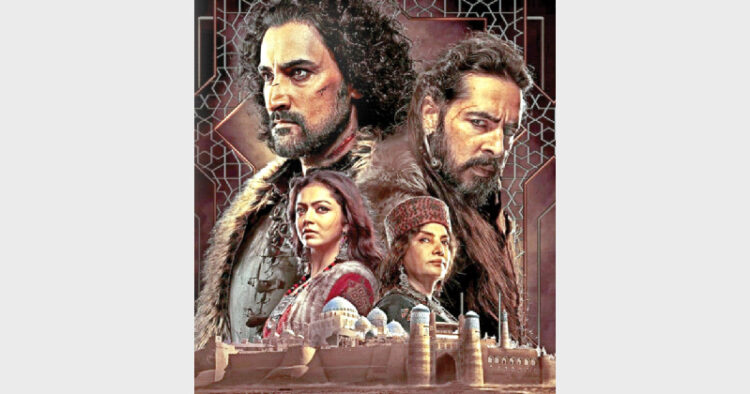

The latest Disney Hotstar offering “The Empire” has elicited a lot of response, with some comparing its visual effects to the superhit historical fantasy “Game of Thrones”, and others criticising it for its glorified portrayal of Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire in India. This eight-episode series seems to be a blockbuster entertainer at first, but as one moves from scene one to the last, the carefully concealed ideology of the film comes to light. Based on Alex Rutherford’s historical fiction “Empire of the Moghul: Raiders from the North”, the first episode shows Babur as an inquisitive, poetry-loving, harmless, humane teen who loses his father in an earthquake that strikes their kingdom Ferghana.

Portraying Babur as Hero

An emotional Babur is forced to take over the reins of his father’s kingdom at a time when he is neither prepared nor willing to do so. His grandmother, played by Shabana Azmi, is shown as a key player in his rise to power, right from his coronation to his sack of Samarqand, and even later. A family-loving, respectful Babur appears to be the hero of this make-believe cinematic blunder, which not only fails to arouse any response but also appears to be purposive and absurd.

Costumes Out of Place

A fantastical rendering of a period in which all men fought for glory and plundered everything that came their way, ‘The Empire’ is a disaster even as far as costumes are concerned. The use of ikat and ajrak fabric, Babur wearing a nose pin, Khanzada Begum wearing something like a tube top, the mistress of Umar Shaikh dressed in a slit skirt paired with a skimpy top, borders on insanity. Ajrak is native to Sindh and Gujarat and ikat is native to Indonesia, though popular in many parts of South and South East Asia. Ikat was certainly not in use in Afghanistan in the medieval period.

Bejewelled Babur

According to injunctions of the hadith, a Muslim man is not permitted to wear any jewellery either in his nose or ears, and Babur being a practicing Muslim could not have taken the liberty to go against the directives of his faith. In medieval times, women were not supposed to appear in public immodestly, and hence women being shown with off shoulder dresses in some scenes is completely misleading.

Babur’s main adversary, Shaibani Khan, played by Dino Morea, is projected as a ruthless tyrant and a genocidal maniac. From the first episode to the fifth in which he is killed by the allied forces of the Shah of Iran and Babur, Shaibani Khan is shown as an immoral lout. This is in complete contrast to the way in which Babur has been projected, as a just, compassionate, and considerate soul who indulges in warfare only because he is left with no other option. A dialogue between Khanzada Begum, his elder sister, and Babur in which the former says that the only difference between him and Shaibani Khan is that Babur has “insaniyat” puts a lid on all speculations of the series being neutral. This dialogue and many other scenes shamelessly glorify the Mughal marauder. What could possibly have been the difference between Shaibani Khan and Babur, both belonged to the same region, both were competitors, both were fanatics, and both were equally passionate about warfare and loot.

Historically, Babur’s sack of Samarqand was no less bloody than the territorial conquests of any of his adversaries. Countless people were massacred by his army, not only in Uzbekistan but also in India

Shaibani’s lustful advances towards Babur’s elder sister, Khanzada, and Babur’s romantic liaison with Maham Begum, his chief consort, are also debatable. Khanzada Begum is shown as a prisoner of Shaibani in Samarqand after his conditional agreement with Babur for providing him and his family a safe passage back to his kingdom, but by his own admission in his memoirs, “Baburnama”, his sister is supposed to have been left behind due to frenzy caused during the exodus. Babur has not mentioned any compromise deal with Shaibani Khan in which the latter asked for his sister’s custody as a perquisite for Babur’s departure to his kingdom.

At this exodus, my elder sister, Khān-zāda Begīm fell into Shaibāq Khān’s hands (Baburnama, translated by Annette Susannah Beveridge, p. 134).

Shaibani Khan’s cruelty cannot be overlooked but the question to be asked is whether he was the only cruel one in Uzbekistan? Was Babur not cruel at all? Could one ambitious monarch ever be less cruel than the other? How does one distinguish between the levels of cruelty? The makers of this drama series perhaps didn’t apply their mind to such intense historical questions or perhaps research is not their forte. Whatever their reason for not relying on research, the makers shouldn’t have made the mistake of considering the audiences to be naïve.

Excesses by Babur’s Army

Historically, Babur’s sack of Samarqand was no less bloody than the territorial conquests of any of his adversaries. Countless people were massacred by his army, not only in Uzbekistan but also in India. His raids in the North brought misery and doom to the people and his army is known to have committed excesses against women and children but in the series, it is only Shaibani Khan who is the personification of evil while Babur is a kind-hearted, benevolent monarch who rewards loyalty and respects friendship. Two powerful kings or generals fighting it out on the battlefield perhaps was the mainstay of medieval history across the world, but to portray one as a protagonist and the other as an antagonist with the intention of pushing forward a certain narrative is problematic.

Coming to Babur’s conquest of Hindustan, the scenes of the First Battle of Panipat are undoubtedly a visual delight and the historicity of Babur’s victory in the battle due to the use of cannons and muskets cannot be denied. However, the dialogue between him and his eldest son, Humayun, prior to his departure for Hindustan is a piece worth revisiting. In episode 6, Babur tells a restless Humayun- Logon ki jaan lene se kayi zyada bahaduri ka kaam hai logon ki jaan bachana (Saving the lives of people is a much more valiant act than taking the lives of men on the battlefield). Coming from an invader who massacred people left, right and centre, this dialogue seems to be too far-fetched. Babur has been glorified as the founder of the Mughal empire in many history textbooks but this series has taken it to a completely different level.

Hiding Invader’s Distaste for Bharat

The element of fiction has overridden history to such an extent in the series that Babur’s dream of conquering Hindustan is shown as a poetic imagination inspired by his father, Umar Shaikh Mirza II. The poetry of Amir Khusrau in Braj Bhasha narrated by his father to a young, impressionable Babur is supposed to have been his inspiration for sacking Hindustan. The dreamy obsession of a young Babur materialising into reality is the central theme of the story with ample references to his merciful and charitable demeanour. Anyone well-versed with the Baburnama would know of Babur’s distaste for Hindustan. He made his displeasure about the country amply clear in his memoirs:

Hindūstān is a country of few charms. Its people have no good looks; of social intercourse, paying and receiving visits there is none; of genius and capacity none; of manners none; in handicraft and work there is no form or symmetry, method or quality; there are no good horses, no good dogs, no grapes, musk-melons or firstrate fruits, no ice or cold water, no good bread or cooked food in the bāzārs, no Hot-baths, no Colleges, no candles, torches or candlesticks (Baburnama, translated by Annette Susannah Beveridge, p. 390).

Babur’s conquest of India cannot and should not be seen through the prism of a childhood dream coming true. It must be seen in the context of Central Asian geopolitics, Babur’s desire to conquer a new land, and his intention of waging Jihad (Holy War) against the infidel rajas of Hindustan.

The series, directed by Mitakshara Kumar and created by Nikhil Advani, fails to show the actual face of Babur, a raider and looter who was as ferocious and savage as his adversaries. This project which aims to exalt the virtues of Babur is but a failed one as most people with some sense of history know who Babur was and what he did in areas he conquered. The special effects might blur the vision of some viewers who might temporarily be tempted to believe what they are being made to see, but a deeper analysis of the series leads to a comprehensive critique of this larger-than-life on-screen depiction of this Turko-Mongol freebooter.

Comments