Japan in need of love lessons

By Dr Vaidehi Nathan

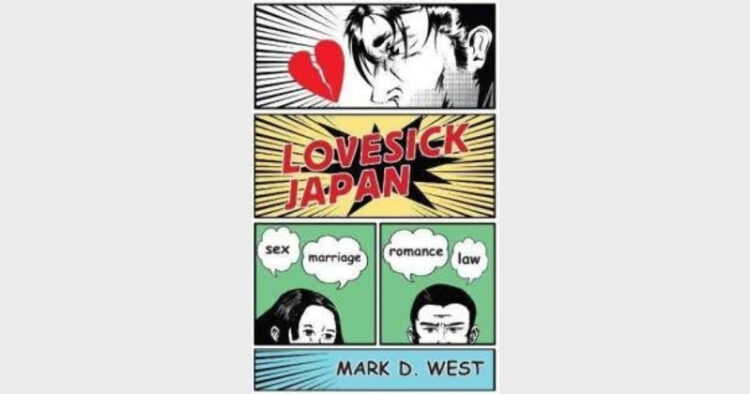

Lovesick Japan: Sex, Marriage, Romance, Law, Mark D West, Cornell University Press, Pp 259 (HB), $29.95

Japan is a nation of contradictions. While the people of the country enjoy a reputation for integrity world over, with almost myth-like stories of honesty coming out during the recent twin disasters of earthquake and tsunami and the resultant nuclear disaster, the prime ministers and the cabinets have been changing faster than the seasons, nearly all of them following financial scandals. While the Japanese are acknowledged as tradition-loving and even tempered, the perverseness of crimes are sometimes shocking. While traditionally women in that nation have had very little space in public life outside their homes, the country is today facing a falling birthrate because women do not want to have children. There is definitely a social disconnect.

Viewed against this background, Lovesick Japan: Sex, Marriage, Romance, Law by Mark D. West does not come as a surprise. Some of the most viewed children-adolescent category animated TV/internet serials originate from Japan. With very appealing line drawings and colourful images, most of these deal with stories of kids in the age group of 16 to 20. Love is the most predominant theme, more importantly unrequited love. Mark West in the book repeatedly points out this attitude towards love in Japan. “…the most striking feature of Japanese love narratives is their strong emphasis on suffering and pain. In Japan, love is often portrayed as a problem – an irresistible, destructive and life-threatening condition.” Even the dictionary meaning mentions “extreme sadness” in the context of love. What is adding to the intriguing scene is that the judiciary in Japan is very often called upon to judge the presence and absence of love in a crime and thereby decide the quantum of punishment. For, if love is a factor, the enormity of the crime is lessened. For instance, a stalker would receive less punishment if it is proved that he was in love and his crime was a result of that. Even serious crimes like adultery, rape and murder are passed through a prism of ‘love.’

Quoting several court cases and published judgments, Mark West makes interesting and sometimes astounding observations on the views, attitudes and beliefs in Japan on love, marriage and sex. It may be noted that there is, in their perception, no connection between the three. Marriages can both be loveless and sexless. The woman only has to comply with the ‘sense of the society’ to give children to the family. All kinds of sex-supportive arrangements thrive in Japan like the telephone club, date club, compensated date and health delivery. Each of these is veneered body-sale activities. According to a survey quoted in the book, 34.6 per cent of high-school girls were involved in one of these at least once. Similarly male masseuses and hairstylists are much sought after by the middle-aged Japanese women, for much the same reason, West says, quoting a ‘Love commentator.’

The focus of the book, in each aspect is the judiciary. “Japanese courts routinely present rape as a result of the absence of consensual sex. Conversely, if a man can have consensual sex, he does not need to rape.” In yet another place the author says “To judges, at least, love is characterised not by caring, romance, or sentimental warmth but by pain. If people fall in love, they suffer, in the most extreme cases to the point of death, experiencing overwhelming, unavoidable, and disruptive emotions… To Japanese judges, love is central to marriage in the abstract, but it is so unachievable in real-life marriages that its absence is expected. Marriage, then becomes a partnership, or a contract governed by courts.”

The book gives an insight into the turbulent social life of contemporary Japan, which is already reeling under falling birth rates, increased life expectancy, with the number of centenarians going up each year, family structure that is shrinking and traditional values that are fast burning up in the fire of westernisation. Mark West does not touch on the role and influence of religion in all this, probably in another book he would. Nor does he dwell on the history and civilisation aspects. Present day Japan is the focus and he does not stray from that. A keenly researched book, it is a good contribution to sociological studies. Mark D West is Nippon Life Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of Michigan Law School.

(Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca New York, 14850)

Comments