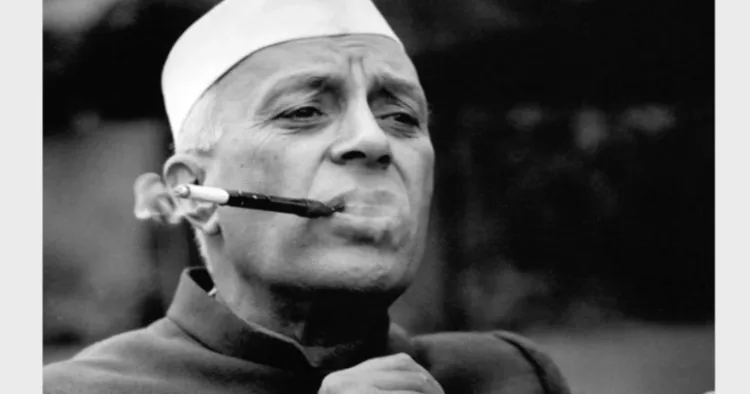

For decades, Indians have been fed a sanitised narrative about why November 14 is celebrated as Children’s Day. Textbooks, public speeches, and school functions repeat the same line: Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru “loved children,” was fondly called Chacha Nehru, and once famously said, “The children of today will make the India of tomorrow.” According to this popular version, the nation unanimously chose to honour Nehru after his death in 1964 by marking his birth anniversary as Children’s Day.

But the historical record tells a very different, sharply uncomfortable story.

Contrary to the widely circulated belief, Nehru Jayanti was not declared Children’s Day after Nehru’s demise. Reports, archives, and newspaper records point to something startling: Nehru’s birthday was first celebrated as Children’s Day in 1955 while Nehru himself was Prime Minister.

And what prompted this decision?

Not child welfare. Not affection for the nation’s young. Not even public demand.

According to available documents, the 1955 declaration was a political public relations exercise crafted to impress Soviet leaders Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev, who were visiting India at the time. The entire event was designed to project Nehru as a mass leader adored by children—much like the Soviet propaganda cults that revolved around personality glorification.

The earliest and most scathing critique came from Organiser Weekly, in its November 21, 1955 edition. Senior journalist and editor K R Malkani penned a blistering editorial, drawing parallels between Nehru’s tactics and Adolf Hitler’s use of the “Hitler Youth” for building authoritarian control.

Malkani noted, “Preparations to celebrate Pt. Nehru’s birthday and the Russian leaders’ arrival have set us thinking… We must confess that the above preparations remind us of the ‘Hitler Jugend’.”

The editorial highlighted a disturbing truth: Delhi’s school system had been paralysed for three weeks as thousands of students were forced to rehearse for orchestrated birthday celebrations.

According to the editorial:

- Students from almost every class were pulled out daily for hours-long rehearsals

- Normal teaching came to a halt

- Truckloads of children boys and girls were transported daily to the Qutub Minar grounds.

- Children were trained in drilling, marching, smiling, waving, garlanding, and shouting slogans on cue

The justification? “Observing Children’s Day.” Malkani’s biting response remains relevant even today, “Wasting children’s education for three weeks is a rather wonderful way of celebrating Children’s Day.”

He questioned the very basis of choosing Nehru’s birthday, “Nor is it clear why Pt. Nehru’s birthday should have been particularly selected for observation as Children’s Day.”

The editorial further argued that if any dignitary’s birthday deserved national celebration, it should have been the President of India not the sitting Prime Minister proclaiming his own birth anniversary as a national festival.

K R Malkani warned, presciently, “Is it the idea that ‘Nehru Jayanti’ should be observed as Children’s Day forever hereafter? Or does Children’s Day change with every incoming Premier’s birthday?”

Nehru ensured his birthday would permanently remain Children’s Day, cementing his personal cult in the national psyche. Interestingly, the editorial suggested a culturally rooted alternative, “The right day for Children’s Day would be Krishna Janmashtami the birthday of the great child of all times, Sri Bala Krishna.” But this suggestion was, unsurprisingly, sidelined in favour of Nehru-centric observances.

A year later, on November 14, 1956, The Times of India reported, “Nearly 100,000 children assembled at the National Stadium today to participate in a Children’s Day rally, which coincided with the Prime Minister’s 67th birthday celebrations.”

This single line confirmed the reality, Children’s Day was simply Nehru’s birthday celebration, copied straight from Soviet-style mass rallies and cloaked in the rhetoric of children’s welfare.

Ironically, Nehru had warned in Discovery of India about “invisible colonialism” the dangers of subtle domination through ideas and narratives. Yet, the 1955 decision to force children into political propaganda was itself an example of cultural colonisation not by foreign powers, but by a ruling elite eager to project imported Soviet-style theatrics onto Indian soil.

The myth that Chacha Nehru’s affection for children birthed Children’s Day has persisted for seven decades, unchallenged in textbooks and public discourse. But with archival evidence and contemporary reports resurfacing, it is time to revisit and rectify the narrative.

Children’s Day should be about children, not political symbolism. It should honour childhood, not a Prime Minister’s carefully crafted image. And it must be rooted in India’s cultural ethos, not in Cold War-era personality cults.

Why do we celebrate Nehru Jayanti as Children’s Day?

The answer long buried beneath rosy anecdotes is finally emerging, Because Nehru himself declared it so, for political theatrics, not for children. It is time for India to re-examine this legacy with facts, not folklore.

Comments