Delhi, the heart of India, carries a darker truth; its air has become a carrier of disease. A recent study by the Bose Institute, an autonomous body under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), has revealed alarming findings: airborne pathogens in Delhi’s crowded urban regions are nearly twice as abundant as those in less populated areas. These pathogens or microscopic bacteria are capable of causing respiratory, gut, oral and skin infections, which are a result of the toxic mix of pollution, weather and unchecked urban growth.

For over 25 years, successive governments under Congress (INC) and later Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) have failed to recognise or act decisively on the city’s worsening air and health crisis. Their delays and inaction have now allowed a silent epidemic to grow in the air itself.

How weather and population density fuel the pathogen surge

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, where Delhi is one of the most densely populated regions in India and the world. It is also infamous for its extreme levels of air pollution. Winters bring western disturbances that sharply drop temperatures and raise relative humidity. This weather change creates stagnant winds and lowers the boundary layer of the atmosphere, trapping pollutants close to the ground. This results in a thick, poisonous mix of smog and suspended particles that blankets the capital every winter.

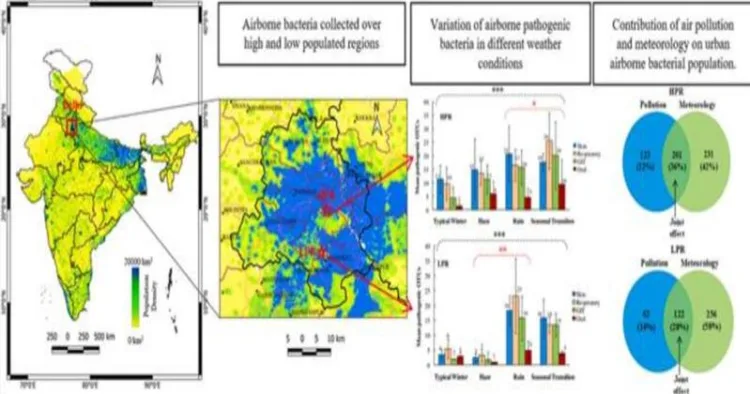

For years, experts have noted spikes in microbial populations during different seasons, but data were scattered. The new study fills this gap by directly linking factors such as meteorology, population density and pollution with the rise of airborne pathogens. It also provides the strongest evidence of how Delhi’s unique environment makes its residents highly vulnerable to airborne diseases.

The Hidden Carriers: PM2.5 particles

The centre of this issue is PM2.5 particles, the small dust motes smaller than the thickness of a human hair. They are hazardous with the ability to reach deep into the lungs and bloodstream. But the Bose Institute study has revealed something even more disturbing that these particles serve as carriers for pathogenic bacteria.

Simply, the PM2.5 particles provide a free ride for bacteria through the city. When inhaled, these particles containing bacteria bypass the body’s own defenses, settling in the lungs and even spreading to the rest of the body. The result has increased the risk of infection from mild bronchitis to pneumonia to stomach ailments and other skin conditions.

The study compared bacterial communities in high-population regions (HPR) with low-population regions (LPR) within Delhi. The results were stark HPR zones had nearly double the presence of airborne pathogens. For millions of people living in such areas, every breath carries an invisible gamble with health.

Scientist Dr. Sanat Kumar Das highlighted a critical detail that the transition from winter to summer, especially during hazy days or after the winter rains, often creates a high-risk window. These are periods when pollution and weather patterns combine to allow microbes to remain suspended in the air longer than the normal time period.

During these weeks, the chances of infections spreading across the population are significantly higher. With Delhi’s immense population density, even a small spike in airborne bacteria can translate into a major public health issue. Yet, this knowledge is new to many policymakers who have long treated air pollution as a problem of visibility and breathlessness but not as a carrier of infectious diseases.

A wake-up call for urban health planning

The findings were published in the international journal Atmospheric Environment. The paper is more than a scientific breakthrough; it is a warning bell. It suggests that Delhi is not only fighting with smog and toxic chemicals, but also people are living with invisible bacterial colonies that thrive in polluted conditions.

For megacities like Delhi, where millions already face chronic respiratory problems, this hidden pathogen is a crisis. By ignoring the biological dimension of pollution, the governments had already underestimated the long-term health hazards. The consequences may soon include outbreaks of infections tied not to water or food but to the air which citizens breathe.

Years of political neglect

The science is new, but the warning signs were not. For over two decades, Delhi has topped global charts as one of the most polluted cities. Congress-led governments at both the state and central levels had repeated opportunities to improve urban planning, upgrade waste management and invest in clean energy sources, but they chose few steps instead of systemic reforms.

According to reports, between 2009 and 2013, approximately Rs 385 crore was collected specifically for Delhi’s air pollution programs over a seven-year period up to 2015; however, 87% of these funds remained unspent.

After 2012, the Aam Aadmi Party, which came to power by promising clean air and better health, also failed to deliver meaningful changes. Despite high-pitched campaigns and publicity drives, there has been little sustained investment in reducing particulate matter or in building public health systems capable of tracking and responding to airborne infections.

From 2015 to November 2021, the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) spent over Rs 470 crore on air quality improvement measures, from 2019-20 to 2023-24, Delhi received Rs 42.69 crore under the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) from the central government, but as per official data, it spent only Rs 13.94 crore about 32.65 per cent of the allotted amount. This pattern of inaction and delay has left Delhi citizens vulnerable. The current research only proves what has long been feared: pollution here is not just an environmental issue, it is a carrier of disease.

The Way Forward: From pollution control to pathogen surveillance

The study by the Bose Institute makes it clear that tackling Delhi pollution cannot be limited to cutting vehicle emissions or stubble burning. Policymakers must recognise this complex pattern between weather, air particulates and bacteria. Urban planning must incorporate microbial surveillance, and public health systems must be prepared for outbreaks linked directly to airborne pathogens.

Funding is also required for awareness campaigns to help citizens understand the risks of pollution beyond coughing and asthma. People need to know that the very air around them can harbour disease-causing bacteria, especially in crowded areas.

The link to the published study (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeaoa.2025.100351) provides a roadmap for scientists and policymakers alike. Mapping pathogen concentrations and identifying the high-risk weather periods will help in the prediction of infection surges before they spread into public health emergencies.

This will only work if governments act decisively. The days of political grandstanding and half-measure implementation must end. Delhi needs long-term, science-backed interventions with better waste management, reduction of PM2.5 sources and integration of health planning into air quality policies. Without this, the city risks becoming a permanent hotspot for airborne infections.

Delhi battles with pollution that is no longer just about the smog-filled sky. Now, it is about the silent spread of bacteria that ride through the air on tiny particles. The Bose Institute study shows that these pathogens are more concentrated in crowded regions, putting millions at risk every single day.

The real tragedy is that this was preventable, but the successive Congress governments and the ruling AAP leadership have failed to act with urgency. Their inaction has allowed the city’s pollution crisis to evolve into a direct health hazard, where infections are not in water or food but in every breath.

Delhi today stands at a crossroads. Either it acknowledges this invisible threat and reforms urban health planning, or it collapses into a future where pollution-fuelled pathogens silently claim lives. The choice is not scientific; it is political, and it is urgent. If the status of Air Pollution in Delhi needs to be improved, then major union government programs like the NCAP funds have to be utilised.

Comments