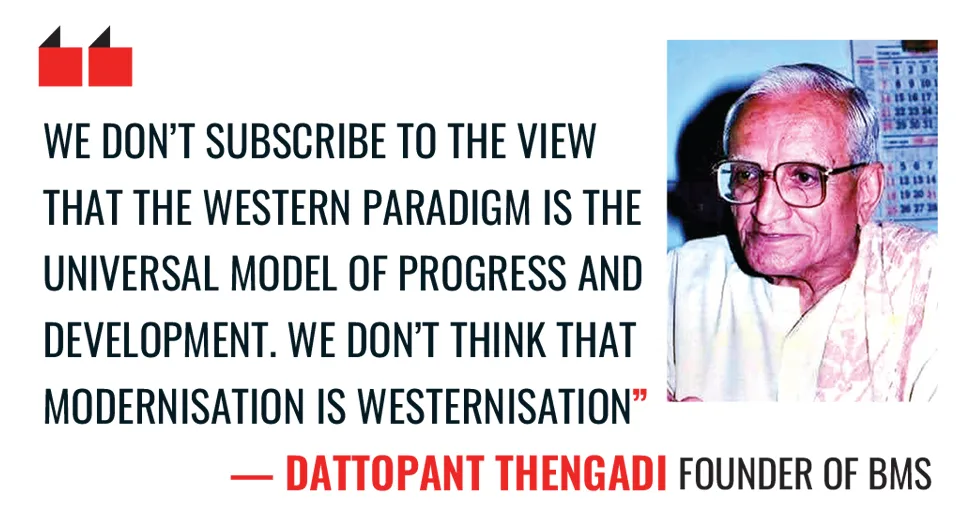

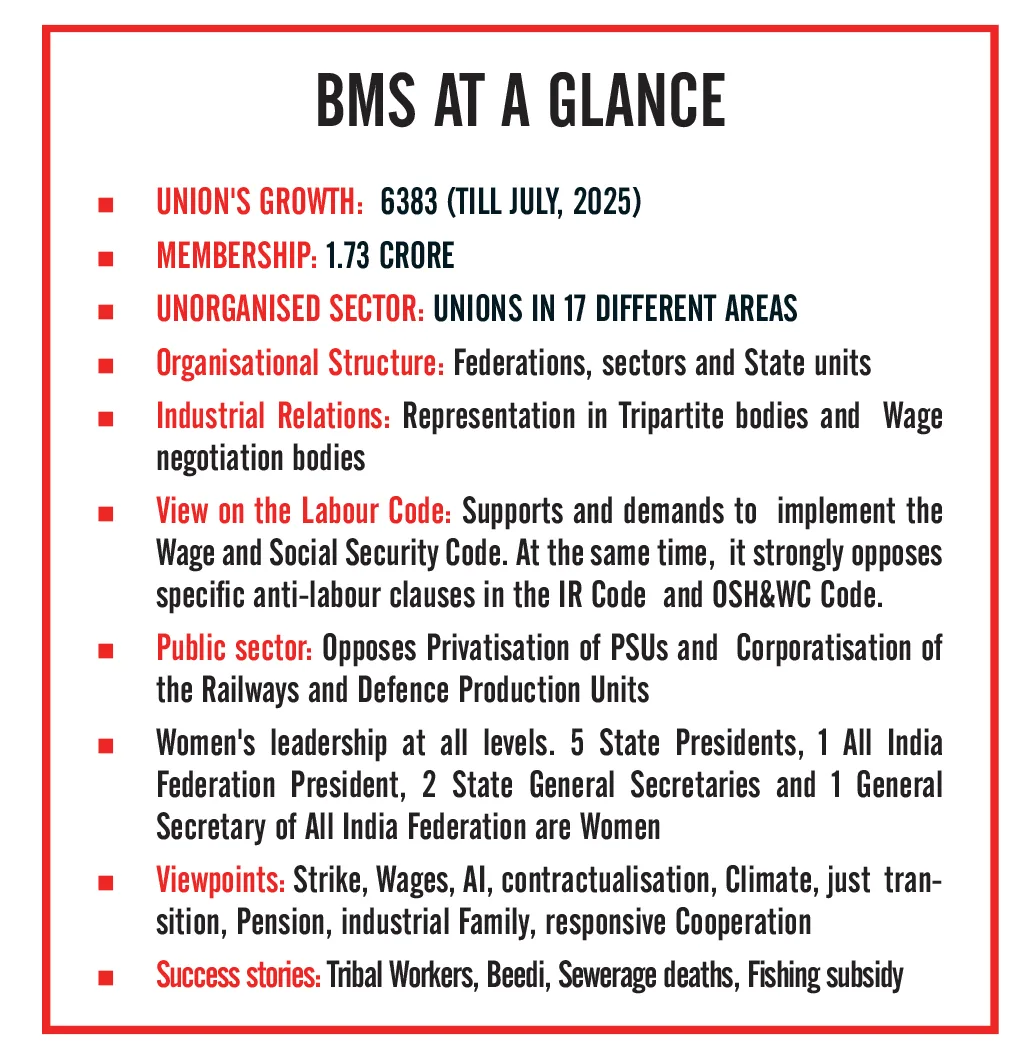

Dattopant Thengadi, the founder of Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), often remarked that BMS was a “Sangh Srishti” – a creation of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. He founded the organisation under the able guidance of Revered Guruji Golwalkar, the second Sarsanghchalak of the RSS. Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh was the last of the major central trade union organisations to be formed, after AITUC, INTUC, HMS, and others. Yet, within just 34 years, it rose to become the largest Central Trade Union in the country. Throughout its journey, BMS championed issues often ignored by other unions.

Bharat has a rich tradition of a powerful trade union movement. Much of the progress and rights enjoyed by workers today are the result of tireless struggles led by towering figures like M K Gandhi, Dr B R Ambedkar, and Dattopant Thengadi, who were also eminent leaders of the trade union movement.

National Spirit at the Core

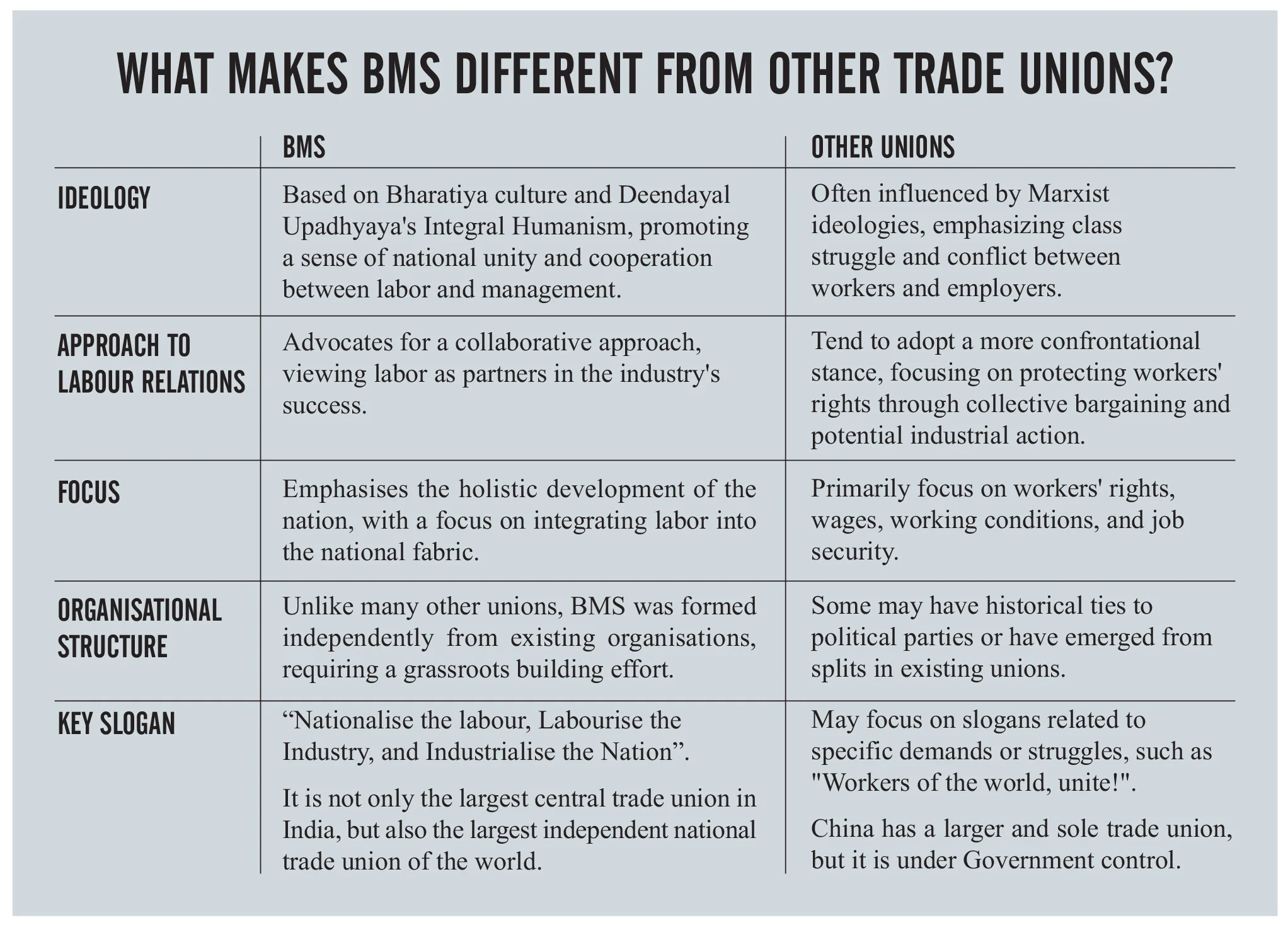

BMS has been at the forefront in ensuring decent wages and working conditions for the workers. But it always thought beyond bread and butter. It has been distinguished by its deeply patriotic character. Its rallying call in the labour sector was “Nationalise the Labour”. It firmly rejected both “political unionism” and mere “bread and butter trade unionism.” In negotiations, BMS advocated not just for the workers but considered society at large as a third and most critical partner in all industrial matters, apart from workers and employers. While striving for better wages and improved working conditions, BMS consistently emphasised that workers’ efforts must contribute meaningfully to nation-building. This balancing vision was captured in its inspiring slogan: Desh ke hit mein karenge kaam, kaam ke lenge poore daam (“We shall work in the nation’s interest, and receive full wages for our work”). In times of national crisis, BMS consistently called upon Indian labour to rise in service of the nation. During the Chinese aggression in 1962, the Indo-Pak wars of 1965 and 1971, and the liberation of Bangladesh, BMS mobilised like-minded trade unions to form the Rashtriya

Mazdoor Morcha to support the government’s war efforts. It also suspended all protests and demands during these periods.

Landmark Contributions in the Service of Labour

BMS has been at the forefront of many groundbreaking labour reforms. Wages constitute the most critical element in fulfilling the economic aspirations of the labour. BMS was the first to critically study and expose flaws in the calculation of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the basis for determining Dearness Allowance. Despite initial opposition from other unions like INTUC and HMS, who later came to endorse it, the movement gained momentum, culminating in a successful Mumbai Bandh on August 20, 1963. The government eventually appointed the Lakdawala Committee to revise CPI methodology.

BMS championed the principle that the bonus is a deferred wage, advocating the slogan “Bonus for All” – a position later adopted by all major partners in the labour sector. The First National Commission on Labour, chaired by Justice Gajendragadkar, was established in 1967. BMS made an exhaustive submission before the Commission outlining a comprehensive set of demands for the welfare of labour.

A Voice of Resistance in Times of Oppression

On July 26, 1976, Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency. In response, the Lok Sangarsh Samiti was formed, and a joint circular was issued by BMS, CITU, HMS, and HMKP. While leaders of other central trade unions were later afraid and reluctant to continue the agitation against the autocratic rule, BMS took to the streets, resulting in the arrest of more than 5,000 of its activists, with around 111 imprisoned under the oppressive MISA law. The courageous resistance and the sacrifices made by BMS during the Emergency won the confidence of workers across the country. It led to a period of growth for the organisation after the Emergency was lifted in 1977. Representing BMS for the first time, Dattopant Thengadi attended the 63rd session of the International Labour Conference of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1977 as part of the Bharatiya delegation. By 1980, BMS was declared the second-largest Central Trade Union in the country by the Congress Government, next to INTUC. Following this, BMS was officially included in every Indian trade union delegation to international conferences and forums such as the ILO. Finally, based on the 1989 verification conducted by the then Congress government, BMS was declared the largest central trade union in the country by the same Government. Consequently, in the 1990s, BMS was entrusted with the responsibility of leading Indian delegations to the ILO and other international forums.

By 1980, the Government officially recognised BMS as the second-largest central trade union, after INTUC. Following the 1989 verification conducted by the Congress government, BMS was declared the largest central trade union in the country. From the 1990s onwards, BMS began leading Indian delegations to global labour fora, including the ILO. BMS has consistently strived to foster unity among trade unions in India to safeguard workers’ interests. In 1980, leaders from various trade unions were invited to participate in the Viswakarma Jayanti celebrations, which BMS observed as Labour Day. On June 4, 1981, a National Campaign Committee comprising of eight Central Trade Unions and National Industrial Federations, including BMS, was formed to counter the government’s flawed anti-labour policies. In 1986, ten central trade unions once again united to form a common platform to address broader issues such as national unity, disarmament, and racial discrimination. BMS welcomed this initiative and played a leading role in these activities with the vision of advancing world peace and harmony.

Challenges and the Path Forward

The unorganised sector (UOS), also known as the informal sector, constitutes a massive 93 per cent of Bharat’s total workforce. This vast segment includes individuals engaged across a variety of roles from self-employed workers to daily wage labourers—without the protections or privileges offered in the formal employment landscape. A defining characteristic of this sector is that a majority of its workers belong to economically weaker and socially backward communities. These individuals often represent the most valuable yet exploited segments of our society. Deprived of basic social security measures such as pensions, medical facilities, housing, and job protection, they remain vulnerable despite their immense contribution to the economy.

BMS Categorised U.O.S. Workers

The BMS recognising the diversity and complexity of this sector, has classified the unorganised workforce into four broad categories based on the nature of their work. The rural unorganised sector includes Krishi Gramin, Vanvasi Mazdoor, Matsya Mazdoor, Beedi Mazdoor. The urban unorganised sector comprises construction workers, street vendors, domestic workers, and tailoring workers. Then there are scheme workers, such as those involved in Anganwadi, ASHA, Mid-Day Meal programmes, NHM, Bank Mitra, and Krishi Mitra. The fourth category includes migrant workers, both from sending and receiving states. A rising trend in this domain is the emergence of platform workers individuals associated with companies like Ola, Uber, Swiggy, and Zomato, as delivery agents and service providers—who also fall within the unorganised sector and need to be categorised.

Unorganised Sector’s Unorganised Workers

Moreover, even within the organised sector, there exists an unorganised workforce in the form of contract workers. These include Theka Mazdoor, casual workers, outsourced employees, and individuals hired under different contract terms such as on-roll, off-roll, fixed-term, or young professionals. This contractual model, often borrowed from Europe, and is not suitable for India.

Different Types of U.O.S.

The unorganised sector is further divided into different types based on how workers are brought under regulation. Some areas are act-based, like handloom, beedi, plantation, street vendors, and construction workers. Others are governed through executive orders, such as workers in Anganwadi, ASHA, and Midday Meal schemes under the NHM. Scheme-based employment includes professions like community-based tailoring, while emerging sectors involve plantation workers and self-employed individuals via startups.

Problems

Each segment of this sector comes with its own set of problems. For instance, handloom workers face a tough battle against changing fashion trends, lack of Government policy support, and the new generation is not interested in these works. Beedi workers have been targets of international NGO campaigns and face constant administrative neglect with no clear alternatives for livelihood. In the plantation sector, geographical isolation, poor wages, and deteriorating working conditions discourage investment and labour retention. Street vendors deal with climate shocks, administrative harassment, and musclemen while the Street Vendors Act remains largely unimplemented. Forest workersoften lacking consistent employment. Scheme workers like Anganwadi and ASHA staff are overburdened, underpaid, and still denied recognition as ‘workmen’ even after three decades, yet they punishments and record preparation work.

New Threat

A new threat is observed in institutions like the Construction Workers Welfare Board. While these boards hold vast funds meant for welfare, they’ve become a double-edged sword. Both union activists and administrative officials exploit them. This trend is visible across all types where welfare boards exist.

What is the Way Out?

To address these issues, there must be a combination of rights-based and service-based strategies. Activists working with UOS must be guided by social compassion, prioritising the grievances and hardships of workers.

As an organisation working in the economic field, BMS prioritises the economic development of both individuals and the nation. It actively promoted the ideals of swadeshi in Bharat’s economic activities. During its seventh national conference in 1984, held in Hyderabad, BMS declared a ‘War of Economic Independence Against Imperialism.’

Technology, But Not at the Cost of Jobs

The introduction of computers raised pressing questions about the impact of new technology on labour. Even today, the world grapples with the implications of Industry 4.0, artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics, and other innovations invading the employment sector. BMS firmly believes that technology and machines should assist, not replace, human workers. Given Bharat’s status as a labour-surplus country, BMS asserts that technologies should be ‘adapted’ to suit Bharatiya conditions rather than ‘adopted’ in their original form, as uncritical adoption may adversely impact employment. In line with this, the 1981 Hyderabad conference resolved to observe 1984 as ‘Anti-Computerisation Year’ in protest against labour-displacing devices. However, BMS did not object to the use of computers in complex domains such as research, defence, meteorology, oceanography and the like. It also demanded a Round Table Conference involving all partners to deliberate on the job-displacing impacts of computerisation, particularly in sectors like banking. Four decades later, the world is once again engaged in the same debate, raising similar concerns and arguments in response to the growing spread of artificial intelligence and robotics.

On the international front, BMS replaced the class-divisive Communist slogan “Workers of the World, Unite!” with its message of harmony: “Workers, Unite the World!” BMS has maintained positive relationships with global trade union movements. Notably, BMS was invited as a special guest to the pro-Communist Conference of the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) in Moscow in November 1991. At this conference, Prabhakar Ghate presented before the World, BMS’s apolitical ideals for a genuine trade union movement. When the ILO proposed incorporating a social clause in trade agreements with developing countries, BMS strongly opposed the move. The social clause, which aimed to prohibit imports from countries allegedly using child labour, would have jeopardised export prospects for nations like Bharat and Nepal. The then BMS representative, R Venugopal, mobilised many developing nations against it.

To empower women workers, BMS established its women’s wing during the 1981 conference in Kolkata. In April 1994, the Sarvapanth Samadar Manch was founded to foster religious harmony in Bharat’s diverse cultural landscape. In 1995, the “Paryavaran Manch” was launched to address environmental concerns, such as the rising levels of industrial pollution and their adverse effects. The initiative championed the Bharatiya ethos that “Mother Nature should be milked, not exploited.”

A Leader in Modern Labour Movements

On November 23, 2011, BMS held a historic rally in Delhi, attended by nearly 2 lakh workers, which was an unprecedented show of strength in recent decades. In that event, BMS declared the beginning of a sustained agitation. The show of strength inspired other trade unions, and on the very next day, their leaders came to the BMS office to plan joint actions, accepting the leadership of BMS. Two nationwide strikes followed on March 28, 2012 and February 20-21, 2013, by all the central Trade Unions together under BMS leadership. These actions had a significant impact, drawing serious attention from the government, employers, media and all those related to labour. For the first time, Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh directly intervened at the eleventh hour and appointed a group of four ministers to engage with trade unions and address their demands. During the Indian Labour Conference held in Delhi on May 17, 2013, the Prime Minister openly recognised the demands of trade unions, rekindling hope and enthusiasm among workers across the country.

The 46th Indian Labour Conference, held on July 20-21, 2015 after a gap of more than two years, marked a turning point amid turbulent labour conditions. During the conference, in a committee on ‘Labour Law Reforms’ chaired by the BMS representative, all three social partners — employers’ organisations, the 11 central trade unions, and government representatives from both the Centre and the States — unanimously agreed upon three foundational pillars for all future labour legislations: (i) the rights and welfare of workers, (ii) the sustainability of enterprises and job creation, and (iii) industrial peace.

When the four Labour Codes were in the drafting stage, a team of BMS karyakartas actively participated in the Government’s consultation process, while other Central Trade Unions belonging to opposition parties chose to boycott it. As a result of BMS’s proactive engagement, several major pro-labour reforms, particularly steps toward the universalisation of labour benefits, were successfully incorporated into the Codes. However, certain clauses still contain provisions that remain a cause of serious concern. Thus, the Code on Wages and the Code on Social Security are considered historic and revolutionary in many respects. Nevertheless, BMS remains committed to its ongoing struggle to amend the anti-worker provisions in the remaining two Codes.

Bharatiya Voice in the Global Labour Arena

BMS has also taken on a new role in global leadership. In 2016, for the first time, BMS assumed the Presidency of the BRICS Trade Union Forum. The BRICS conference held in Bharat that year received high praise from international delegates for its organisation and hospitality. In 2021, amid the pandemic, the BRICS TUF conference was once again held, this time online, under BMS’s presidency. The year 2023 was a significant milestone as Bharat hosted the G20 Summit under the Presidency of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Labour20 (L20), one of the key verticals of the summit, was chaired by BMS as Bharat’s largest central trade union. The L20 conference saw participation from representatives of 20+9 countries, making it the most widely represented L20 event to date.

During the Indo-Pak conflict in May 2025, BMS declared its unwavering support for the soldiers guarding the nation’s borders. It pledged not to engage in any strikes or agitations that could hamper production during the period of conflict. A nation cannot claim development while the majority of its working population languishes in low economic standards, poverty and vulnerability. Therefore, BMS has steadfastly promoted the philosophy of “antyodaya”—upliftment of the last worker—as an essential component of its foundational ideology, “Ekatma Manav Darshan.” The Bharatiya social order envisioned by Dattopant Thengadi was deeply rooted in this concept. Over the decades, BMS has played a vital role in transforming Bharat’s labour sector and will continue this struggle until the vision of antyodaya is fully realised. Looking back on its 70-year journey, BMS stands as a testimony to unwavering dedication and selfless service to the nation and its workforce, a legacy that ensures the fulfilment of its mission in the years to come.

Comments