Dindigul: The concept of toll collection, a cornerstone of modern infrastructure funding, has its roots in ancient practices, as revealed by recent discoveries of stone inscriptions in Tamil Nadu. These inscriptions, dating back to the 14th and 17th centuries, provide valuable insights into the sophisticated systems of taxation and toll management employed centuries ago.

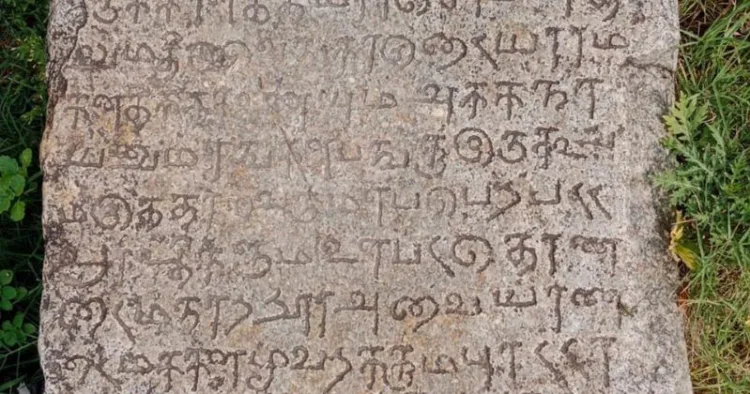

One such discovery, found in Andipatti Kottai on the ancient Grand Trunk Road, sheds light on a 17th-century toll gate system. A flagstone bearing an inscription dating back to 1701 AD details the appointment of an individual to operate a toll gate and safeguard traders passing through the Rengamalai Pass. The inscription, studied by the Dindigul History Research Committee and coordinated by historian N.T. Viswanathadass alongside students Rathinamuralithar, Chandrasekar, and Uma Maheswaran, also features a relief sculpture of Lord Ganesha.

The inscription recounts the philanthropic efforts of Vellaippan, son of Chinna Karupur Kunjaga Gounder, during the administration of Kuma Bommai Naicker, son of Periya Thambi Naicker. Vellaippan constructed a choultry (rest house) in the village square and dug a pond for the benefit of villagers and traders. In recognition of his contributions, Vellaippan was granted the right to collect a toll of one kasu (coin) per bullock cart. The funds collected were also designated for maintaining the village pond, ensuring a sustainable ecosystem for the community.

The inscription warns against disrupting Vellaippan’s duties, invoking a severe curse akin to committing grievous sins such as killing a cow on the Ganga’s banks or harming one’s parents. The traders, primarily from Vedasandur, traversed the Rengamalai Pass en route to Karur, underscoring the Grand Trunk Road’s historical significance as a commercial artery.

Insights from the 14th Century

In a related discovery, an inscription from Verayur dating back to the 14th century was deciphered as a proclamation of tax exemptions granted to Kaikkolars, a weaving community. Archaeology enthusiast S. Balamurugan, informed by teacher Neethidoss, visited the site and documented the find.

Further, an inscription near Thondi in Ramanathapuram district reveals insights into land tax practices during the reign of Sri Parakrama Pandiyan (1315–1334 AD). Found during renovation work at the Uthipootha Perumal Temple, the inscription mentions the temple deity, Puravuvari Vinnakara Peruyan, where Puravuvari refers to land tax. This stone carving, dated to 1329 AD, highlights the integration of taxation systems into temple administration and community life.

These findings underline the continuity of toll collection as an economic mechanism, deeply rooted in the Indian subcontinent’s history. Unlike modern toll systems that sometimes face public resistance, ancient communities appeared to embrace such practices, recognizing their role in sustaining infrastructure and community welfare.

According to the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), the Chola monarchs exercised meticulous control over state resources, including finances. Taxation was overseen by the Variyam (revenue committee), which levied taxes based on Hindu law as prescribed by the Manusmriti. The guiding principle emphasized minimal burden on the populace while ensuring sufficient revenue for public services, royal maintenance, and governance.

The inscriptions reportedly record details of tax assessments and land transactions, highlighting the systematic approach of the Cholas toward governance. Scholars believe these findings reaffirm the dynasty’s commitment to balancing state needs with public welfare.

This discovery offers valuable insight into India’s ancient administrative systems and underscores the need for continued exploration of such historical treasures.

The Ramanathapuram Archaeological Research Foundation has appealed to the government to restore a 300-year-old choultry at Maraiyur near Narikudi, urging its preservation as a heritage monument. The choultry, a symbol of the region’s architectural excellence, was historically a resting place for pilgrims undertaking the sacred “Sethu Yatra” to Dhanushkodi and Rameswaram.

Historical records and media reports suggest that the choultries in Maraiyur and Narikudi were constructed during the reign of Rani Mangammal, who ruled Madurai from 1689 to 1706 AD. Prominent patrons such as the Madurai Nayaks, Sethupathi kings of Ramanathapuram, and Marudhu Pandiyars contributed to these structures. Over time, the Maraiyur choultry served as a school for about 50 years until part of its roof collapsed, leaving it abandoned.

The east-facing choultry features a large mandapam with verandahs and intricate sculptures, including a depiction of Gajalakshmi above the entrance. The mandapam, supported by 49 stone pillars in symmetrical rows, includes relief carvings of Vishnu, flowers, and serpents. The floor is embedded with granite stones, while the structure uses brick and lime mortar.

According to V. Rajaguru, president of the Ramanathapuram Archaeological Research Foundation, the choultry was also renovated by the Marudhu Pandiyars, with additional pillars erected and sculptures donated. Unfortunately, the sculpture of “Periya Marudhu” has been damaged, emphasising the urgent need for preservation.

“This heritage structure represents excellent craftsmanship and requires immediate attention to prevent further degradation. Its restoration can bring recognition to the historical significance of the region,” Rajaguru stated.

He said ” these rooms may have been the kitchen, choultry keeper’s accommodation and store rooms.”From these sculptures we come to know that the ‘Marudhu Pandiars’ renovated the Narikudi choultry and donated it. Similarly, the choultry in Maraiyur was also repaired, renovated and new pillars were erected. Presently, the sculpture of the ‘Periya Marudhu’ has been damaged.

Toll plaza used by the Pandya empires in the 12th century AD to collect taxes was discovered near NPR college in Natham, Dindigul district. This route was used to transport maritime items from the east coast ports of Thondi and Korkai as well as luxury goods made in the Chettinad region to Kongunadu, including the modern-day Palani, Karur, and Coimbatore.

Comments