CA Dr VM Govilkar

India, once called a third world country, under developed country, developing country has of late been recognised as an emerging economy. How can India be among the world’s fastest growing economies and yet have hunger and malnutrition levels worse than that of Sub-Saharan Africa? India accounts for a third of the world’s poor, says World Bank. Almost half of the country’s children under five are classed as chronically malnourished, and more than a third of Indians aged 15 to 49 are undernourished, according to India’s National Family Health Survey in 2006. Fifty-four per cent of our women suffer from anaemia. It is a question that not only a welfare state should answer but a question about the fundamental right of life of human beings. Looking from this angle, the much discussed and debated Food Security Bill is a very progressive step. It has very good intentions and the courageous policy.

The Bill in Short:

1. Who are entitled?

— The bill dwells on targeting the BPL-APL issue (‘priority’ and ‘non-priority’ households). Intended benefits will be provided to people based on these categories. Priority households are entitled to 5 kgs of food grains per person per month, and Antyodaya households to 35 kgs per household per month.

— Children’s Entitlements

• For children in the age group of 6 months to 6 years, an age-appropriate meal, free of charge, is proposed to be provided through the local Anganwadi.

• For children aged 6-14 years, one free mid-day meal every day (except on school holidays) in all Government and Government-aided schools, up to Class VIII.

• For children who suffer from malnutrition, meals will be provided free of charge “through the local Anganwadi”.

• Entitlements of Pregnant and Lactating Women

Every pregnant and lactating mother is entitled to a free meal at the local Anganwadi (during pregnancy and six months after child birth) as well as maternity benefits of Rs 6,000 in instalments.

— The bill, if passed, would provide subsidised food grains to 75 per cent of India’s estimated 833 million rural population and 50 per cent of an estimated 377 million urban population.

2. At what price?

The PDS issue prices as given in Schedule I of the Bill are as under Rs. 3/- per kg for rice, Rs 2/- per kg for wheat, Re 1/- per kg for millets. These may be revised after three years.

3. Who are eligible households?

— The Bill does not specify criteria for the identification of households eligible for PDS entitlements.

— The Central Government is to determine the state-wise coverage of the PDS (proportion of the rural/urban population).

— The identification of eligible households is left to State Governments, subject to the Scheme’s guidelines for Antyodaya, and subject to guidelines to be “specified” by the State Government for Priority households.

— The identification of eligible households is to be completed within 365 days.

— The lists of eligible households are to be placed in the public domain and “displayed prominently”.

4. What are the Obligations of Government and Local Authorities?

— Central Government to provide food grains (or, failing that, funds) to State Governments, at prices specified in Schedule I.

— State Governments to implement the relevant schemes, in accordance with the Central Government guidelines.

— Local Authorities and Panchayati Raj Institutions are responsible for proper implementation of the Bill in their respective areas.

A law guaranteeing very cheap food to millions of people is certainly well-intentioned.

The grey areas

Mere good intentions do not help bring in desired results. Intentions must be supported by flawless policy, well defined procedures and sufficient financial support. How can one evaluate the Food Security Bill on these parameters?

1. Cost for Implementation–

At the proposed coverage of entitlement, total estimated annual food grains requirement is 612.3 lakh tons and corresponding estimated food subsidy at 2013-14 costs is about Rs 1,24,724 crore (estimates by Government). Increase in the wages and prices of seeds & fertilisers will increase the prices of food grains. The number of beneficiaries will also keep on increasing year by year. Hence the total subsidy amount will rise. Mr Ashok Gulati, Chairman, Commission for Agricultural Cost and Prices has estimated the amount at Rs 2 lakh crore. The budget provision for food subsidy is only Rs 95,000 crore. The question remains therefore that, from where the funding will be made to implement the scheme?

2. Identification of the beneficiaries–

The bill says that states will provide the list of the poor but they have no such records. The new bill doesn’t spell out the groups that qualify as beneficiaries nor the plans to identify them. The Government has constituted various committees to look at measures of poverty but they come up with different numbers. Unless the beneficiaries are indentified, how the implementation will be done?

3. Public Distribution Channel–

The scheme is proposed to be executed through the existing PDS. Under India’s existing food programme, as much as half of the grains procured by the Government are siphoned off by middlemen before reaching their intended beneficiaries, says a report by India’s Planning Commission in 2005. In a debate over the bill in India’s lower house on August 26, Food Minister KV Thomas also accepted that between 20 to 30 per cent of food is lost to leakages from the current public distribution system of food to India’s poorest. Much of the subsidised food, experts say, ends up being sold illegally in markets rather than in fair price shops. In other words when we want to distribute about 612 tonnes of grains, we will have to procure 1224 tonnes. Otherwise only half of 612 tonnes will reach the beneficiaries.

4. Worsening the fiscal deficit–

Government expenditure on social spending widened India’s budget deficit to 5.2 per cent of GDP last financial year. More provision for FSB will further take it to dangerous levels. It is estimated that the fiscal deficit this year may touch the level of 6 per cent which by all means is an unacceptable figure.

5. Loss of food grains-

According to the latest estimates, food grains worth Rs 236.32 crore were lost in the first quarter of 2013-14 which constituted almost half of food grains worth Rs 489.13 crore lost in 2012-13.

The reasons behind such losses is theft, loss of moisture, pest infestation, exposure to rains, negligence on part of concerned persons in taking precautionary measures, etc. If the volume of food grains available for distribution under FSB increases to more than 60 million tones, can we afford the losses?

6. Back-end infrastructure–

If we look at the bill closely, 60 million tones would be distributed annually, i.e.5 million a month. This means 55 million tonnes would be lying in the warehouses and if buffer stock is added to it, we would need approx.100 million tonnes of capacity. The total storage capacity available for central pool stocks was 74.6 million tonnes as on July 30 this year. The gap needs to be bridged. The initiative should be taken by the Government itself because it is a Government-oriented scheme and building of warehouses by the private sector would be limited to commercial interests only.

7. Interest of farmers–

The bill will make the Government the biggest buyer, hoarder and seller of food grains. There is a clear feeling that this would distort the market mechanism and reduce the bargaining power of farmers. The bill makes no provisions for production of food or for support of small and marginal farmers who are food producers. The very low prices of the subsidised food will distort the market. The farmers who can’t sell to the Government-assured programme will lose out on the open market as prices will be forced down.

8. Producing enough food–

It will be a big challenge to ensure availability of sufficient food grains. What are we going to do in a drought or a flood? The production of rice and wheat might come down dramatically. If we tap the global market then the global price would shoot up along with the subsidy bill. There is also a possibility that the MNCs will insist for the GM seeds to meet the targets of food grains production. On the basis of the experience of hybrid crops will we show the courage of saying no to the GM seeds and still make the grains available to meet the commitment under FSB?

9. The bill does not specify any timeframe for the rolling out of the entitlements.

10. The Government should focus on productivity enhancement rather than on subsidising food at the expense of taxpayers.

11. Food security is necessary but not sufficient for nutrition security.

12. Willingness to work—

If a person is entitled to get 5 kgs of food grains at an average cost of Rs. 10/-, he may not have incentive to work and earn more. This will have an adverse impact on efficiency and productivity of 67 per cent of India’s population. Can any nation afford this? The experience of MGNREGA in case of assured employment is not different.

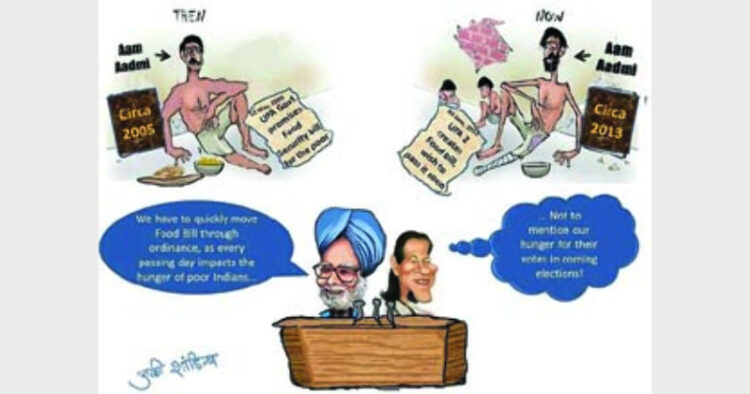

Let us therefore appreciate the intentions of FSB but at the same time take efforts to remove the grey areas so that the intentions are fulfilled and the FSB does not remain a political tool of vote grabbing.

(The writer can be contacted at [email protected])

Comments