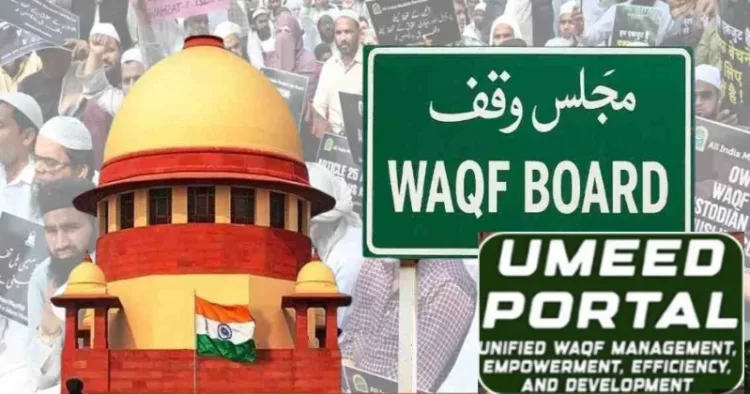

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court on December 1 refused to extend the six-month statutory deadline for registering Waqf properties under the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025 effectively placing responsibility back on Waqf Boards whose chronic administrative failures have delayed digitisation for over a decade.

A Bench of Justice Dipankar Datta and Justice Augustine George Masih made it clear that applicants seeking extra time must approach the Waqf Tribunal, not the apex court. The deadline for online registration, which ends on December 6, now remains unchanged.

“Since a remedy for the applicants is already available before the Waqf Tribunal, they may seek the same by December 6,” the Bench said, emphasising that Section 3B already lays down clear procedures for extensions in specific cases.

The Court also noted that technical failures or procedural roadblocks can be raised before the Tribunal, which is empowered to grant relief on a case-by-case basis. While several senior advocates Kapil Sibal, AM Singhvi, Nizam Pasha, and MR Shamshad argued that the UMEED digital portal was riddled with glitches, the deeper issue, highlighted repeatedly during the hearing, was the Waqf Boards’ long history of poor record-keeping and slow digitisation.

Kapil Sibal himself admitted:

- “It took 11 years for digitisation to happen.”

- “Rural properties are not digitised.”

- “People have been trying every day they cannot upload.”

These failures have left lakhs of mutawallis and beneficiaries struggling at the last moment, as Boards failed to modernise even basic records despite repeated directives over the years.

Senior Advocate MR Shamshad pointed out that Waqf Boards already possess the details of registered properties—yet their outdated systems and fragmented documentation make uploading to the portal nearly impossible at scale.

The Boards’ inability to:

- update records

- map properties

- verify boundaries

- track leases

- identify mutawallis

- has now resulted in a massive administrative logjam.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta countered the petitioners’ arguments by stressing that Waqf property registration is nearly a century-old requirement, and Boards have had ample time decades, in fact to build proper records.

He argued that the applicants were essentially asking the Court to override a statutory deadline because Waqf Boards had failed to do their job for years.

When asked how many properties had been registered so far, petitioners admitted the number hovered around 10 per cent, highlighting a severe lack of preparedness despite the long-standing legal obligation and the six-month window provided by the amended law.

Yet, the Supreme Court refused to intervene without proof of large-scale portal malfunction, stating, “If the portal is functional which the solicitor says and you dispute, you have to give some proof.”

Kapil Sibal warned that forcing each mutawalli to approach the tribunal individually would overwhelm the system. But the Court was unsympathetic, observing, “The tribunal will decide on a case-to-case basis. If it takes time, it is an advantage for you.”

This response underscores a larger issue, Waqf Boards’ inefficiency has now pushed lakhs of stakeholders into emergency legal routes, clogging tribunals that will be forced to handle avoidable applications applications that would have been unnecessary had Boards digitised their records years ago.

The Supreme Court had already refused to stay the mandatory registration requirement in September, noting that registration existed under older versions of the law as well. The current crisis, therefore, reflects institutional negligence, not sudden regulatory pressure.

The UMEED portal with geo-tagging, GIS mapping, digital inventories, and public transparency tools was meant to end decades of opaque and mismanaged Waqf administration. Instead, Boards’ failure to prepare has turned implementation into a last-minute scramble.

Comments