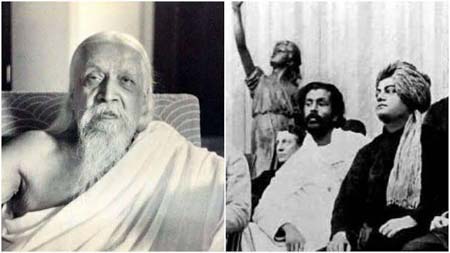

Legendary youth icon, Vivekanand throughout his short but strikingly inspirational and highly successful life kept emphasising the importance of decolonisation, most notably in his views on education and the way youth should embrace it for their own holistic development. Another iconic nationalist, a political genius of the rarest kind, sage Shri Aurobindo almost equally vehemently focused on the significance of educational and cultural decolonisation for attaining ‘swaraj’. Both of them in their own distinct ways insisted on imparting education in the native languages to ensure the growth of body, mind and soul. The ultimate objective of education for them both is to enable people develop, not just relevant skills to engage themselves with meaningful employment for economic progress, but also awaken their soul to integrate their body, mind and heart for spiritual enhancement and universal advancement. Both of these great minds recognised early on the value of Indian knowledge systems and their dissemination through the medium of mother tongues. Country reeling under the yoke of political subjugation of British and consequent cultural colonisation had surprisingly, though a pleasant one, gifted us these two beautiful minds who unequivocally and very much effectively advocated the need for decolonisation through the indigenous ways of knowledge creation, consumption and dissemination. Their main focus was to nurture youth in a manner to equip them get rid of colonial mindset. In their own times, despite the best attempts made by the likes of these noble and noteworthy souls, the decolonisation story succeeded relatively less.

Even in independent India, the process of decolonisation went slow since the centre of our education system kept revolving around the West and western language. The growth of nation remains stalled in ways more than one because of this continuing cultural colonisation. Therefore, a much deeper decolonisation of Indian mind, particularly young minds is absolutely indispensable for the growth of nation based upon a completely knowledge-centred economy for the sake of sustainable development along the lines of not only material prowess, but also spiritual accomplishment. Towards that end, National Education Policy (NEP) is an extremely important, rather a foundational document dealing as it does with making both ontological and epistemological shifts to decolonise Indian education system.

Seventy-five years down the line in independent India, we are still far behind being an economic and educational powerhouse we were in ancient times in an eco-friendly way for at least seventeen centuries as Angus Maddison rightly points out in his phenomenal work mapping the economic history of the world in which he categorically claims that Indian contribution to the global GDP was highest for these seventeen hundred years consecutively

Assumptions behind Macaulay Minutes of 1835 have been successfully supplanted. Macaulay moment was a culmination of an enduring debate between Orientalists and Anglicists for about a decade and a half. Orientalists were strongly in favour of continuing with the Indian education system the way it had been functioning since centuries. They underlined the incontrovertible fact that Indians did remarkably well with their existing, native educational model. Anglicists but forcefully argued for the introduction of English medium education, ostensibly to modernise but actually to produce “a class of Indians only in blood and colour but English in tastes, manners, morals and intellect” evidently for the sake of strengthening and perpetuating British Raj in India. For that purpose, they abandoned Indian texts and chose mostly western texts to teach them in English language. By repudiating colonial assumptions behind Macaulay’s English eduction policy, NEP makes certain paradigmatic departures as it puts its emphasis categorically on the inclusion of texts from Indian Knowledge Systems, and on the increasing use of Indian languages for teaching-learning and research purposes.

The radical restructuring of schooling systems, the inclusion of four-year undergraduate programme, the abolition of M.Phil, the provision of direct Ph.d after graduation with a specific focus on the rigour of reaserch and innovation, the promotion of entrepreneurship and culture of start-ups for enabling even school and college going students to be job creators rather than job seekers, and tremendous emphasis, as cited above, on the introduction of textual content from Indian intellectual traditions and on the development of adequate infrastructure and appropriate ambience to ensure that teaching-learning as well as research practices primarily take place in Indian languages tell us a promising story of nothing else but vociferously desired decolonisation which is a necessary prerequisite as India aspires to excel and grow rapidly in an ever increasingly globalised world with challenges of climate change and global warming connected with the threats of unsustainable development.

Seventy-five years down the line in independent India, we are still far behind being an economic and educational powerhouse we were in ancient times in an eco-friendly way for at least seventeen centuries as Angus Maddison rightly points out in his phenomenal work mapping the economic history of the world in which he categorically claims that Indian contribution to the global GDP was highest for these seventeen hundred years consecutively. This is to say that India was the richest country on earth from first to seventeen centuries AD.

The excellence of distinguished institutions like Nalanda and Takshashila, even before the existence of globally eminent universities like Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard and Stanford, for instances, along with the incredible skills and achievements of teachers like Chanakya offer us a remarkable saga of high academic standards and outstanding achievements. Colonial intervention systematically destroyed that indigenous culture of extraordinary practices by roping in an alien language as the medium of education and knowledge dissemination.

NEP categorically makes an attempt to neutralise the impact of that intervention, and it does so with a right vision as successfully identifying the talent of children and grooming them in their own areas of genuine interest are best possible when we allow and encourage them to express their minds and explore their creative urges in their mother tongues with easy access to both Indigenous and alien knowledge systems. Comparative approaches from school level onwards have the potential to persuade and motivate students orient themselves to look for relevant content and learn useful skills that can help them confidently deal with difficult circumstances and grow in real world situations. Schools are supposed to encourage students to pursue studies and teachers to teach them in the native languages. To fulfil that purpose, texts of all disciplines should be written in our own languages, and quality-oriented teacher-training centres be established to train teachers adequately to teach children properly.

Colleges in four-year undergraduate programme have laid enormous focus on innovation, start-ups, research and entrepreneurship. Chances of doing better in these areas will increase manifold if an academic climate is cultivated to effectively use our mother tongues for the above-mentioned purposes in higher studies. Answers, assignments, tests and theses should also be proactively encouraged to be written in mother tongues to generate an inspiring eco-system so as to promote the expression of ideas and thoughts in the native languages. It is pertinent to note that Indian Institute of Advanced Studies has already introduced the system in which fellows can write their papers and books in any of the twenty-two Indian languages as mentioned in the 8th schedule of Indian constitution. Decolonisation will certainly take place if our educational systems get redirected to Indian languages, texts and contexts.

Bharatiya Shikshan Mandal and Akhil Bhartiya Rashtriya Shaikshik Mahasangh since their respective inception have been making concerted efforts to reorient Indian education system to its indigenous roots. With unflinching commitment to the principle of conducting pedagogical practices in mother tongues, they are very uncompromising about imparting primary education to inculcate those values which will enable children evolve themselves physically, mentally, intellectually as well as spiritually. And they have been emphasizing the importance of cutting edge, quality research in the field of higher education to meet the challenges of contemporary times in a manner in which we are able to find a way out of the existing problems such as uneven development, ecological imbalance and a whole lot of other socio-political, cultural and economic issues. The primacy given to the research at per with global standards by both Mandal and Mahasangh is an extremely significant step to help India restore its rightfully glorious space in the world of letters.

Decolonisation stands for cultural confidence to impart education in our own ways to fulfil the interests and objectives of the generations of Indians including the young ones. NEP convincingly claims to restore that cultural confidence by which we will never feel reluctant to study and teach not only Humanities and Social Sciences but also Natural Sciences, Engineering and Management Studies in our native languages with an unapologetic reliance on Indian Knowledge Systems that have to offer us for most of the disciplines invaluable resources in abundance. The idea is to ensure that our native languages and Indian Knowledge Systems which draw upon the insight and wisdom of the likes of Vivekanand and Aurobindo should be able to cater effectively to our educational needs and requirements in order to decolonise Indian mind, particularly young minds and in turn facilitate the growth of both individuals and the entire nation in an immensely positive and productive way.

Comments