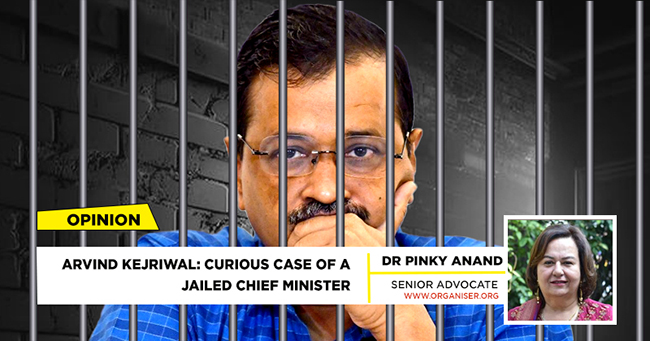

India, also known as Bharat, is a Union of States, and its federal functioning is vexed. A perusal of the recent events of the past would reveal such complexity. Yet within our federal structure and balance of powers and interests rest a stabilising instrument that constitutes one of the most robustly litigated provisions, i.e., Article 356 of the Constitution, “The failure of Constitutional Machinery” a question that has knocked the doors of the highest court of the land at times of extreme political pressure. The question has once again been raised with the recent remand of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal to judicial custody.

There exists a conflict of interests at this juncture; on the one side lies the oft-cited “innocent until proven guilty” principle, which would hold that stripping Mr Kejriwal of his power as Chief Minister would subject him to punishment before a conviction that flies in the face of the rule of law. On the other side lies the jurisprudential question of whether a State can adequately discharge its functions and guarantee to its citizens their fundamental rights and engage in representative administration; a denial of such a polity would be violative of the rule of Democracy. In that context, this Article has been framed to examine the questions that need to be settled with the latest turn of events. At the outset, I would like to clarify that this is not an article on the merits of the case against the Chief Minister but a mere examination of the moral and administrative case for the Chief Minister’s resignation.

For the record, this is not the first time a Chief Minister has been faced with the threat of prolonged incarceration midterm. Former Chief Minister of Bihar Lalu Prasad Yadav was charge-sheeted by the CBI for his role in the fodder scam; Former Karnataka Chief Minister B S Yediyurappa resigned in 2011 for indictment for illegally profiteering for land deals. Recently, the Former Chief Minister of Jharkhand, Hemant Soren, resigned midterm pending his imprisonment. However, this remains the only case wherein the Chief Minister has not resigned his position.

“The investigative agency is doing its work, I think we should let them do their work; everything is going to be apparent when things will come in court…I welcome this decision…” — Virendraa Sachdeva, BJP Delhi President

There is a tendency in our national discourse and at our own peril to grant the highest stamp of legitimacy to electoral democracy affirmed by a majority of our franchise-holders. In fact, electoral results are cited across forums as a form of affirmation that the people have sought to govern themselves through the sovereignty of such electoral bodies. A frequent case of supporters of the jailed Chief Minister cites the electoral legitimacy of the Chief Minister as the case to ensure that the will of persons is preserved.

Such a doctrine is true for the British; however, in the Indian polity, an alternative form of legitimacy runs parallel through our country’s Lex-Constitutional history, i.e., the authority of Constitutional Democracy. The Constitution serves as a document that our citizens have chosen to constitute themselves and to define and defend rights and structures that guarantee us equality, fraternity, and justice. It stands as a living document that is the collective will of we, the people. The Constitution in itself and the provisions of spirit and letter flowing therein are democratic in nature and capable in legitimacy and authority to prescribe the functioning of the rule of law within our society. It is from that very spirit that a moral and Constitutional case emerges for the Chief Minister to resign from office. It is indisputable that a Chief Minister behind bars stands without public trust nor the facilities to function in times of crisis and administrative need. Concerns regarding the ability of the State government to protect Fundamental rights, govern the Directive Principles of State Policy and function to preserve public interest and public trust form a pertinent query. For that very purpose, the drafters of the Constitution fashioned a sword to preserve such basic structure of our polity and Constitutional Democracy by handing the executive the powers to govern a State that has gone rogue.

“Arvind Kejriwal is a looter and corrupt but right now he is on the verge of mental bankruptcy. We accept what the court has said. If Arvind Kejriwal wants to call the court political, then this is his mental bankruptcy” — Manoj Tiwari, BJP MP

The President’s extraordinary powers under Article 356 have been subject to Constitution benches galore; the SR Bommai case laid out that such a power cannot be curtailed with ingredients but requires circumspection and careful application of mind. Such a power remains among the few Constitutional mandates that vest the duty to protect the Constitutional functions not to the judiciary as is under Articles 32, 142 and 226 but with the Executive. The question of what constitutes the failure of Constitutional machinery has been raised with every President’s rule. Still, it never has such a situation arisen wherein a sitting head of a state executive now operates out of jail. The question that the defenders of the Chief Minister speak from the pulpit of every newscast on air- is as to which provision of the Constitution is not being administered as a consequence of which the Hon’ble LG shall hold the state in emergency; the answer is very simple: it’s the entirety of the Constitution my Lord! The Constitution of India as a document rests on cooperative Democracy and the functioning of all branches of a nation’s polity both vertically and horizontally. The division of powers captured in the Seventh schedule is evidence of the importance of the State Government in advancing the endeavour of socio-economic advancement of its people. A Chief Minister behind bars, limited in practical sense by rules prescribed by the Delhi Jail Manual, cannot discharge their duties to ensure the administration of a state in accordance with the Constitution.

“I am very upset that Arvind Kejriwal, who used to work with me, raise his voice against liquor, is now making liquor policies. His arrest is because of his own deeds…” — Anna Hazare, Social activist

To illustrate: First, Rule 41 of Special Rules relating to Undertrial and Civil Prisoners provides that an unconvicted prisoner shall be granted facilities for writing two letters and two interviews each week with their relatives or friends. Second, the Rules further provide for confidential information only to be passed to the legal advisor of the prisoner, removing any facility where a Chief Minister handles sensitive and confidential information within the facilities and not violating the law. Third, Rule 33 of the Delhi Prisons (Discipline, Daily Routine, Offences and Punishments) Rules, 1988 list prohibited articles within the prison, including all books, paper and printed or written matter or appliances for printing or writing that the Superintendent of the police does not supply. Further, there is restrictions on typewriters and other recording instruments.

The old maxim propounded by Lord Acton had exclaimed, “Absolute power corrupts absolutely”; it was revised by John Steinback, who said, “Power does not corrupt. Fear corrupts… perhaps the fear of a loss of power.” These sayings ring true now. An anti-corruption crusader now behind bars is clinging on to his chair like how he once mocked his own enemies for holding on to. From “main Anna hun” to “Main hun Kejriwal” the AAP and its chief have come a full circle and become what they hate- A politician! A ruler with a shadow of a scam and a trial over his head cannot and does not inspire the confidence of the people to govern its city. Whilst Delhi sleeps without its Government, each day, the common man of Indian politics does the uncommon and holds unabashedly to his power. In a state that accounts for 29.04 per cent of the crimes against women reported in the 19 major cities and continues to log the most FIRs in metro cities, in a State with 29 million citizens, the Government is run by proxy from a prison. The moral and legal case for protection from a failed Constitution run by a noble custodian of his own interests is evident.

Comments