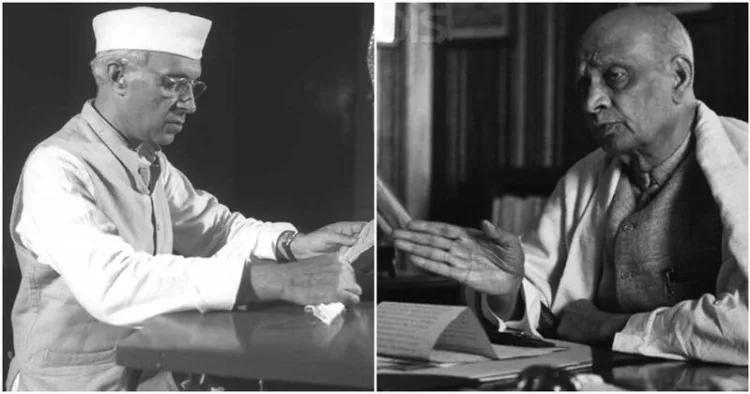

History often unveils its most profound insights not through grand proclamations but through the quiet reflections recorded in personal diaries. One such insight is found in Inside Story of Sardar Patel: The Diary of Maniben Patel (1936–1950), a primary source that documents private political discussions at the highest levels of India’s early leadership. According to Maniben’s diary, Jawaharlal Nehru proposed using government funds to rebuild the Babri Masjid, a suggestion that Sardar Patel firmly rejected. These entries, meticulously noted by Maniben and later published, are significant not for their potential political sensationalism but for the light they shed on the contrasting philosophies of two of India’s foremost leaders during its formative years.

Maniben’s diary entry from September 20, 1950, records a conversation in which Nehru raised the Babri Masjid issue with Sardar Patel, apparently expecting that the government could undertake the project and allocate public funds for the mosque’s reconstruction. Patel, however, responded unequivocally, stating that public money could not be used for the construction of any place of worship. This exchange, as documented by Maniben, highlights a moment when two contrasting approaches to public policy became evident. Patel’s response underscored his steadfast commitment to the state’s neutrality in religious matters, affirming that government expenditure must not favour any religious institution.

The significance of this historical note becomes even clearer when viewed alongside Maniben’s diary entry on the Somnath Temple restoration. According to her account, Patel explained to Nehru that the reconstruction of Somnath was not funded by government money. Instead, it was managed by a public trust specifically established for the purpose. Patel noted that nearly thirty lakh rupees had already been raised through voluntary contributions, and that the trust had a formal structure with a chairman and members, including K M Munshi. In this way, the government carried no financial burden for the project. As recorded in the diary, Patel’s explanation effectively brought the discussion to a close.

The significance of these diary entries lies not in framing historical figures as opponents but in revealing the nuanced choices and differing ideologies that shaped India’s early leadership. Maniben’s records depict Patel as deeply committed to restoring stability and upholding clear governance principles in the aftermath of Partition. His diary consistently emphasises administrative discipline, national unity, and institutional clarity. By contrast, Nehru’s approach, as reflected in this particular entry, appears guided by his belief in fostering communal harmony, even if it meant considering government involvement in matters touching on religious institutions.

Maniben’s diary entry becomes especially striking when considered within the broader context of 1950. India was still grappling with the aftermath of Partition, massive displacement, communal tensions, and the challenges of constitutional reorganisation. Decisions made at the central level carried profound consequences, not only for governance but also for the symbolic direction of the new republic. The question of whether government funds could be used for religious reconstruction was far from a technical matter; it was a philosophical issue with lasting implications for the nation’s identity. Patel’s firm refusal, as recorded by Maniben, thus underscores a commitment to a clear separation between state authority and religious restoration.

Equally significant is that these details come directly from a primary personal diary maintained by Patel’s daughter. They are contemporaneous notes by someone who closely observed these leaders’ work and conversations, not retrospective claims or political reinterpretations. While diaries are inherently subjective, they provide an invaluable window into private political interactions that official records often omit. Published diaries allow historians and readers to understand how senior leaders discussed and navigated disagreements behind closed doors.

The inclusion of this entry in a published historical document situates it within the scholarly discourse on India’s early leadership. It illuminates a pattern long noted by historians: the contrast between Nehru’s diplomacy-driven political instincts and Patel’s pragmatic administrative approach. The entry does not demand that readers adopt a partisan view; rather, it invites reflection on how two foundational leaders approached governance differently and how those differences shaped policy debates during India’s earliest years of self-rule.

The resurfacing of such primary sources also reminds us that historical narratives are often shaped as much by what is omitted as by what is emphasised. Public memory has tended to portray Nehru and Patel as a united leadership with shared goals. Yet diaries like Maniben’s reveal that disagreements over principle were common and consequential, forming an essential part of understanding the foundations of India’s political and administrative structures.

The most responsible way to approach this diary entry is to take it at face value: as a personal record by a contemporary observer, offering insight into a conversation between two central figures. It does not require embellishment or reinterpretation, only careful attention as a historical source. In doing so, readers gain a clearer view of the interplay of ideas, priorities, and philosophies that shaped early independent India.

Ultimately, the central point remains clear. According to Maniben’s diary, Nehru proposed using public funds to rebuild the Babri Masjid, while Patel rejected the idea, insisting that government money must not support religious projects. Preserved in writing, this moment invites renewed reflection on how India’s early leaders understood the relationship between state authority and religious life. It also demonstrates the enduring value of primary sources in revealing layered truths that often lie dormant until readers engage with them directly.

Comments