conducted, which meticulously analyse the changing demographic landscape globally and categorise the majority community with precision.

The study, undertaken by PM-EAC, draws on demographic data from the RCS-Dem dataset by ARDA, published in 2019. It contends that RCS-Dem offers more comprehensive and consistent religious demographic data compared to other sources such as WRD, WRP, and the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Studies. RCS-Dem records population figures for 97 religious denominations from the early 1800s onward, providing a valuable resource for understanding long-term demographic trends.

Comments