This is the boldest of Amish’s writings so far where he has come out of his comfort zone. He has not spared us for our divisions that made us easy meat for the enemies. He is forthright when he speaks of the brutality of Islamic invaders in the name of religion, just as he is about Indian weaknesses.

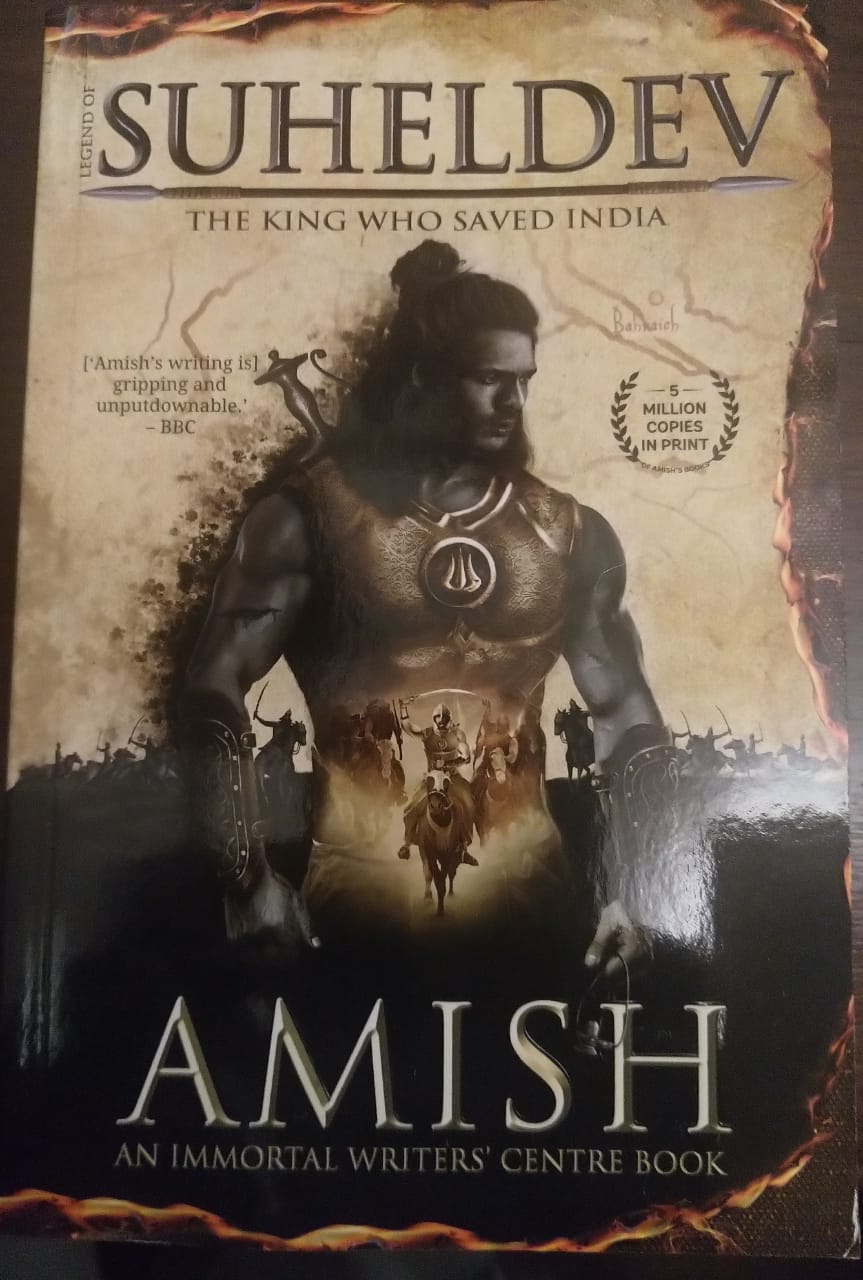

Most of Indian youth have grown up on Amish Tripathi’s Meluha and Ramchandra Series. They are fictionalised accounts of the most revered of Gods of Hindus – Bhagwan Shiv and Bhagwan Rama. They are presented in believable story lines with believable miracles attributed to them. These books are a result of divine reverence that the author Amish has for these fountainheads of Hindu civilisation or what many prefer to call Bharatiya or Indic civilisation, or Sanatan Dharma. His collection of essays – Immortal India gave the youth a direction about an aspiring India. However, this time, Amish has dived into unknown waters.

Here the waters have deep running treacherous currents. He is swimming against the flow of history dictated by Marxist historians. It is a flow of narratives that is based on denial or our past or ‘negationism’ as Konraad Elst puts it. The first pearl he has discovered in his dive into these swirling waters is King Suheldev. Ours is, now, a history sanitised and landscaped by careful curators of Left where you walk through the great Mughal gardens smelling of roses and intoxicating beautiful flowers irrigated with ‘Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb’. There is nary a whisper that these landscapes are built on the mortal remains of millions of innocent Indians, thousands of braves who never accepted slavery and fought the invaders all through their rein, not giving up. The stench of decaying history is sought to be covered up with sprinkling of feel-good fragrance of make believe world of great secular invading Turks, Mughals, British et al.

Unfortunately for our myth-makers our civilisational memory based on oral history, folk songs and local historians hasn’t allowed the ghost of the past beneath these make believe beautiful gardens to go away. Some memories pop up, some giants leap out of our collective memories despite sustained attempts to swat them away. For reasons unknown to common Indians, their sense of pride of their perennially flowing civilisation is sought to be crushed even after the British departed. British had an agenda. What is the agenda of our current historians ruling by proxy on the back of politicians with no intellectual depth? We can only hazard a guess.

There are many books in regional languages, many stories of our resistance, our valour that our people have not forgotten. But, our youth being educated more and more in English is deprived of this knowledge. This is where Amish has made his signal contribution by telling the stories from and about history. Though “Legend of Suheldev – The King who Saved India” is a fiction, it faithfully reflects real history.

The novel opens with the savage destruction of Somnath temple by the barbaric invaders, bent upon destroying the faith of ‘kafirs’ worshipping idols or ‘butparast’ in invaders’ language. One comes face to face the brutal senseless destruction of art, spirituality and faith. There is no escape from the extremely debased violent nature of the invaders.

Then, the author goes on, to turn the knife into Indian conscience by showing the prevalent caste biases, false pride about one’s caste and divisions within Indian society. It hurts, but Amish is relentless. The thrust of this entire novel is lack of unity in our society, basically due to caste structure and parochialism, and how the invaders took and still take advantage of this division. But, if there is a kshatriya king who is ready to be a slave to an Islamic invader rather than work with a low caste king, there is also an Indian Muslim whose love for his motherland doesn’t allow him to be lured by the call of violent pan-Islam. He refuses to buy the cruel and barbaric definition of Islam. There are more Muslim characters here who are show preference for the Sufi tradition against the violent strain of Islam.

In the war of civilisations, the contrast between the Islamic and Hindu way of life is brought out dispassionately by Amish, “The strength of Islam of the Turks is that it is socially inclusive but its weakness is that it is theologically intolerant. On the other hand, the Hinduism of us Indians is theologically inclusive and liberal, while socially we are intolerant.”

Suheldev represents the undying spirit of a nationalist who refuses to give up because of Indian, or I dare say, Hindu weakness. He goes onto create a confederation of kings and puts up a formidable fight against the enemy from Ghazni, Salar Maqsud. He adopts every mean to defeat the enemy.

Casting his vision wide, the author, brings in the destruction of Buddhist society and its monks. Afghanistan history shows how it is futile to practice non-violence against a violent enemy who follows no dharma, nor the rules in a war. The violent end of the Buddhist abbot brings out danger of simplistic view of non-violence. A character raises the dilemma thus, “I feel people often mistake love for peace for weakness. They look upon those who talk of love with contempt and keep pushing them. If I turn the other cheek and somebody hits me again, then what am I supposed to do?”

Legend of Suheldev is peppered with battles where violence is described graphically, but nowhere does the author glorify it. Questions are raised about futility of war time and again. At one place Suheldev says, “The biggest fear in fighting a monster is that in fighting the monster, we ourselves will become like the monster.” He guards against this risk all through his life.

In the war of civilisations, the contrast between the Islamic and Hindu way of life is brought out dispassionately by Amish, “The strength of Islam of the Turks is that it is socially inclusive but its weakness is that it is theologically intolerant. On the other hand, the Hinduism of us Indians is theologically inclusive and liberal, while socially we are intolerant.” These few pages are the best part of the book where the author brings out, very lucidly, why this war being fought by Suheldev was crucial. What he philosophises in these pages is relevant in the present too.

Responding to the Marxist apologia about loot and destruction by Islamic invaders, the author tells bluntly through the hero, “Why do you think they attack our temples and destroy our idols? Wouldn’t it be more logical and rational for them to treat the idols as hostages and force us to give them money? They don’t do that because they are using our belief and faith to destroy our morale, to destroy our spirit. Because, they think that conquering a demoralised populace is much more easier. We have to pay them back in their own coin.”

This is the boldest of Amish’s writings so far where he has come out of his comfort zone. He has not spared us for our divisions that made us easy meat for the enemies. He is forthright when he speaks of the brutality of Islamic invaders in the name of religion, just as he is about Indian weaknesses.

Most importantly, he tries to extricate our heroes from the stranglehold of caste. It is a tragedy that we are being influenced to reduce our national heroes into caste or regional heroes. A Chola or a Palava remains a Southern hero, Shivaji is reduced to a Maratha hero, Rana Pratap becomes a Rajput hero of Rajasthan, and Guru Gobind Singh is confined to Punjab as a Sikh warrior. We forget that they sacrificed their all to protect dharma. Freedom fighters too are slowly being reduced to their regional and caste identity. Dr Ambedkar, a national hero, greatest of scholar of his time, is downsized to a leader of Dalits. We have degraded ourselves so much that now we even look at our army through caste lens.It seems that the efforts of Suheldev’s admirers is not to see him as a national hero of resistance but as hero of one caste or the other. With this novel, Amish tries make us rise above smaller identities and think of nation.

Isn’t it ironical, that there is a majaar to celebrate Salar Maqsud in Bahraich, but talk of glorifying Suheldev, you are labelled a communalist preaching hate based on a myth. Our pride for our heroes is so shallow that there is a beautiful well maintained majaar for Afzal Khan where Shivaji killed him, below the historic Pratap Garh, but Pratap Garh is in shambles of careless upkeep.

Amish Tripathi has introduced the concept writers’ collective for the first time in India. I think, it is a move worth appreciating. It will help him present to us, more stories whirling in his mind. He has been generous in his praise of his team and open about it, rather than using ghost writers. His touch is visible all through the book. There are hundreds of our unsung heroes. They need sculptor of words like Amish to tell their stories. I am sure, he will inspire many writers the way he inspired many of them earlier to reinterpret our ancient scriptures and stories.

To paraphrase Claude Alvares, “All histories are elaborate efforts at myth-making. Therefore, when we submit to histories about us written by others, we submit to their myths about us as well. Myth-making, like naming, is a token of having power. Submitting to others’ myths about us is a sign that we are without power… If we must continue to live by myths, however, it is far better that we choose to live by those of our own making rather than by those invented by others for their own purposes….That much at least we owe ourselves as an independent society and nation.”

Let us retell more stories of our heroes and our undying perennial civilisation.

(The writer is the author of RSS360° and several other notable works. He is a Columnist and well-known TV Panelist)

Comments