Bismarck: A sterling biography of a stunning life

By Dr R Balashankar

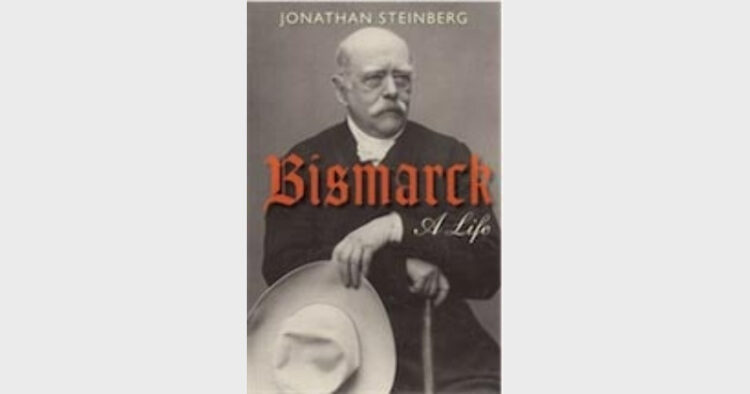

Bismarck: A Life, Jonathan Steinberg, Oxford University Press, Pp 577(HB), £25

“The great questions of the day will not be settled by speeches and majority decisions, but by blood and iron”, said Otto von Bismarck in 1862. His was a life lived by this conviction, who remade Europe, united Germany by the sheer power of his great personality.

Bismarck has many fans in India, especially those who concern themselves with the idea of nation building find in this fascinating life much to emulate and admire. The unification of Indian princely states by Sardar Vallabhai Patel to remake the Indian Republic after Independence involved greater patience, perseverance and sagacity, but much less blood and iron as compared to the arduous task of unifying Germany. This was perhaps because culturally, historically and geographically India was always one unlike Germany, which was more a political mission, achieved by tremendous grit and force. One can only wish that such well-researched, critical biographies are written on India’s heroes like Sardar Patel and Shivaji.

Bismarck: A Life, by Jonathan Steinberg is a remarkable biography of the political genius, whom the author rightly describes as the most influential political figure of the nineteenth century. From 1862 to 1890 Bismarck was the uncrowned master of Europe’s destiny, the man who said, “a statesman does not create the stream of time, he floats on it and tries to steer.” The exceptionally gripping biography of the extraordinary political visionary captures a three dimensional sense of the man, his moods, his fears, his personal style, the effect of all this on the people who came into his gravitational field. This is a critical portrait, the weakness, meanness, insecurity, suspicions and trivialities of the leader explicitly narrated from authentic first hand sources make the book immensely enduring. There is no attempt to idolise, rather the gross personal flaws that were a striking feature of the character of this statesman, make the reading more rewarding.

Many contemporaries believed that Bismarck’s power and his ability to hold on to it had something inhuman to it, says Steinberg, and adds, “Not even the devout Roman Catholic Windthorst could have believed that Bismarck was literally le diable, which he once called him but, as the greatest German parliamentarian of the nineteenth century and, perhaps, the shrewdest, Windthorst sensed, as others did, that there was an unearthly dimension to him, perhaps what Ernst Rentch and later Freud would call das Unheimliche(uncanny)… Yet Bismarck’s personality had such contradictions in it that it could be experienced as positive or negative –angelic or demonic – sometimes both at the same time.”

There are many ironies to the life of Bismarck. The book portrays Bismarck as a great statesman, who fought three wars, victoriously, and effectively ruled Europe for 28 years – all without commanding a single soldier, without commanding a vast parliamentary majority, without the support of a mass movement, without any previous experience of government, without the charisma of a great orator, and most interestingly, in the face of national revulsion at his name and his reputation. What was the secret of this mystique? He according to the author, was a genius of a very unusual kind. The book quotes extensively from the diaries and letters of his contemporaries to explore a “man who never said a dull thing or wrote a slack sentence.” He had a great sense of history. Some thought Bismarck ultimately was victim of a destructive self. He was an egoist. The book examines in great detail how the rural aristocrat, a farmer, with no military credentials, with a record of failure and irresponsibility in normal jobs and with a dissolute life-style became the great Bismarck of History.

His most powerful impulse was to dominate fellow human beings. This he displayed even as a school boy, his American friend in the university, John Motley, saw it in the 17 year old and wrote a novel about him long before he became the historic figure. He could charm anybody. He ‘bewitched’,; enchanted’, ‘charmed’, ‘delighted’ and ‘fascinated’, those who got bowled over by him he later reported. The price he paid for all that he achieved was terrible, suffering from hypochondria, hysteria, illness, sleeplessness, rage and over-eating. He destroyed much of his social life, the happiness of his children, the friendships of his youth and his own peace of mind. But his domination over his country was so complete that he was even called a dictator.

Bismarck ruled Germany by making himself indispensable to a decent, kindly old man who happened to be the King. He drew the King from his family and “inserted himself between man and wife and between father and son.” William I, the King and Bismarck, the chief minister shared a curious entente between them, his hold over the King upset the royal household, the two had “terrible rows, burst into tears, and collapsed afterwards.” In the end however, Bismarck got his way. The King would not always give in to his demands. If the King wrote or spoke sharply to him Bismarck would collapse into bed and was sometimes ill for weeks on end. The author quotes one of Bismarck’s contemporaries, writing about him thus, “that cynical cunning startled even the skeptical Schlozer in October 1862. He began to see Bismarck as a kind of malign genius who behind the various postures concealed an ice-cold contempt for his fellow human beings and a methodical determination to control and rule them. His easy charm combined blunt truths, partial revelations, and outright deceptions. His extraordinary double ability to see how groups would react and the willingness to use violence to make them obey, the capacity to read group behaviour and the force to make them move to his will, gave him the chance to exercise what I have called his ‘sovereign self.” In him we can see the greatness and misery of human individuality stretched.

Bismarck lived entirely for his country. His life is a great study for those for whom the country comes first and last. For that he manipulated and manoeuvred the sinews of power. His proximity to the King was for a purpose. He united his country at his personal peril. The prince did not like him. Once he became the king Bismarck fell victim to the palace coup and was summarily dismissed. With William-I he had a rapport. For 26 years the King and Bismarck lived in the constant love/hate relationship. He was clear in his mind the role he played. Perhaps that is why he insisted that the only epitaph on his simple grave should tell the truth about his career. ’A faithful German servant of Kaiser Wilhelm I.’

This is an excellent, undoubtedly one of the best biographies on Bismarck. Steinberg is an authority on modern European history and is professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

(Oxford University Press, Academic Division, Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2, 6DP, United Kingdom)

?

Comments