Bharat stands today at the threshold of a profound transformation in its labour landscape. The enactment of the four Labour Codes marks one of the most far-reaching reforms since Independence. Together, these four codes do not merely rationalise and consolidate old laws; they redefine the nation’s commitment to dignity, justice, and welfare for every worker. They represent a civilisational leap forward, reaffirming that a nation’s true strength lies in the well-being of its labouring millions.

Great Leap Towards Antyodaya

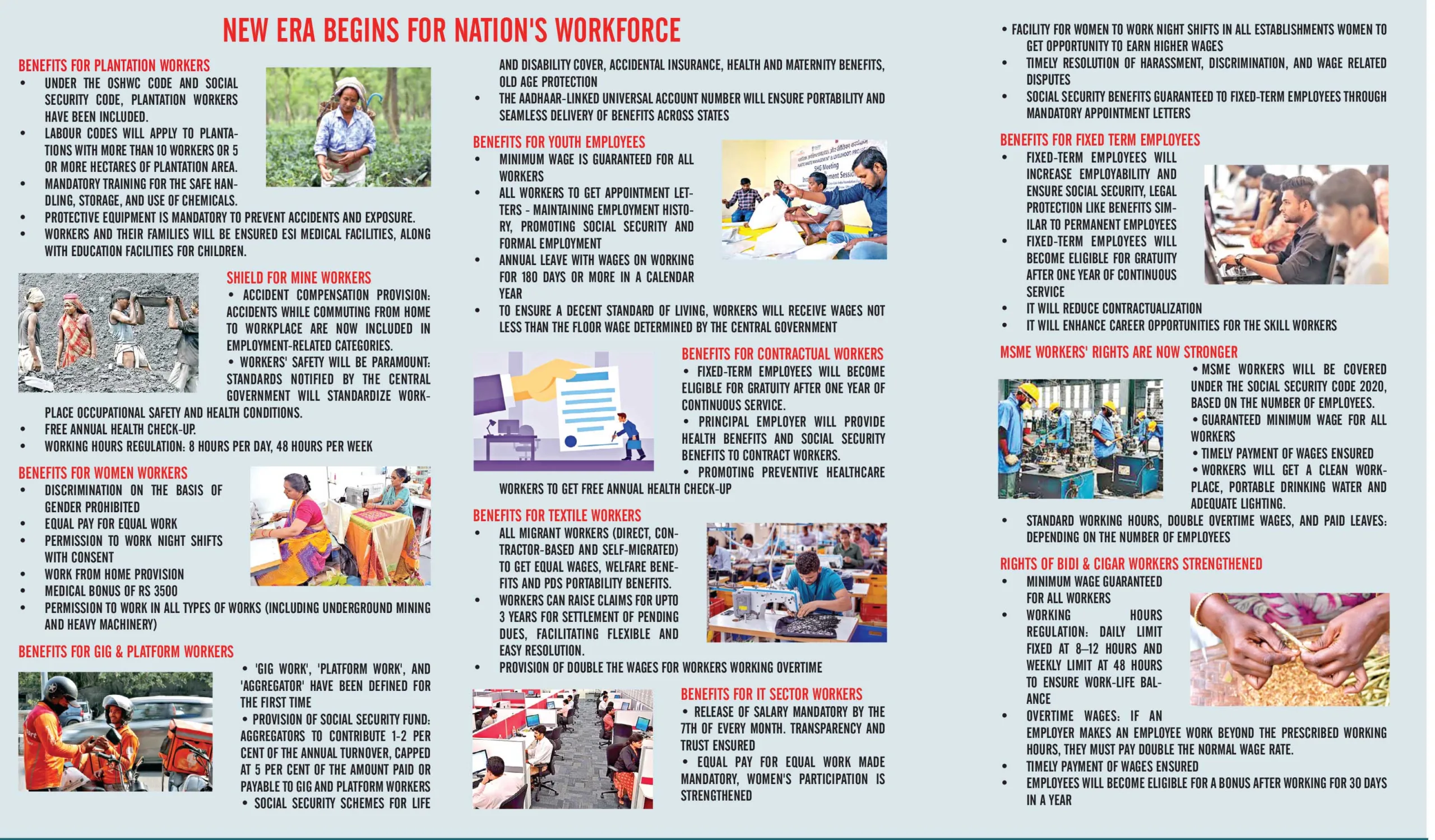

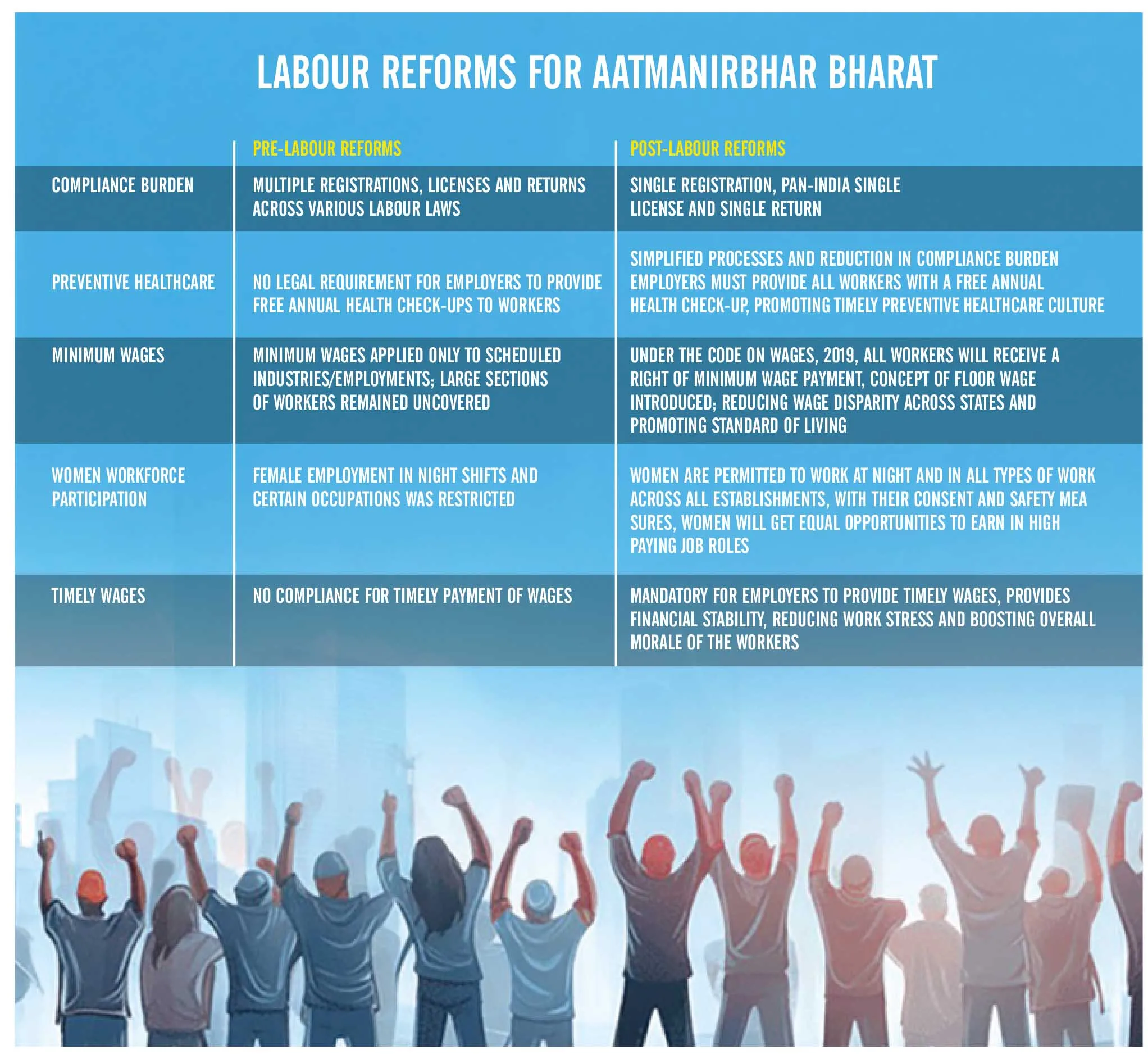

For the first time in 78 years after Independence, Bharat has achieved the universalisation of minimum wages. The last worker in the most remote corner of the country now enjoys a legal and enforceable right to a minimum wage. The inequities and inconsistencies that plagued the earlier regime, such as the limited application of minimum wages only to a few scheduled sectors, the existence of different wage rates for different industries, and even disparities within the same sector for similar work, have all been decisively eliminated.

The code mandates a compulsory revision of minimum wages within five years, ensuring that wages keep pace with changing economic realities. It completely prohibits gender discrimination, not only in the payment of equal remuneration but also in recruitment and in every condition of employment. The introduces transparency by requiring that wages be paid through banking channels. It empowers not only inspectors but also the workers and their trade unions, by granting them the right to file criminal complaints in cases of violation. It further extends the permissible period for filing wage claims from the present six months to three years, thereby enhancing the worker’s prospects of securing justice.

The assurance of minimum wages will enhance the average purchasing power of the common citizen, which in turn will invigorate markets and stimulate the manufacturing sector. This will lead to higher remuneration for workers, thereby completing a virtuous cycle of ‘wage-led growth’.

Emergence of World’s Largest Social Security System

The Code on Social Security represents an equally path-breaking reform by extending its shield to every segment of Bharat’s diverse workforce. Earlier, the Employees’ State Insurance (ESI) and Employees Provident Fund (EPF) schemes applied only to select areas specified in the schedules appended to their respective Acts. The removal of these schedules marks the first decisive step for the ESI and EPF in their journey toward reaching the last worker. The Employees’ State Insurance scheme has now been extended to any hazardous occupation, even where only a single worker is employed. It is also applicable to every establishment with ten or more workers, and has been extended across the entire geographical expanse of India, whereas earlier it applied only to the 565 fully notified districts and 103 partially notified districts. Mine workers, who had previously been excluded, are now explicitly brought within its fold. The Code ensures that even if the employer fails to enrol the worker, register the establishment, or pay the required contribution, the employee shall remain entitled to the full range of ESI benefits.

The Employees’ Provident Fund, Employees’ Pension Scheme, and the Employees’ Deposit Linked Insurance Scheme now apply uniformly to all establishments employing 20 or more workers. Social security enrolment has been decentralised through “workers’ facilitation centres” at lower levels. This will help address the inadequacy of the labour department’s limited strength in handling the vast working population that will now come under the beneficial protection of the Labour Codes. Compensation is assured for accidents occurring while travelling to and from the workplace, thereby settling the legal ambiguity that once surrounded such situations.

The entire unorganised sector is now brought under the umbrella of a social security scheme endowed with twelve enhanced benefits, along with six benefits for gig and platform workers. The Code embraces the changing nature of work by explicitly covering gig workers, online platform workers, interstate migrants, home-based workers, domestic workers, and fixed-term employees. It holds the principal employer responsible if a contractor fails to pay the social security contributions of contract workers. For migrant workers, the creation of Aadhaar-linked social security numbers ensures portability of benefits across states. The Code further provides the benefit of gratuity even to those engaged for less than five years, in the case of fixed-term employment.

It also mandates that every worker must be given a formal appointment letter, thereby ending informal employment arrangements that denied workers their identity as workers and basic rights. It provides for the compulsory registration of all establishments, regardless of the number of workers engaged.

Global Standards on Safety and Health

The Occupational Safety, Health & Working Conditions Code places human safety and dignity at the very heart of the industrial ecosystem, aligning India with global standards of workplace safety and health. It requires all establishments employing more than ten workers to comply with safety and health provisions. It grants every employee the right to obtain information on workplace dangers and the right to report such hazards to the inspector without fear of reprisal. It also affirms the employee’s right to periodic medical check-ups to strengthen preventive health care.

From Conflict to Confluence

The Industrial Relations Code signifies a philosophical shift from conflict to collaboration. The very adoption of the name “Industrial Relations Code” in place of the old “Industrial Disputes Act” reflects a new vision founded upon dialogue and harmony. The Code restricts the retention of badli workers only to one year. It introduces a new chapter on ‘Bi-partite Forums’, to resolve floor-level disputes through direct dialogue between the worker and the employer, instead of compelling them to run to the labour department for every grievance. Conciliation officers are entrusted with the authority to enforce the attendance of both parties during conciliation proceedings. Henceforth, the conciliation process shall no longer fail on account of the parties’ non-attendance. Failure reports from conciliation are now sent directly to the parties concerned, replacing the outdated colonial-era practice of routing matters through the government. When conciliation fails, parties may directly approach the Industrial Tribunal without awaiting a governmental reference. Awards of the Tribunal are communicated directly to the parties, ending the colonial practice of publication in the Gazette. The earlier bifurcation between Labour Courts and Industrial Tribunals has been done away with; under the new Code, both stand merged as a single Industrial Tribunal. The Code introduces provisions for the recognition of Central and State Trade Unions; it also vests the Tribunal with the power to grant interim relief.

The Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh placed twelve significant concerns before the Government regarding the Industrial Relations Code and another twelve regarding the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code. Many such measures affecting mostly the organised sector have already been implemented by several State Governments under the banner of attracting investment. Union Labour Minister assured the BMS delegation that the Government would take due cognisance of these issues and ensure that they are addressed.

The Historic moment

The BMS has characterised the two codes, on Wages and on Social Security, as both historic and revolutionary, for they promise not merely the elevation of workers’ living standards but also the strengthening of the nation’s very economic foundations. They mark a watershed moment in the history of labour reforms in India. Now the Himalayan task remains: carrying this historic transformation to the last worker in the country. India’s working population today exceeds five hundred million, and reaching each one of them demands a concerted national effort. Trade unions, employers’ organisations, and the Government must work in close partnership, while other social organisations, too, must assume their share of responsibility; for upon this collective resolve rests the promise of a true national resurgence.

Comments