During one of his addresses in the Lok Sabha, Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighted the divisive nature of the Congress, accusing them of being entrenched in a ‘culture of cancellation’. He emphasised the stark contrast between their vision for progress, such as initiatives like Make in India, Aatmanirbhar Bharat, and Vocal for Local, and the Congress’ reflexive tendency to oppose and obstruct at every turn. Modi lamented the prevalence of such negativity, questioning how long such animosity could persist when even the nation’s achievements are subject to cancellation.

Modi’s remarks find resonance in real-world incidents, as evidenced by the case of Karua village in Madhya Pradesh’s Morena district.

Here, a Congress representative stands accused of obstructing the implementation of crucial services provided under a central scheme for petty political gains. Despite the installation of taps in every household and the construction of water tanks months prior, locals decry the Congress MLA’s interference, alleging a deliberate hindrance to water supply under the Jal Jeevan Mission. The initial jubilation of tap water connections, considered as a Diwali gift from the government, swiftly gave way to disappointment as the water supply ceased within days.

This situation underscores a historical context: In 1985, under Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, the National Drinking Water Mission was launched with the promise of providing tap water connections within a half-kilometre radius of every home. Fast forward to 2019, during Narendra Modi’s second term as Prime Minister, the establishment of the Jal Shakti department and the allocation of a substantial 3.6 lakh crore fund for water-related issues signified a renewed commitment to addressing water scarcity. The ‘Har Ghar Jal’ scheme, a cornerstone of Modi’s governance, has achieved what was once deemed unattainable, with over 14 crore connections established nationwide.

The villagers in Karua opened to Organiser about how they have been kept away from development and other benefits just because they are not the traditional voters of the Congress party. The little development that appears in the region was done during the tenure of the BJP’s MLA, Rustam Singh. Currently, Dinesh Gurjar from the Congress Party represents the constituency. Before him, Rakesh Mavai and Raghuraj Singh Kansana from the Congress party served the constituency respectively.

The Ground visit

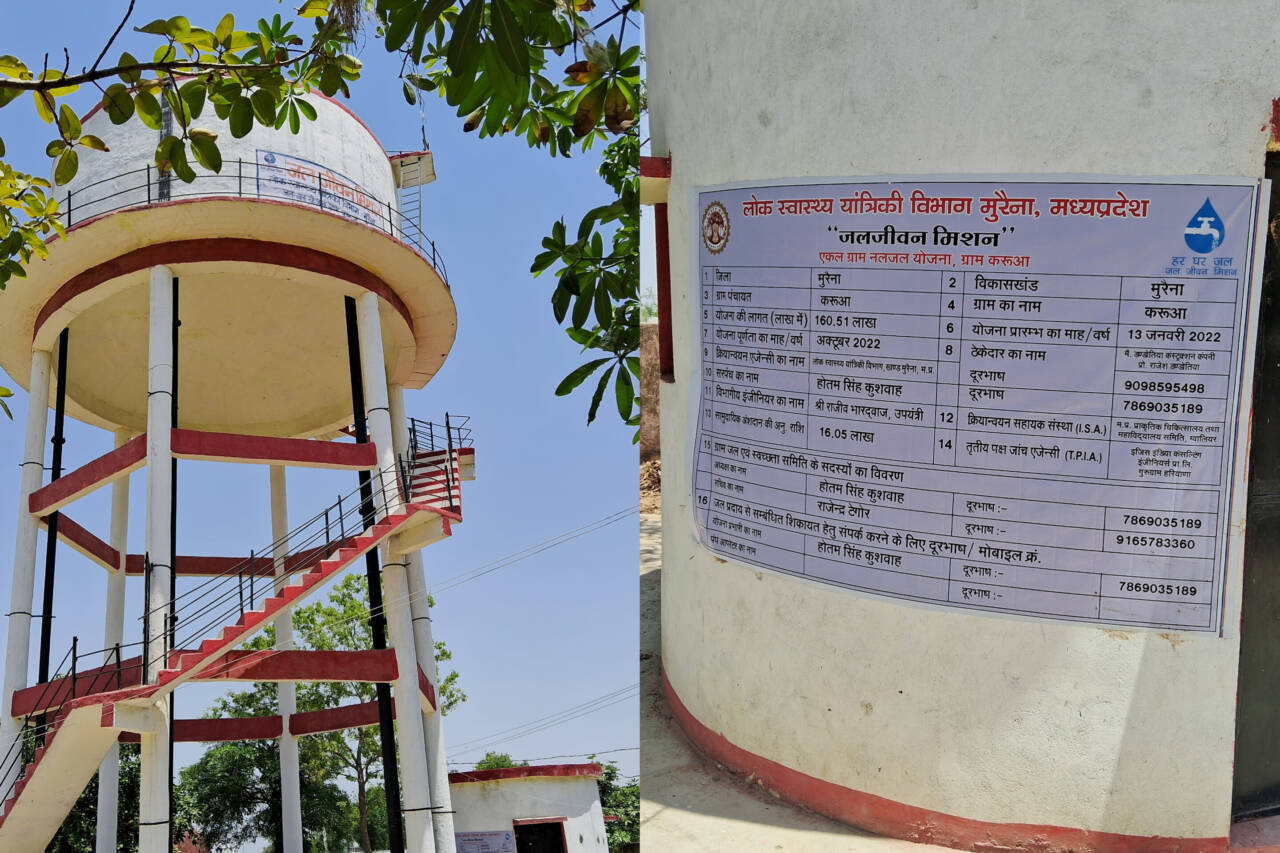

Karua, a village situated nearly ten kilometres from the bustling city of Morena, can be accessed via a narrow lane running parallel to the highway. Despite its distance, Karua seamlessly blends into the urban sprawl of Morena. Upon arrival, my attention was drawn to a water tank adorned with the slogans of the ‘Jal Jeevan Mission,’ signalling a significant development in the village: the provision of tap water connections. This water tank, situated within the premises of a primary school, welcomed me to Karua.

Adjacent to the school stood a building housing the local Anganwadi centre. As my vehicle traversed past the school, I sought directions to the residence of the village sarpanch from the friendly locals. This visit took place on April 25, 2024.

What followed was a startling sight: a rough, patchy road scattered with cow dung and various other waste strewn openly. Residents sat outside their homes and navigating through a narrow alley with sewage running through it, I reached the house of the Sarpanch. A group of about ten individuals, seated on charpais, promptly inquired about my presence, calling the Sarpanch.

Taps but no Water!

Their grievance was immediate: “Madam, there’s no water flowing from these taps. The government hasn’t provided any facilities,” they lamented. This revelation caught me off guard, contrary to my initial expectations.

Nearby, two children and their mothers gathered, waiting to collect water for household chores. Darshan Lal Kushwaha, an elderly resident, solemnly remarked, “This is the harsh reality, Madam. We’ve had water for a mere day or two from these taps, that’s all.”

Echoing his sentiments, the children chimed in, “Didi, the water tank was installed during Deepawali, and water flowed for just two days before the supply was cut off.”

Darshan Lal quickly interjected, “They claim it’s a technical fault, perhaps a damaged line somewhere.”

Soon, Uttam Singh Kushwaha, the Sarpanch, arrived. He revealed that despite 200–250 families having tap connections, there was no water supply. Moreover, electricity was accessed directly from the main wire as the distribution box remained unconnected.

Frustrated, Uttam Singh lamented, “I have pleaded with the MLA numerous times but to no avail. He promises action but never delivers.”

He urged me to explore the village firsthand to witness the dire conditions.

Meeting the villagers

Continuing on my journey, I was accompanied by kids from the village, along with a young man named Ravi Kushwaha in his twenties. Expressing his scepticism, Ravi questioned, “Madam, many like you have visited our village, yet nothing has changed. Will your visit make any difference?” I nodded, determined to make an effort.

Ravi guided me to the home of Prem Singh Kushwaha. His daughter, a school dropout, emerged and showed the water pipeline within their home, revealing its dry state. She had abandoned her studies in the fifth grade to assist her family with household chores, as the local school only extended to that level.

Next, we visited Shyamwati Kushwaha’s house, where she was engrossed in laundry. Despite a visible pipeline leading to the washing area, there was no tap attached. When questioned about her water source, she replied, “We fetch water from the Sarpanch’s house where you were seated, didi.”

Most households in the village relied on personal bore systems, utilising hand pumps when electricity was sporadic, which was often the case.

Ravi lamented, “Madam, the village’s condition is dire. Despite excelling in agriculture, they endure substandard living conditions. The government overlooks the ‘annadata‘ (provider of food), forgetting their plight.”

As we approached a crossroad, villagers emerged from their homes as a helicopter passed overhead, carrying PM Narendra Modi en route to a rally in Gwalior, 40 kilometres away. Children waved goodbye, shouting, “Bye Bye Modi Ji.”

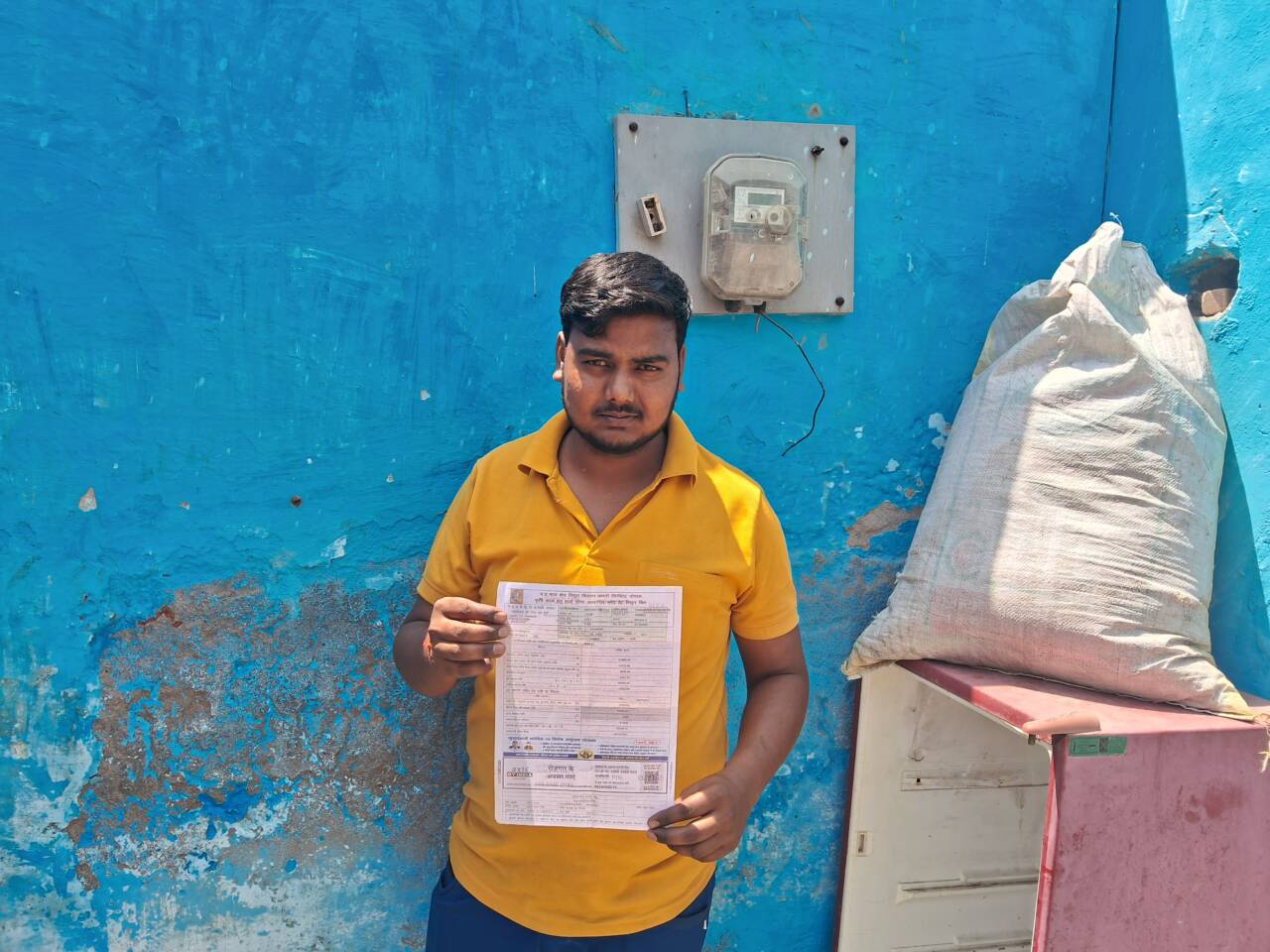

Continuing our tour, we visited Ram Babu’s house. Clad in a yellow t-shirt, he identified himself as a farmer. When asked about water, he pointed to the tap without water. He also highlighted exorbitant bills amounting to 60,000 rupees despite negligible electricity usage. He chuckled at the prospect of the electricity department disconnecting their line, quipping that they needed a connection first.

Ravi then led me to the other side of the village, where a water canal served irrigation purposes. Joyously, he opened the pipe of the tubewell, eliciting excitement from the children as they played with the water.

Reflecting on the village’s plight, Ravi remarked, “Our village faces myriad issues, from lack of essential amenities like schools, hospitals, and roads, to insufficient water and electricity supply. Families rely heavily on agriculture, often neglecting their children’s education, resulting in high dropout rates, particularly among girls.”

He continued, “The middle school is located in Tekri, about 5 kilometres from Karua. It’s situated in a village predominantly inhabited by Gurjars. We Kushwahas refrain from sending our daughters there due to potential disputes and harassment. Consequently, no Kushwaha daughter has progressed beyond the fifth grade.”

Caste politics further complicates matters. Karua is primarily a Kushwaha stronghold, traditionally supporting the BJP. However, the MLA hails from the Gurjar community, which constitutes the majority of the constituency. “Our caste’s representation in elections is minimal,” he lamented.

Ravi expressed his intent to vote for the BJP in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, citing Modi’s developmental initiatives and the perceived ineffectiveness of the Congress. He criticised the current MLA for obstructing development in the village, driven by personal and caste-based agendas. “We need a change, Madam,” he emphasised.

On my return journey, I encountered women and girls fetching water from a hand pump, all of whom had dropped out of school. When asked about their desires, Ram Sakhi articulated, “All we want is water, electricity, and better roads.”

It’s disheartening that despite the seemingly good condition of the water tank, there are still significant issues plaguing the village.

Jal Jeevan Mission

It’s important for readers to be aware that the Jal Jeevan Mission was a significant initiative launched by Prime Minister Modi on August 15, 2019. This initiative led to the establishment of the Jal Shakti Ministry. According to real-time data available on the website, as of August 15, 2019, approximately 3 crore families had access to water connections. As of May 2, 2024, this number had risen to 14 crore families.

Morena, situated on the border of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, faces challenges due to its arid landscape, with water from hand pumps often being brackish. Since the formation of the ministry, the state has witnessed a remarkable 60 per cent increase in water access.

Madhya Pradesh still has a long way to go in terms of providing tap water connections, but instances like one in Karua, where, despite infrastructure and supplies being in place, people still lack access to water, are deeply concerning. The politicisation of such issues only exacerbates the problem.

Organiser remains in contact with the villagers and will provide updates on any changes in the water supply situation in the coming future.

Comments