—Agrah Pandit

“The oriental dress is suited to a life of leisure, indolence, and slow motion, whereas the Western costume indicates an active and self-confident life.”—a The Hindu editorial of 19th century.

“It’s easy to wear a saree. Wars have been fought in saree. Grandmothers have slept in saree and woken up without any folds to it.”—Sabyasachi Mukherjee, 21st century.

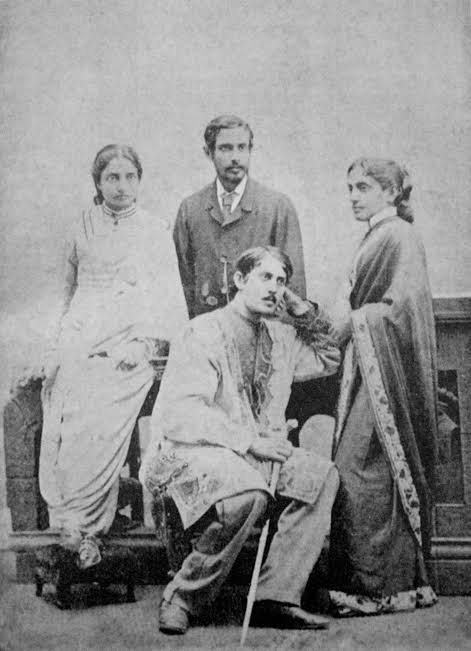

Once there was a curious advertisement in 19th century women’s magazine Bambodhini Patrika. The ad offered to train women in how to drape the saree in a novel, elegant and more convenient way. In this style, the aanchal or pallu was carried around the body, pinned on to the left shoulder and then thrown backwards. It, thus, freed the hands for running various errands and paying courtesies by freeing the working hand. The wearing of undershirts and petticoat underneath, in this new style, rendered the saree as a modest outdoor wear. The maverick woman behind the ad and this new style of draping, which soon became the most recognizable attire for Indian women, was Jnanadanandini Devi, the sister-in-law of Nobel laureate Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore.

Brahmika Sari

During 18th century, the British had used the inferior status of Indian women as an indicator to India’s backwardness, and thus, as a justification for the British rule. Women were hardly visible in public life then. One of the causes was that the traditional Bengali saree had not yet evolved as a suitable outdoor wear. It was worn without a blouse or a petticoat, by tucking it in waist and in broad box pleats. Though convenient in wearing, cheap, environmental-friendly, one-size-fits-all and most common-sensical attire in a tropical country, traditional modes of wearing saree rendered it unsuitable as an outdoor wear. Without modification, it could also result in wardrobe malfunction.

Gyanodanandini Devi had to face problem when she moved in an ‘oriental dress’ with her husband to Bombay from Calcutta. Her husband, Satyendranath Tagore, was the first Indian to make to Indian Civil Service in 1864 and Bombay was his place of posting. During this sojourn, she wore an unwieldy dress-cum-sari held together through many pins and tucks.Given that her husband belonged to an elite class of civil servants, she was required to socialize and accompany her husband to various parties and outdoor events. Something needed to be done about saree.

In Bombay, she observed the outdoor wear of Europeans as well as of Parsi women. In their lifestyle, strict zenana tradition (confining of women to interiors of house) was absent, and women’s street wear was suitably evolved.

She observed that Englishwomen wore blouse with sleeves, ribbons and brooches. She observed that the Parsi women wore blouse and petticoats under their silk gara saris. She further noted that Gujarati women and local fisherwomen took ulta pallu (pallu thrown over the left shoulder). She combined all these elements to produce what came to be known as Brahmika saree or Nivi (Nivi-new) style. Maharani Suniti Devi of Cooch Behar later added frontal pleats to it. In coming decades, this style became the predominant outdoor style of draping as more and more women involved themselves in the public life.

The Nivi saree gave a new kind of sartorial freedom to women. It was modest; more suitable to walking fast; easier to combine with shoes, sweaters and coats; easier to carry.

As one writer comments that much like Indian nationalism, Nivi style too emerged out of the dialogue between tradition and modernity where the addition of petticoat and blouse acted as a mark of an ‘emancipated modern woman’. As more women participated in national movement, the Nivi sari became the part of ‘modest Indian woman’ narrative.

Sari, having been given an outdoor facelift, also became an attire par excellence of Indian culture. Women visible in Nivi sarees in public life also retorted to British’s charge that the Indian woman, relegated to her indoor duties, with the sole role as wife and mother was a proof of India’s backwardness. An outdoor, working woman who was rubbing shoulders with men was an empowering sight.

Nonconformist Devi

Back in Calcutta, an ever-rebellious Jnanadanandini Devi shocked the high Bengal society by accompanying her husband to a Christmas ‘party’. She introduced the system of ‘evening outings’ and ‘birthday parties’ in Bengal society. She was behind the gradual opening of zenana in the traditional elite households of Bengal. When her free spirit began to cause discord within Tagore household, she left Jorasanko to live by herself in a mansion on Park Street nearby. It was the earliest instance of a nuclear family among upper-caste Bengali society. In another scandal, she appointed a Muslim woman as a wet nurse for her children. In yet another instance, a pregnant Jnanada set sail for England with her three children. Remember this was a time when crossing the seas for Indian women was rare, let alone without a male companion.And yet she set sail abroad with her children by herself—that too when she was in an advanced stage of pregnancy! She advocated marriage alliance of Tagore family with non-Brahmin Cooch-Behar royal family which once again brought her into conflict with elder male members of the family.

Coda

The versatility of saree has ensured that it has not met the fate of traditional dresses like kimono. Kimono, a traditional Japanese dress is worn today only on formal occasions. Saree, on the other hand, has been adapted for indoor, outdoor, party, dance, and even as gym wear. Further, as against kimono, saree is and was always available to all social classes. It has fairly long history. It is not uncommon to spot the sights of, from transgender women to bollywood celebrities, flaunting their sarees on social media as well as in public. Amidst all such celebrations of saree, we shouldn’t forget that lady Tagore who contributed to the evolution of saree in a big way.

Comments