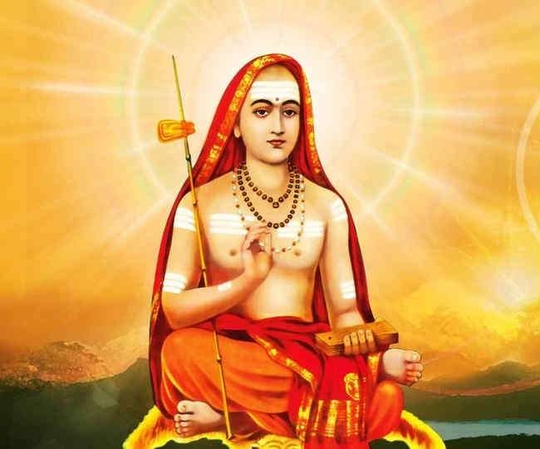

Adi Shankaracharya was not merely one person—in his persona, we find an expression of Bharat. Shankaracharya is best remembered for his remarkable spiritual and intellectual genius for his reinterpretations of Hindu scriptures and his scholarly thoughts on the Vedic canon, whether Brahma Sutras or principal Upanishads or Bhagavad Gita. His philosophical teachings have deeply influenced various sects of Hindu Dharma and also contributed to the development of the Akhand Bharat.

The significance of Shankaracharya (eighth-ninth century CE) in Indian history and spirituality can hardly be overstated. Living in the ninth century, what Shankaracharya brought about was truly monumental.

He founded four mathas or monasteries namely Sringeri Sharada Peetham, Dvaraka Pitha, Jyotirmatha Peetham and Govardhana Matha with the larger and long-lasting aim of establishing a geographical unity of India. Sri Adi Shankara Bhagavatpada consolidated his work by establishing in four directions, four Mathas called Amnaya Mathas to sustain and foster the sacred tradition of Sanatana Dharma. Keeping in mind that the Maths should serve as places of spiritual wisdom and peace for all seekers of the Truth, Sri Shankara chose spots bountiful with natural splendour and serenity. Sri Shankara chose Puri in the East and Dwaraka in the West, both being located on the shores of the sea. The Acharya also chose Badrinath in the North and Sringeri in the South for the natural aura that these places had, owing to the towering scenic mountains in both places.

Sri Shankara assigned one Veda for each of the Mathas, signifying that each Matha would play a significant role in taking efforts to sustain and propagate that particular Veda. Thus Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharvana Veda were assigned to Puri, Sringeri, Dwaraka and Badrinath Mutts respectively. Sri Shankara also nominated his four chief disciples, one to each of these Mathas. He assigned Sureshwara to Sringeri, Padmapada to Dwaraka, Hastamalaka to Puri and Totaka to Badri. The way all these Mathas function to this day shows the vigour of the movement started by Shankara for the propagation of Advaita Vedanta and Sanatana Dharma as a whole.

Regardless of which of the last two we consider to be the chief southern seat (both of them have been occupied by individuals of staggering spiritual stature, worthy of being in the lineage of the great teacher), it is clear that the vision Shankaracharya had for Bharat is particularly significant to us in two ways- this entire region, marked by these seats in which he installed a direct disciple each, constituted for him a single whole; and the essence of this whole was its spirituality. In line with this, he is also credited with organising the renunciates of the region into the dashanami order, which continues to this day.

Adi Shankaracharya has an unparalleled status in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta. He travelled all over India to help restore the study of the Vedas. His teachings and tradition form the basis of Smartism and have influenced Sant Mat lineages.

He introduced the Pañcāyatana form of worship, the simultaneous worship of five deities–Ganesha, Surya, Vishnu, Shiva and Devi. Shankara explained that all deities were but different forms of the one Brahman, the invisible Supreme Being.

Shankaracharya’s teachings and philosophy not only paved an impact on the people of Hinduism but at such a young age he had learnt all the Vedas, six Vedangas which itself is commendable. We can’t forget that his teaching methods of Vedas have contributed to the development of modern Hindu thought.

The intellectual achievement of Shankaracharya is truly staggering. He composed a lucid commentary on the Brahma-sutras, or the Vedanta-sutras, in which he articulated the identity of the atman with Brahman and referred extensively to the Upanishads as he did so. In addition, he composed commentaries on the Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita. At the same time, he is also credited with the composition of the Saundaryalahari, the Srividya text par excellence, which reveals the greatest mysteries of the cosmos to the initiated, and reads like a beautiful prayer to the uninitiated.

Just as significant, however, is the persistence of Shankaracharya in the everyday lives of people. Large portions of the hymns recited every day by numerous people in India (and the diaspora) are believed to have been composed by Shankaracharya. It reflects how people have understood Shankaracharya and how Bharat instinctively understands her own spirituality.

The simplicity with which the Atma-Shataka (the sextet on the atman) denies all identification with parts of the body, religious observance, even punya and paap, and declares Shivo’ham—I am Shiva—and the ease with which people continue to sing it, tells us something deeply significant about the spiritual attitudes and understanding in the country. It is not that each person who sings it is in that state of consciousness, or rather, has removed all her misidentifications; it means more that each of them knows this to be the Truth, which is to be unveiled for herself. At the same time, many of these hymns are deeply devotional, reminding us that the Indian way is not unitary but rather knows all these to be approached to the same reality.

Comments