In a groundbreaking archaeological discovery, evidence of a human settlement dating back 4,000 years has emerged from the historic town of Maski in Raichur District, Karnataka. The discovery, made during an extensive excavation near the Mallikarjuna Temple and Bala Anjaneya Temple hillocks, is attracting global attention, with scholars comparing it to the Harappan and Mohenjo-daro civilisations that flourished between 3300 BCE and 1300 BCE.

This significant revelation has not only placed the small town of Maski on the international archaeological map, but it has also brought it to the attention of the world. Still, it has also ignited renewed interest in Karnataka’s rich and lesser-known prehistoric past. The excavation, which began several years ago and has intensified over the past few months, has unearthed numerous artefacts, ancient structures, carvings, and symbolic motifs dating back to the Neolithic and early Iron Age periods.

Unique carvings and the state emblem were discovered

Among the key highlights of the excavation is the discovery of a stone carving of the Gandabherunda, the mythical two-headed bird that is now the official emblem of Karnataka. What makes the Maski depiction particularly unique is that it features four elephants within the design, unlike the traditional emblem, which typically depicts two. This carving is located inside the Mallikarjuna Temple, a structure believed to be over 1,400 years old, originally built during the reign of Jagadeka Malla and later renovated by King Jayasimha.

Another fascinating find is a three-faced swan motif carved into the temple stone, remarkably resembling the emblem used by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT). The emblem, which symbolises faith, education, and economy, is thought to have originated from a similar carving style that has its roots in the Vijayanagara Empire, suggesting historical continuity in cultural symbology.

A 20-member international team leads the excavation

The excavation effort is being spearheaded by a global research team of over 20 archaeologists and students, including experts from Stanford University (USA), McGill University (Canada), and Indian institutions. The project is jointly led by Prof. Andrew M. Bauer of Stanford, Peter G. Johansen of McGill, and Hemanth Kadambi from Delhi. Together, they are using modern archaeological techniques to document remnants of ancient human habitation, daily life practices, and ritual activity from the region.

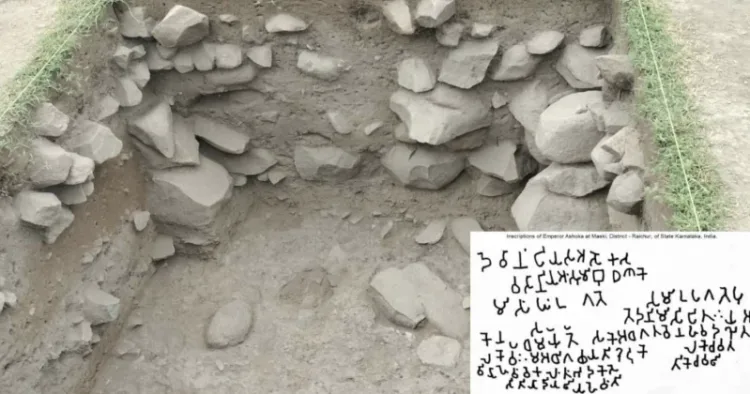

Excavations are being conducted at over 271 distinct sites around the Maski hillocks, including former granaries, iron-working spaces, gold mining zones, cremation grounds, rock shelters, and religious shrines. The research is focused not only on unearthing ancient materials but also on understanding the socio-economic life of the inhabitants who once lived here.

Traces of agriculture, pottery, and ancient homes

According to preliminary findings, the region was a flourishing settlement during the late Neolithic period, transitioning into the early Iron Age. Charred remains of food grains, terracotta pots, and charred storage jars—some still containing burnt grains—have been recovered from the excavation pits, providing direct evidence of the agricultural practices and storage methods employed by ancient people. The researchers have also identified the structural outlines of homes made from clay and stone, confirming the existence of a well-organised settlement.

The team has traced changes in social structures through burial practices, architectural evolution, and changes in diet and craft. These findings also help chart the trajectory of human evolution in southern India during the 11th to 14th centuries, offering glimpses into the daily lives of ordinary people what they ate, how they lived, and the materials they used.

A decade-long research journey

Excavations in Maski have been ongoing since 2010, with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) granting permission for extended studies. The anthropology departments at Stanford and McGill universities are collaborating on the research. What started as a localised exploration has now developed into a large-scale international research initiative, expected to continue until 2025.

The findings have not only contributed significantly to the historical understanding of southern India’s early civilisations but also sparked discussions about updating history textbooks to include Maski’s archaeological relevance alongside Harappa and Mohenjo-daro.

The ultimate aim of this long-term project is to reconstruct the socio-cultural fabric of ancient southern India by examining how ordinary people lived, worked, and evolved throughout millennia.

Comments