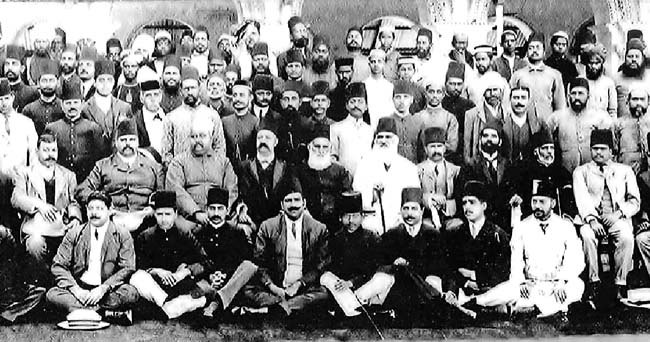

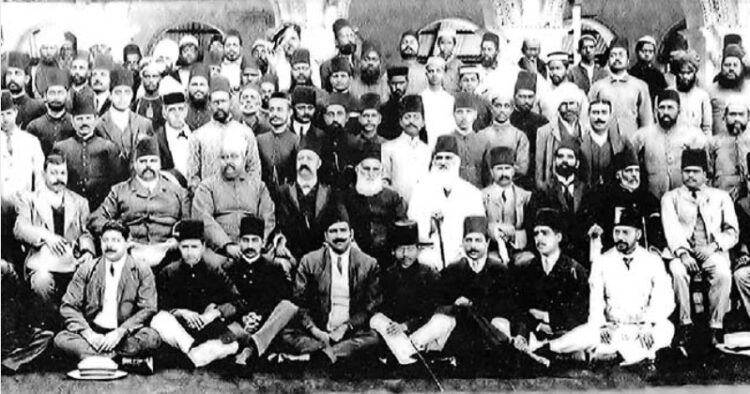

The founding members of the All India Muslim League at

the baradari of Shah Bagh in Dhaka on December 30, 1906

the baradari of Shah Bagh in Dhaka on December 30, 1906

The rise of Muslim political parties in British India in Bengal and their primacy of religious identity over national identity is inextricably intertwined with the history of India’s Partition

Sanjoy Som

The Partition of Bharat in 1947 was not the first one of the country. Her colonial rulers had carried out several such divisive acts over and over again during their occupation in pursuit of their common agenda of preventing Bharat from realising her past civilisational glory, her rich cultural heritage and her righteous ethos, all of which were far richer than any inherited legacy that her colonial masters could ever claim for themselves. The penultimate attempt was made to divide the people of the then Muslim majority Bengal in 1905 on religious lines that later got undone due to protests led by some of the most eminent citizens like Rabindranath Tagore, but this division also simultaneously led to the growth of Muslim political parties in India. The British policy of ‘Divide and Rule’ ultimately resulted in growth of politics of religion, politics of alienation and the consequent Partition of Bharat in 1947, followed by ethnic cleansing of Hindus from both East and West Pakistan. It has widely been explained in the book ‘Muslim Politics in Bengal: Legislative Perspective’ Vol 1, edited by Snehangshu Bhattacharya and published by Institute of Social and Cultural Studies.

Despite severe protests, mostly by the Hindu intelligentsia of Bengal, the first Partition plan of Bengal was put to effect by the British on October 16, 1905. The Muslim aristocrats and elite of the region sensed an opportunity to regain their lost political power from the educated Hindus of Bengal due to their sheer numeric strength in Eastern Bengal and Salimullah, the Nawab of Dacca, almost immediately formed a group of likeminded landed Muslim elites and founded the Eastern Bengal and Assam Provincial Muhammadan Association to defend the formation of the new province. This was truly the beginning of the politics of religion. On December 30, 1906 a decision was taken at Dacca Educational Conference to form a political party only for the Muslims in British India and thus came into existence the All India Muslim League. Though the League emerged from the division of Bengal, the reigns of the party went into the hands of Muslim leaders outside Bengal and two separate branches of this parent party got opened in the two divisions of Bengal: the Eastern Bengal and Assam Muslim League in the east and the West Bengal Muslim League in the west.

Due to tremendous public pressure and continuous opposition by the ‘Who’s Who’ of Calcutta, the division of Bengal finally got undone on December 12, 1911. This created a challenge for the League in the sense that it became imperative to seek amalgamation of its two branches into a single unit and manage vested interests too, all at the same time. On March 2, 1912 Nawab Salimullah was able to deftly handle a difficult amalgamation process and thus was formed the Bengal Provincial Muslim League as a branch of the All India Muslim League, with Fazlul Huq elected as President. Abdul Kasem Fazlul Huq was one of the most eminent lawyers of the Calcutta and Dacca High Courts who later got elected to the Bengal Legislative Council from Dacca from 1913-21, served the Central Legislative Assembly between 1934-36, was elected as a member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly from 1937-47 and went on to become the Prime Minister of Bengal during those tumultuous years 1937–1943. With Fazlul Huq at the helm in Bengal, All India Muslim League began its journey towards gaining real political power which finally led to the trifurcation of India in 1947. After the death of the moderate Nawab Salimullah, the second annual session of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League held in Burdwan on April 24, 1916 saw the League virtually come of age and with the death of Deshbandhu CR Das in 1925, the pretence of emphasising on Hindu-Muslim political unity in the Bengal League also almost became redundant.

Meanwhile, prominent Muslim leaders realised the opportunity that religion based politics had on offer for them and while some resigned from the Congress in 1926 including Abdul Matin Choudhury, Nurul Haque Choudhury, Abdul Majid Khan, Samsuddin Ahmed, etc., others like Maulana Akram Khan and Abdullah Al Mamun Suhrawardy resigned from the Swarajist Party. Then all hell broke loose and 1926 saw a catche of Muslim political parties emerge like the Bengal Muslim Council Party co-founded by Rashid Khan, Akram Khan, Fazlul Haq (by then leader of a splinter group of East Bengal Muslim League) and Mujibar Rehman (editor of The Mussalman and later the founding father of Bangladesh), The Bengal Muslim Party of Sir Abdur Rahim and the Independent Moslem Party led by Hussain Mohammad Suhrawardy and later joined by Mujibar Rehman who could not coexist with Fazlul Haq for long, all parties competing with each other for a chunk of the same Bengal Council Area pie. In the Bengal Provincial elections of 1926, Sir Abdur’s Bengal Muslim Party emerged as the single largest group but the other two Muslim organisations also got seats, and thus emerged the first ever Muslim block inside the Bengal Legislature. This block however remained divided and in the 1929 elections none of the parties, including the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, could obtain an absolute majority in the 39 seats allocated exclusively for the Muslims. Soon they realised that their strength lay in unity and thus was formed the Nikhil Banga Krishak Praja Samity initiated by Nawab Habibullah, son of late Nawab Salimullah of Dacca in 1929 with Sir Abdur Rahim as Chairman of this political umbrella outfit. Thereafter, for the first time most Muslim leaders unitedly began to reach out to the Muslim peasantry and the middle class of Bengal by way of organising Praja Sammelans at district level and garnering widespread political support for their religio-social brand of politics.

Sir Abdur Rahim is a perfect test case of the mindset of the mainstream Muslim leadership that was emerging in Bengal. He was born in a rich educated Zamindar family in Midnapore, was educated at the prestigious Presidency College and then called to the Bar at British Inns of Court, began practising as a Barrister in Calcutta High Court and went on to become the Chief Justice of Madras High Court and the Tagore Professor of Law in the University of Calcutta. Entering politics, he became a member of the Bengal Provincial Executive Council and served as the province’s Administrator of Justice and Allied Subjects from 1921 to 1925. He became an influential founding member of All India Muslim League and chaired their Aligarh Conference in 1926. In his speech, this highly educated, affluent, highly decorated and well placed gentleman said, “The Hindus and Muslims are not two religious sects like the Protestants and Catholics of England, but form two distinct communities of peoples, and so they regard themselves… the fact that they have lived in the same country for nearly 1,000 years has contributed hardly anything to their fusion into a nation… Any of us Indian Muslims travelling in Afghanistan, Persia, Central Asia, among Chinese Muslims, Arabs and Turks would at once be made at home and would not find anything to which we are not accustomed. On the contrary in India we find ourselves in all social matters aliens when we cross the street and enter that part of the town where our fellow townsmen live.” [S.M. Ikram, Indian Muslims and Partition of India (Atlantic Publishers & Distributors,1992) pp.308-310]. Sir Abdur Rahim got elected to the Central Legislature in 1929 and the Chair at Nikhil Banga Krishak Praja Party fell vacant and by 1936 the leadership of the party fell in the hands of the more radical elements from East Bengal led by Fazlul Haq and was renamed Krishak Praja Party.

In effect, the Muslim peasantry got united under the banner of Krishak Praja Party, the Muslim aristocrats regrouped under the banner of a newly formed political outfit led by Nawab Habibullah called the United Muslim Party and the Muslim business community based out of Calcutta led by Khawja Nooruddin and M.A.H. Ispahani formed the third political force and named it the New Muslim Majlis, all of this happened in 1936. And then arrived Mohammad Ali Jinnah in Calcutta in 1936 at the invitation of the Majlis and in a rally held on August 20, 1936 organised by Bengal Provincial Muslim League, Jinnah asked all Muslims of Bengal to rise above petty politics and “to rally around the banner of All India Muslim League”. However, Jinnah’s efforts to bring all Muslim Parties under the umbrella of All India Muslim League Parliamentary Board seemed to be failing due to conflicting interests of the landed and the non-landed class and also along Bengali and non-Bengali leadership lines, though the aristocratic United Muslim Party merged with the Board due to Jinnah’s pro-Zamindari tilt. Fazlul Haq felt that this move by Jinnah would make his Krishak Praja Party a minority in the Board. Despite his politics hinging on the issue of permanent settlement, he still decided to join the Board, only to exit from it in September 1936 and was subsequently expelled from the Muslim League Central Parliamentary Board on November 2, 1936.

The first general elections in lieu of provincial autonomy were held in 1937 and Krishak Praja Party having won 35 seats became the third largest party and formed a coalition government with the Bengal Provincial Muslim League and independent legislators. Fazlul Haq was elected as the leader of the House and the first Prime Minister of Bengal. Despite serious differences of opinion, Jinnah was forced to invite Huq to formally present Lahore Resolution in 1940, which envisaged ‘independent states’ in the eastern and northwestern parts of India for the first time, thereby sowing the seeds of Pakistan. Interestingly, the resolution said, ‘That geographically contiguous units are demarcated regions which should be constituted, with such territorial readjustments as may be necessary that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority as in the North Western and Eastern Zones of (British) India should be grouped to constitute ‘independent states’ in which the constituent units should be autonomous and sovereign.’ Jinnah was more vocal in an article that he wrote in a London weekly ‘Time and Tide’ on March 9, 1940, where his concluding remarks were, ‘While Muslim League irrevocably opposed to any Federal objective which must necessarily result in a majority community rule under the guise of Democracy and Parliamentary system of Government…To conclude, a constitution must be evolved that recognizes that there are in India two nations who both must share the governance of their common motherland.’ However this bonhomie between Jinnah and Fazlul Haq was short lived and when Haq decided to join the Viceroy’s National Defence Council in 1941 during World War II, Jinnah was not consulted and that led to the withdrawal of Muslim League from the ministry. Haq resigned on December 2, 1941 as Prime Minister of Bengal and Governor’s Rule was imposed.

The second Haq ministry formed on December 12, 1940 was perhaps the most interesting marriage of contradictions, with the Hindu Mahasabha led by Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee joining as a key member of the Cabinet to keep the League out of power, so much so that the ministry was popularly referred to as Syama-Haq ministry. Fazlul Haq’s second term as Prime Minister was fraught with the League’s propaganda that he was working against the interest of the Muslims because of his alliance with the Hindu Mahasabha on one hand and the tense relationship with the Governor on the other. The challenges thrown up by the British response against the fear of an advancing Axis force towards India’s north-eastern border, a devastating cyclone sweeping the coastal regions of Bengal with the British administration blocking relief work, a number of prisoners getting shot dead in the Dhaka jail with no enquiry being conducted and finally the call for Quit India Movement by the Congress in August 1942 plagued the Syama-Haq ministry. Dr Mookerjee finally resigned from it on November 20, 1942 in protest against repressive policies of the British administration and the Governor’s high-handedness. The early signs of the Great Bengal Famine due to the policy of denial of food by the British were already visible in 1942 and Dr Mookerjee threw all his weight behind relief work.

Fazlul Haq came under increased pressure from the Governor whose preference for a Muslim League led ministry was evident from two sponsored back-to-back no confidence motions moved in March 1943 that Haq managed to win by narrow margins. He finally resigned as Prime Minister on March 28, 1943 and Bengal Provincial Muslim League promptly formed a new government with Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin as Prime Minister from 1943-1945 followed by Hussain Suhrawardy from 1946-47. This diehard radical League man presided over the Great Calcutta Killing where 4000 innocent lives were lost and 10000 rendered homeless, mostly of Hindus. This was in response to Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s call for Direct Action Day on August 16, 1946 which was effectively a show of strength by the Muslims in Muslim majority provinces of India that forced Partition upon Bengal and India a year later.

In effect, what began as regaining of Muslim political power-play in Bengal in 1905 culminated in a separate nation for them in 1947. In that sense the history of the rise of Muslim political parties in British India in Bengal and their primacy of religious identity over national identity is inextricably intertwined with the history of India’s Partition. It is also the cause of extinction of millions of displaced people and subsequently of Pakistan’s inhuman persecution of her religious minorities, driving most of them away from what was once their homeland.

(The writer is a Kolkata-based analyst)

Comments