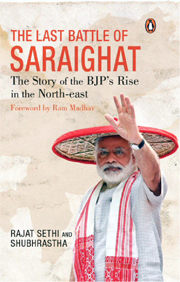

The Last Battle of Saraighat—The Story of the BJP’s Rise in the North East (Hardcover); The Last Battle of Saraighat—The Story of the BJP’s Rise in the North East (Hardcover);Rajat Sethi and Shubhrastha; Penguin Random House; Pp 182; Rs 599 |

Shaan Kashyap

Battle of Saraighat (1671) is the history of the spectacular triumph of Ahom army led by Lachit Borphukan over the might of the Mughals. The ascendancy of Mughals was challenged and overturned by Ahom people repetitively. The renown ingrained in this historical fact, no doubt, has persisted as trope of heroism in modern Assam. Thus, significant political battles in modern days must intensify by enacting themselves in the space of the cultural past. Rajat Sethi and Shubhrastha have shown the dexterity of situating an Assembly Election in the continuity of Assam’s past.

The book recounts the historical landslide victory of the BJP in Assam Assembly elections, but anatomy of the subject treatment is heedful to the North-East as a whole. The book is divided in six chapters with rich anecdotal evidence and hard facts. The foreword by Ram Madhav avails the oblivious readers to the much needed standpoint about the affairs in North-East!

The book commences by building upon the metaphor of the Saraighat. The readers are then introduced to the ‘history of political blunders’ as committed and commissioned under a long Congress rule. Taking cues from the political impropriety of the Congress, the authors have delineated the rise of BJP.

Five Decades of the Sangh

The significance of the book lies in the fact that it succinctly maps the growth of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in Assam. It thus, becomes a brief history of the long struggle and vital efforts of RSS in the state.

We are told that, “The RSS started its first seva in Assam in 1946 to help the ailing men and women suffering the brutalities of the riots of violence.” (p. 62) The Sangh held its first shakha in Guwahati on 28 October 1946. Thereafter, Sangh’s involvement in the socio-cultural storyline of Assam persisted and grew with issues. Guruji Golwalkar visited Assam in 1950, we are told, when the state was facing the affliction of an earthquake. Guruji established an organisation called ‘Bhukamp Peedit Sahayata Samiti’ which was received with much admiration. (p.63)

Sangh provided with the ideological force committed to its revered objective of a unified Bharat Mata. This was an alternative to the staunch and militant approach of ULFA. The RSS, we are told, esteemed the glory of the ancient past in Assam by tracing its history way back in time of Pragjyotishpur and Kamrupa. (p.65) The accomplishment of Sangh in “creating a counter- narrative in an atmosphere of vitiated political and intellectual environment has been one of the greatest achievements.” (p. 67)

We are told that by 1975, all districts in Assam had Sangh shakhas. This extensive growth also resulted in creating narratives which became the issue of prominence in 2016 Assembly elections. In the wake of Assam movement, the RSS played the crucial role in transforming the anti-bahiragat agitation to anti-videshi movements. Bahiragat referred to those who came to Assam from outside. The category was turned to the challenges posed by foreigners and the crucial difference between Hindus and Muslims was accentuated. Authors state that after a series of meetings, in 1980, Sangh stated that ‘Hindus were sharanarthis (asylum seekers) and Muslims were anupraveshkaaris (infiltrators) in Assam.’ (p.71)

How Sangh attempted to unify and integrate Axomiya conscience with that of Bharat is fascinating. The burning identity questions in post-colonial Assam were redressed by going back to the “religious, historical, quasi-historical and mythological accounts of Hinduism and India” to foreground the shared cultural liaisons. For example, the teachings of Srimanta Sankardeva were used by Sangh to integrate Assam with Bharat, both culturally and socially.

Writing on the Wall

Since both the authors have been an integral part of the local electoral campaign in Assam, their analysis is more substantial than merely intuitive. They have successfully mapped the rise of the BJP historically and the long struggle has not been blown away in the contemporaneity of the events.

Overall, the book is a welcome addition to the growing corpus of political commentaries on the rise of the BJP. The biggest takeaway in this case, however, is that the alertness of past has not been left compromised. As Ram Madhav rightly puts it that authors’ experience “would be of immense value to… not just the BJP in the North-East but also the North-east itself.” n

Comments