In the ever-expanding theatre of Indian politics, where the dramatis personae range from the earnestly reformist to the theatrically quixotic, one must reserve a special loge for Rahul Gandhi. In his latest foray into the perilous art of rhetorical excess, Rahul Gandhi has uncorked what he deems an epochal revelation, a jeremiad on what he styles as “Vote Chori”, an alleged wholesale larceny of the franchise that, if true, would amount to nothing less than the defilement of our democratic compact. And yet, like so many of his prior sallies into the realm of high indignation, this latest effusion has proved to be long on declamation and desperately short on substantiation.

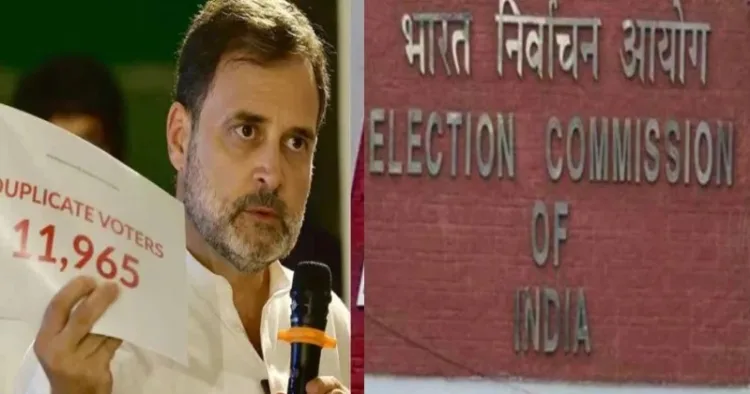

It is a melancholy truth that in a polity as cacophonous as ours, the temptation to convert every electoral reverse into an indictment of the system is almost irresistible. But when a leader purports to have uncovered a conspiracy of such staggering proportions speaking in breathless cadences of one hundred thousand votes pilfered from a single constituency, of ghost voters and counterfeit rolls, of electoral officers in cahoots with the ruling dispensation the citizenry is entitled, nay obliged, to expect that he will furnish proof commensurate with the gravity of the charge. The Election Commission, that venerable custodian of our electoral probity, quite reasonably invited Rahul Gandhi to do precisely that: sign a statutory declaration affirming his claims, submit his evidence for forensic scrutiny, or else retract and apologise to the nation. That he has thus far eschewed this prosaic but indispensable step is the first damning note in this overture of self-inflicted discredit.

For what Rahul Gandhi has offered in lieu of proof is a potpourri of anecdote and innuendo: the tale of an elderly matron, Shakun Rani, allegedly voting twice, which collapsed when the Commission demonstrated she had done no such thing; the accusation that dozens of voters were improbably crammed into a 120-square-foot room, which dissipated when it emerged that the names belonged to transient migrants legitimately registered there; the phantom of double-enrolled voters in multiple states, dispelled by the testimony of state election officers who found only single registrations. Every time, though, the reality stayed stubbornly unhinged from the story he weaved, and yet that story continues to float because in politics it is not truth but traction that gives worth. This is where the Platonic idealism analogy, ironically used by some of his supporters as an applause line, pieces in so neatly. Some concept of pure form, it seems, is what allows Rahul Gandhi to live in a world where his political manner is taken as an axiom and for other people to believe they see things that way too. In this rarefied realm, lack of evidence is not a stumbling block but an irrelevancy; the purity of accusation is all that counts, the moral grandeur in having taken up arms against the wicked, lying deceivers running loose amok out there in a smug, conspiratorial land. But alas, the Republic is not run out of the Academy of Athens, and the electorate is less forgiving than Socrates’ students.

This curious inversion of Rahul Gandhi’s decision not to give an affidavit has been defended by his supporters as a mark of his refusal to legitimise a tainted body. Yet this is purest sophistry. If the institution is corrupted, then all the more reason for its corruption to be combatted within a legal framework to shine a light on and redress its failings. When you are crusading for yourself but refuse to ride into battle, then you are a paper knight.

This episode, which is only the latest in a long string of rhetorical follies — from Rafale to Adani, from GST to electoral bonds confirms the impression that Rahul Gandhi has perfected the art of on-the-hoof indignation; where every issue, announced with a moralistic roar as the scam of the century, promptly gets parked when public attention lapses. In all cases, the public is left with a general odour of suspicion; the institutions with their clean-up act and wrought cavils; and finally, the Congress Party with yet another look at why its president never seems to mature into a statesman. Keep in mind that political communication, at its best, combines good rhetoric with responsibility. So, while a leader can get away with speaking passionately, he had better be able to substantiate what they said with the cold precision of fact and the bravery of legal exposure. The way Rahul Gandhi is carrying on now, showing some flash without any fight to match, reveals a grave underestimation of this principle. He acts as if declaring something is proof that it exists and merits belief, and the accuser must prove the accused’s guilt.

That kind of belief is the worst enemy of republicanism. In a genuine democracy, all citizens have the right to be considered innocent until proven guilty. Leave aside the institutions of democratic governance, which form an inescapable corollary. That turns that presumption on its head, guilty until they convince one to their satisfaction of their innocence, an attitude that is anti-democratic in the extreme and decidedly demagogic. In the end, of course, there is the issue of whether Rahul Gandhi himself genuinely believes wrong has been done. As necessary as sincerity seems, it does not replace competence. You can be sincerely wrong, sincerely reckless, or just plain sincerely out of your depth in leading a nation of 1.4 billion souls. What this episode shows is that its performative proclamation, its lack of evidence, its fallback to judicial recusal and reckless reframing of institutions, is a disposition geared toward resistance as theatre rather than governance practice.

It is the cruellest irony that the very virtues that Rahul Gandhi seems to admire in himself, his moral seriousness, his refusal to be cowed by power, his self-image as champion of the voiceless, are negated by his inability to turn belief into consequence. Politics is no longer a rhetorical competition to see who can weep the most melodious lament that makes us drown in sorrow for our country, than cricket or football is about declaiming about the better side. It is practised as the demanding practice of translating conviction into programme, indignation into change and criticism into creative distillation. So far, the evidence suggests Rahul Gandhi is a bon vivant in the first, a dabbler in the second and an alien to the third. At a time of shivering anxieties, the Republic can scarce afford leaders who get their kicks from shooting off easy accusations rather than demonstrating hard facts. For all its pyrotechnic welly, Rahul Gandhi’s “Vote Chori” jeremiad has turned out to be a storm in a demitasse, loud, frothy and over before you knew it, without even the tincture of sour truth, but grumpy dregs of old grievance instead. In that, it is a perfect symbol for his political career thus far: an endless boast of magnificence which, upon closer inspection, is barely more than a breath.

Comments