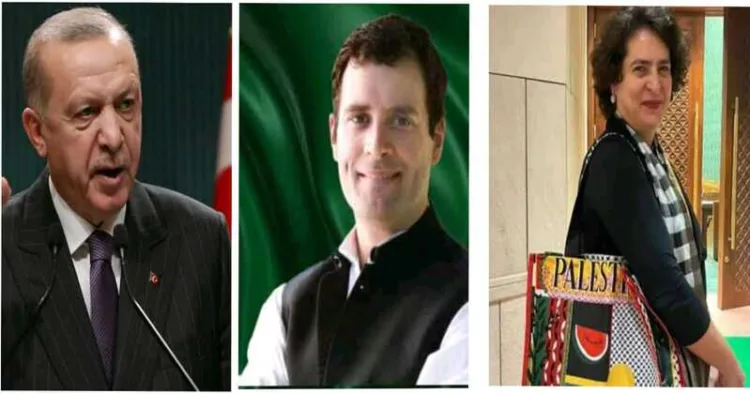

In recent years, an unusual geopolitical development has begun to unfold, one that sees the ideological and strategic convergence of two powerful political dynasties: the Nehru family of India and the Erdogan family of Turkey. Though separated by geography, culture, and religion, both families now appear to be connected through their parties’ international manoeuvring and quiet consensus on the contentious issue of Kashmir to the benefit of Pakistan.

Congress opens shop in Erdogan’s backyard

In November 2019, the Congress Party, under the influence of the Nehru dynasty, opened an overseas office in Istanbul, Turkey, via its international wing, the Indian Overseas Congress (IOC). The move was widely promoted as an initiative for fostering bilateral ties and cultural exchange. Mohammad Yusuf Khan, head of the Turkey IOC chapter, stated that the office’s purpose was to build “people-to-people connections” between India and Turkey.

Yet, the timing raised eyebrows. The Istanbul office was opened just three months after India abrogated Article 370, a move that stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status. The international backlash was loud, and Turkey, under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, emerged as one of the fiercest critics of India’s Kashmir policy. Erdogan used his UN General Assembly address to echo Pakistan’s stance and accused India of human rights violations, a position welcomed by Islamabad.

Given these developments, Congress’s decision to formalize its presence in Turkey, a country now at the forefront of anti-India lobbying on Kashmir, appears not only ill-timed but politically loaded.

From Delhi to Ankara: dynasties aligned on Kashmir

Congress leaders have cited historical ties between India and Turkey, especially the Khilafat Movement, to justify deeper engagement. The movement aimed to preserve the Ottoman Caliphate. Congress’s current posturing revives this symbolism, even as Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) pursues neo-Ottomanist ambitions.

But beyond symbolic echoes of the Khilafat era, there appears to be a contemporary ideological alignment between the Congress party and the Erdogan family, particularly on the issue of Kashmir. It was the Nehru-led Congress that granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370, a provision incorporated through a 1954 Presidential Order that bypassed Parliament. Article 370 allowed Jammu and Kashmir its own constitution, a state flag, and substantial autonomy, treating it almost like a separate country in all but name.

This decision was shaped in the backdrop of Pakistan’s invasion of Kashmir in 1947, a conflict during which Nehru’s leadership faltered. His refusal to immediately accept Maharaja Hari Singh’s offer of unconditional accession, and his insistence on installing Sheikh Abdullah as Prime Minister, delayed critical military responses. Influenced by Lord Mountbatten, Nehru hesitated to send troops until the Instrument of Accession was signed, a delay that allowed Pakistani-backed forces to advance deep into Kashmir. It widely believe that these missteps nearly cost India the region.

Fast forward to today, the Nehru legacy continues along similar lines. When Article 370 was abrogated in August 2019, Rahul Gandhi and the Congress party vehemently opposed the move. Rahul called it an “abuse of executive power” with “grave implications for national security,” and the Congress Working Committee condemned it as a violation of federalism and democratic norms. All Congress regimes have also taken a very soft approach towards Pakistan, even in the face of its continued export of terror into Indian territory, aligning with Erdoğan’s vocal support for Kashmir’s autonomy and Pakistan’s narrative.

Like the Congress, Erdogan’s AKP today projects itself as the vanguard of global Muslim solidarity. Under Erdogan’s watch, Turkey, like congress, has emerged as a vocal defender of the Kashmiri cause, using soft power, media, and educational networks to push its narrative.

The Erdogan network: soft power with hard intentions

Turkey’s outreach on Kashmir is far from benign. Many reports outlines how Turkish institutions many with Erdogan family links have become hubs for anti-India propaganda.

The International University of Sarajevo (IUS), for instance, is a major node in this network. Founded by SEDEF, a Turkish educational foundation tied to the AKP and led by Erdogan’s son, Bilal Erdogan, the university has openly hosted discussions equating Kashmir with Palestine, promoted BDS-style boycotts against India, and honored Erdogan himself with a doctorate.

Events such as the CIGA (Center for Islam and Global Affairs) seminar “Kashmir and Palestine: The Struggle for Freedom” in 2020 featured Pakistani officials and pro-Muslim Brotherhood figures advocating for global action against India. Such platforms amplify Islamabad’s narrative using Turkey as a staging ground, all under Erdogan’s watch. Congress is also supporting Palestine and Kashmir in a similar line.

Congress and the silence that speaks volumes

While we do not directly accuse the Congress of participating in this anti-India campaign, we raise troubling questions. Why would Congress, knowing Turkey’s open hostility on Kashmir, choose to open an office there? Why has the party remained silent on Erdogan’s continued support for Pakistan’s Kashmir stance?

It is important to note that Congress has neither condemned Erdogan’s UN remarks nor distanced itself from Turkey’s controversial international positioning. This silence, paired with its continued presence in Turkey, implies a tacit acceptance, if not ideological alignment.

A new brotherhood: Turkey, Pakistan, and Congress?

Turkey’s alliance with Pakistan on global platforms is no secret. Whether it’s joint statements on Kashmir, coordinated diplomatic campaigns, or educational initiatives targeting India’s image abroad, the Ankara-Islamabad axis is strategic and sustained.

By aligning itself, even indirectly, with Erdogan’s Turkey, Congress risks placing itself in the middle of this axis, potentially lending legitimacy to anti-India rhetoric abroad. The Nehru family’s refusal to speak against Turkey’s actions adds to this perception.

Moreover, several left-liberal academics, journalists, and NGOs in India, ideologically aligned with the Congress, have found common cause with Turkish institutions echoing anti-India themes. While not evidence of coordination, this ideological overlap further blurs the lines.

The unfolding relationship between the Congress party and Erdogan’s Turkey raises critical questions for Indian diplomacy and domestic politics. Is the Congress leveraging its historical roots for international outreach, or is it enabling a narrative that undermines India’s sovereignty?

What is clear is that both families, the Nehrus and the Erdogans, are engaging in parallel strategies rooted in historical legacies and contemporary ambitions. Whether this marks the emergence of a new political axis or a convergence of convenience, the implications for India’s Kashmir policy and national unity are far-reaching.

Comments