While the world debates the mutilation of the headless Bhagwan Vishnu murti at Khajuraho, a far graver and more recent cultural tragedy is unfolding quietly at Garhwa Fort in Prayagraj. Unlike Khajuraho’s Javari murti, which was vandalised centuries ago, the murtis at Garhwa were largely intact until just a few decades ago. Photographs and archaeological studies confirm that these masterpieces of devotion and art have suffered systematic vandalism, theft, and neglect in recent times.

Archaeologists, studying Garhwa since 2022, have revealed the scale of destruction at what was once an important Vaishnavite hub dating back to Gupta times. Today, the site’s ruined mandirs, defaced murtis, and scattered inscriptions stand as silent witnesses to the site’s long and turbulent history.

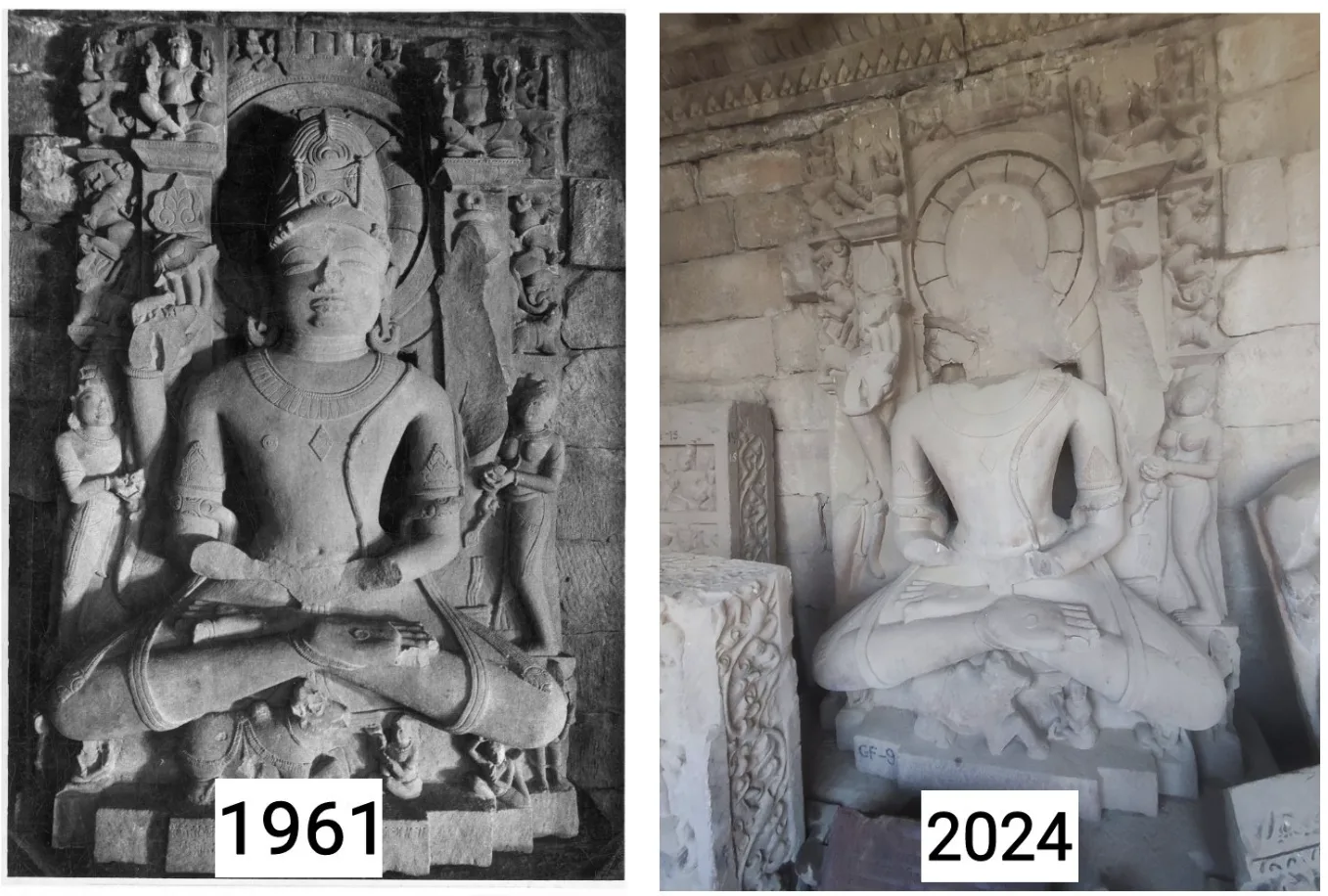

Among the most poignant victims is a colossal seated Shiva murti from the late 9th to early 10th century CE. A black-and-white photograph taken in 1961 shows the head intact; today, it is missing. The damage at Garhwa is not limited to Shiva alone. The site once housed a remarkable set of Dashavatara sculptures from the 11th century CE, now largely defaced.

The Matsya (fish) avatar sculpture, once flanked by the four Veda Purushas, has all four figures mutilated. The Vamana (dwarf) avatar now stands headless. Narasimha, Rama, Parashurama, Kurma, and Varaha murtis have all suffered damage. Even the sculpted images of the mandir’s founders Ṭhakkura Raṇa Pāla, a Srivastava Kayastha, and Chakkura Gaguka, a Brahmin etched on the pillars with inscriptions, have been defaced.

Vandalism at Garhwa is compounded by a history of theft and violence. In 2002, an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) employee, Vinod Srivastava, was murdered while investigating the site. During the attack, a massive 7–8 feet Buddha avatar of Bhagwan Vishnu was stolen. This life-sized murti, one of the largest representations of Buddha as Bhagwan Vishnu, has never been recovered. The culprits remain at large. This incident highlights the vulnerability of Garhwa to organized smuggling networks and underscores the lack of effective law enforcement over decades.

The Bhagwan Vishnu shrine at Garhwa is historically significant. Archaeological evidence traces the site back to the Gupta period, with inscriptions recording contributions of several Gupta emperors. The existing mandir was erected in 1199 Vikrama Samvat (1142 CE) by Thakkura Raṇa Pāla. The mandir pillars record salutations from other Kayastha dignitaries of the period, such as Sri Sakasena (Saxena) Kayastha Mahidhara, highlighting Garhwa’s administrative and cultural importance.

The mandir’s Garbha Griha once housed a colossal Sheshashayi Vishnu murti, surrounded by representations of Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Rama, Parashurama, and Vamana. These monumental sculptures provided a rare and comprehensive visual record of Bhagwan Vishnu’s avatars in medieval India—a heritage now severely compromised.

Recent archaeological explorations unearthed ruins beneath a wild fig tree in the north-western corner of Garhwa Fort. Scholars suggest that these ruins correspond to the earliest known Ram mandir mentioned in a local inscription of Kirttivarman Chandela from Vikrama Samvat 1152.

The inscription, recently translated by Shri Kushagra Aniket and Dr Shankar Rajaraman, notes that the mandir was constructed over an earlier ashrama of Shri Rama. This aligns with the Valmiki Ramayana, which states that Rama, along with Lakshmana and Sita, spent a night at Shringaverapura before crossing the Yamuna en route to Chitrakoot:

“विहृत्य ते बर्हिणपूगनादिते शुभे वने वानरवारणायुते।

समं नदीवप्रमुपेत्य सम्मतं निवासमाजग्मुरदीनदर्शनाः॥”

This discovery reinforces Garhwa’s significance as a historical and religious landmark connecting the epic narrative of the Ramayana with tangible archaeological evidence.

Adding to Garhwa’s historical depth, a previously unpublished 11th-century Chandela inscription was recently discovered on a large red sandstone slab. Issued by Vatsaraja, a Srivastava Kayastha minister of King Kirttivarman Chandela, the inscription records the construction of a Rama mandir in Allahabad and provides detailed eulogies of three Chandela kings Vidyadhara, Vijayapala, and Kirttivarman.

Vatsaraja is described as the crest-jewel of the Vastavya lineage, serving as Sandhi-Vigrahika the Minister of Peace and War. Historically, this office combined military command with diplomatic authority and was often held by Kayasthas from Rajasthan to Odisha. This record is only the third known reference to a Chandela-era Sandhi-Vigrahika and underscores the administrative prominence of Kayasthas in medieval Hindu kingdoms.

The inscription also records Kirttivarman’s victory over the Kalachuri king Karna and highlights Vatsaraja’s earlier achievements, including his involvement in the construction of forts and ghats. This adds a crucial political and historical dimension to Garhwa, revealing it as both a religious and strategic site.

Despite its immense heritage, Garhwa has been largely ignored by authorities. Decades of lawlessness, compounded by smuggling and vandalism, have left the site in a fragile state. The 2002 murder of an ASI employee and the theft of the colossal Buddha avatar exemplify the risks associated with neglect.

Recent efforts at fort renovation and improved administration offer hope, yet the scars of vandalism remain visible. Archaeologists and historians emphasise that without urgent and sustained intervention, Garhwa risks losing its remaining heritage. This would mean the permanent erasure of not just physical monuments but centuries of religious, political, and cultural memory.

Comments