The best way to face the dragon is to tame it. That is exactly what India is doing

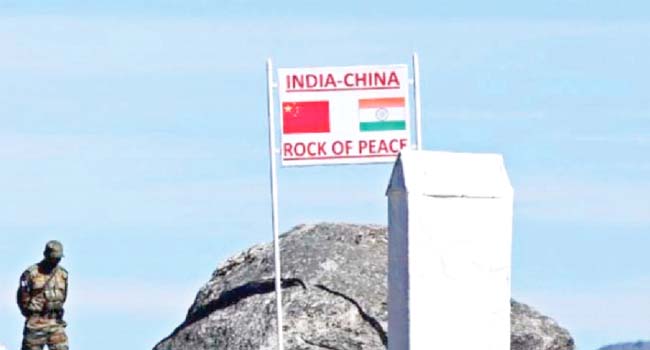

China and India move troops as border tensions escalate

In the ongoing battle for supremacy amidst the Corona crisis between the USA and China, the latter let lose its wolf-warriors signifying China’s new, more aggressive diplomatic response to countries critical of China. All of a sudden, China today is faced with a hostile global narrative blaming it for the corona pandemic, demanding an international enquiry and some countries even seeking reparation from China. China denied it vehemently but global onslaught led by the USA grew stronger by the day and Chinese media went to the extent of terming it ‘malicious slander against its national honour.’ “Wolf-warrior diplomacy,” named after two Chinese movies, describes offensives by Chinese diplomats to defend China’s national interests, often in confrontational ways. It is an example of soaring nationalism among the Chinese. “We will strongly hit back against malicious slanders and firmly defend national honour and dignity. We will layout the truth to counter the gratuitous smears and to firmly uphold justice and conscience,” said Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi while backing the “wolf warriors.” The global anger against China is so much that anti-China sentiments gained momentum; the majority of nations refused to relent. The Chinese “wolf warrior-diplomacy” failed to make much impact. On the contrary, saner voices at home began to call for restraint, saying that the new form of diplomacy is doing more harm to its national interests than gains if any. But China today is ruled by all-powerful Xi Jinping, while there is some dissension within the party, his diktat prevails finally.

“Wolf-warrior diplomacy” is evidenced not only in combative words but aggressive actions. China displayed its aggressiveness in the South China Sea by sinking a Vietnamese fishing trawler near the Paracel Islands in early April. In mid-April, the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources and Ministry of Civil Affairs jointly announced the naming of 80 islands, reefs, seamounts, shoals, and ridges in the South China Sea, triggering angry protests from other claimants. The last time China named islands and other geographical features in the South China Sea was in 1983, coinciding with the rise of China as an economic power. It also established new administrative districts on both disputed Spratly and Paracel islands. China was using the global fight against Corona to pursue its territorial ambitions as part of its traditional expansionist policy. The US intervention checkmated the Chinese actions in the South China Sea. India, however, continued to pursue its strategy of balance. But was the Chinese belligerence in South China Sea a warning to India which we failed to read? India’s change in FDI rules to stem Chinese predatory trade practices didn’t go well with China. Neither was China happy with India joining the comity of nations backing a draft resolution at WHO nor was it happy with the likely shift of global companies from China to India, much talked about re-location from China. The international community has realised that it is difficult to combat the dragon individually, but jointly the dragon can be tamed. The final icing on the cake which China couldn’t digest was the Chairmanship of the executive board of the World Health Assembly by way of which India could take to task both China and WHO. Domestic hardliners want India to support its ‘strategic allies’ on Taiwan and a global coronavirus review. China, for once felt threatened by India though India has made it clear that she wants to avoid power politics.

It soon made India also the target of its “wolf warrior-diplomacy”, first in the usual way of press statements, harsh articles in its mouthpiece Global Times, and warning India of unfair trade practices. Then it decided to shift the scene to under dispute but almost settled Sino-Indian Border. Two of the three incursion points chosen had traditionally been undisputed in the past. China once again dared India but knew very well that it was not the same India of 1962. It was trying its usual technique of messaging and signalling to coerce India least realising that India had learnt its lessons well at Doklam. China’s recent provocations on the LAC have strategic messaging rather than tactical. These are not usual summertime intrusions. Point to note is that intrusions are almost simultaneous. Naku La in North Sikkim, Galwan Valley in Sub Sector North (SSN) and Pangong Tso (PTSO) in Middle Sector of Eastern Ladakh, the scuffles had very little to do with border dispute because both Naku La and Galwan were never disputed by the Chinese earlier. It wanted to send signals to India that it wants negotiations with maybe the ulterior motive of a compromise ultimately to get out of the global entangle in which China finds itself enmeshed, leverage against the global pandemic enquiry. China is scared of losing its status as ‘global factory.’ China has also tried to provoke Nepal by asking it to raise a boundary dispute with India in the Lipulekh and Kalapani sectors. China is using Nepal as a pressure point as part of its coercive strategy.

While the incursion in North Sikkim was resolved using the existing border management protocols, but the same have failed to resolve the tension in Eastern Ladakh. In fact, China is reported to be strengthening its positions and also some movement has been reported opposite Demchock in Sub Sector South (SSS). As mentioned earlier Chinese action doesn’t appear to be tactical and has geo-political intent. The geo-political dimensions of the conflict have been discussed in the preceding paragraphs. The tactical dimension revolves around China’s assertive and coercive policies to maintain dominance over the adversaries in the areas of conflict.

As part of its War Zone Concept (WZC) doctrine, China has rapidly developed infrastructure right up to the forward posts to create military asymmetry to gain an advantage over the adversary in a short or localised conflict. However, it objects strongly and reacts with force to India’s attempt to do the same on its side of the LAC. In the current scenario also the bone of contention is the newly constructed Leh-Shyok-DBO Highway which has not only removed the asymmetry but placed Indian troops in advantage. Coupled with this is the activation of a number of ALGs activated by the IAF. The Chinese sensitivities in the area lie in Aksai Chin and Karakoram pass, both of which have become easily accessible to the Indian troops.

That is the reason the Chinese side is focusing on the Galwan stand-off, painting India as the aggressor. In an article, its official Global Times newspaper accused Indian troops of crossing over into Chinese territory and swore to protect their sovereignty. In typical Chinese style, they predicted India would regret its actions, “the Galwan Valley is not like Doklam because it is in the Aksai Chin region in southern Xinjiang of China, where the Chinese military has an advantage and mature infrastructure. So, if India escalates the friction, the Indian military force could pay a heavy price.”

To understand the Chinese belligerence, one needs to understand the PLA. Unlike the IA, PLA is not a national army. It is the military wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) with the primary role of ensuring the supremacy of the CCP. Unlike a national army dedicated to the defence of a state and its people, the Chinese military’s purpose is to create political power for the party. PLA is guided by the “political warfare” doctrine of the CCP which includes “Three Warfares” or “3Ws” encompassing, public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare. The first of the “3Ws,” media or public opinion warfare, attempts to shape public opinion both domestically and internationally. If the domestic element sounds odd, it is because the PLA believes energising or mobilising the Chinese public is useful for signalling resolve and deterring foreign incursions on Chinese interests. The second warfare attempts to influence foreign decision-makers and how they approach China policy. The third seeks to shape the legal context for Chinese actions, including building the legal justification for Beijing’s actions and using domestic laws to signal Chinese intentions. All of these fall under the broader umbrella of political warfare. The party leads PLA follows. It would be of interest to note that both Doklam and the current stand-off was synchronised with the important political meetings of the CCP which are held periodically to critically examine the efficacy of the government, Xi Jinping in the instant case.

Exaggerated figures of troop deployment, pitching of dummy tents, deployment of heavy machinery, verbal aggression, propaganda, no holds barred hate campaign, threatening statements through state-controlled media, cyber-attacks, misquoting laws and interpreting to its advantage are all the tricks of the trade employed by China. India understands the Chinese brinkmanship very well. India’s stand till now has been not only politically and militarily correct but aggressive as well. China also understands that its international image is at the lowest in the contemporary era. It would not be able to browbeat India so easily

The military strategy of the PLA is based on the famous concept of “winning without fighting.” Even today CCP believes in the famous quote of Sun Tzu, “To win a hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” Coercion remains the basic philosophy for resolving political differences. In military terms, it’s called “shi”, calibrated power display with limited forces on the borders to seek sino-centric solutions. China believes in coercing the adversaries to submit to its will or face the consequences. Psychological Warfare (Psy W) is an important component of Chinese warfighting doctrine. It also believes in creating adverse political pressure through a disturbing neighbourhood. Nepal’s recent hostile attitude and Pakistan are the two examples of the same. Another terminology often used to explain Chinese war-fighting doctrine is Unrestricted Warfare. The ultimate aim is to secure victory over the adversary through aggression and coercion without the need to fight a war.

Exaggerated figures of troop deployment, pitching of dummy tents, deployment of heavy machinery, verbal aggression, propaganda, no holds-barred hate campaign, threatening statements through state-controlled media, cyber-attacks, misquoting laws and interpreting to its advantage are all the tricks of the trade employed by China.

India understands the Chinese brinkmanship very well. India’s stand till now has been not only politically and militarily correct but aggressive as well. China also understands that its international image is at the lowest today. It would not be able to browbeat India so easily. China is scared that with the changed military equation in the sector, India may not become aggressive about Aksai Chin like it has done in the case of Gilgit-Baltistan. In geo-strategic terms, China today has many vulnerabilities like Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, Xinjiang, South China Sea, to name a few. India has strengthened its position not only militarily but strategically as well. Therefore, India needs to stand firmly and retain its control over the LAC. The dragon has made a mistake this time by daring India. India’s dominant location in the Indo-Pacific bestows upon it a strategic advantage. Both sides need to negotiate an exit strategy and beleaguered China if thinking to use this as a bargaining strategy to strengthen the geo-political image of CCP at home may have to concede more than India. The best way to face the dragon is to tame it. That is exactly what India is doing. Proverbial Chinese dragon is supposed to be peaceful, unlike its western fire-spitting version.

(The writer is a Jammu based veteran, political commentator, columnist, security and strategic analyst. The views expressed are entirely personal)

Comments