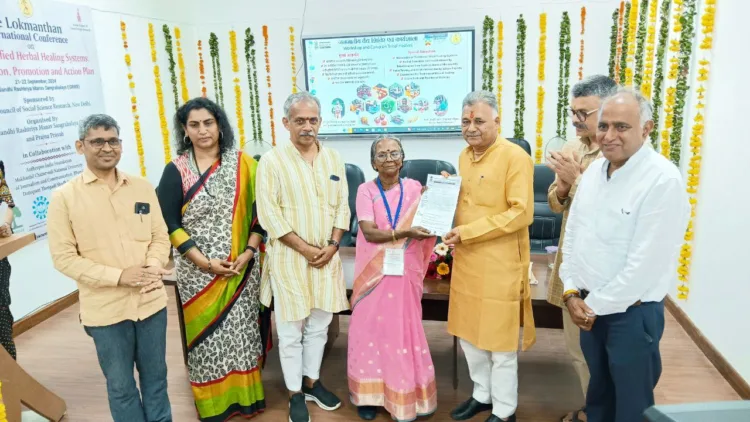

The two-day international conference on the non-codified herbal healing systems used by indigenous communities, or the Janjatiya Samuh, concluded on September 22 in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. The event ended with the presentation of a policy draft to Inder Singh Parmar, the state’s Minister of Higher Education. This draft included recommendations from healers, researchers, anthropologists, and practitioners of mixopathy (a blend of various medical systems) on how to structure the future of these traditional practices. Key points discussed in the draft were the codification of these systems, the need for separate institutions, financial support, a repository for documentation, and fair benefit-sharing agreements with indigenous communities if their knowledge is used by others.

Minister Parmar assured the participants that he would take the necessary steps to make Madhya Pradesh the first state to implement such a policy framework. He extended his full support to the research team behind the conference, promising assistance and cooperation whenever required.

During his speech at the event, Parmar emphasised the importance of recognising traditional herbal practices. He stated, “People often overlook what is right in front of them. Ayurvedic and herbal practices serve as direct evidence, passed down through generations, even if extensive research has been lost. For example, avoiding sleeping under trees at night may seem like a superstition, but it is based on traditional wisdom. The government is working to organise and validate these practices, but more effort is needed.”

He further added, “We are overly reliant on allopathy, but it cannot solve everything, as we saw during the COVID-19 crisis. Every country should develop its traditional medical systems and integrate them into healthcare structures.” Parmar assured the gathering that the Madhya Pradesh government would work with officials to create a clear roadmap for improving the system. He stressed that the state would ensure that AYUSH and traditional practices reach the grassroots level, offering support for any necessary research.

The conference began on September 21 with a grand inaugural session, which featured Shri Durga Das Uike, Union Minister of State for Tribal Affairs, as the chief guest. Co-chairing the session were prominent figures such as J Nandakumar, National Convenor of Prajna Pravah, KG Suresh, former Vice-Chancellor of Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication, and Dr Sunita Reddy, Associate Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). Other key participants included Prof. Amitabh Pande, Director of Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya (IGRMS), Bhopal, Vinod Kumar, Director of the Tribal Research Institute, Madhya Pradesh, and Mukesh Mishra, Director of the Dattopant Thengadi Institute.

The conference also brought together over 100 traditional healers who came to Bhopal to showcase their practices at the event and an accompanying mela (fair) organised by IGRMS for tribal communities from September 21 to 25. Among these healers, three had been honoured with the prestigious Padma Shri award for their contributions to society: Yanung Jamoh Lego, Shri Arjun Singh Dhruve, and Lakshmikutty Amma.

Busting Abharatiya Agenda

Shri Nandakumar spoke about the upcoming Lokmanthan 2024, which is scheduled to take place in Bhagyanagar (Hyderabad) in November. He mentioned that several pre-Lokmanthan events are being organised across Bharat, with the “Healers’ Conclave” being one of them. In his speech, Nandakumar shared the origins of Lokmanthan, which began in Bhopal in 2016, led by a group he described as Rashtrasheel, individuals for whom the nation is paramount. He said Lokmanthan serves as a counter to those with an Abharatiya mindset—those who claim Bharat is not a unified country, or a nation still in the making, or a conglomeration of smaller nations.

Nandakumar argued that the belief that non-modern, traditional healing practices are unscientific stems from an “Abharatiya” viewpoint. He said, “If you’re talking about science, what is more scientific than this? These indigenous communities, though they speak different dialects and have diverse names for their healers—Vaidyas or otherwise—are part of one Bharat. Their healing practices are unified from the Himalayas to the seas, much like the cultural unity of Bharat. Before the British arrived, how else were people being healed? What some call ‘alternative medicine’ is actually pratyaksha (visible) and yatharth (real)—it’s not just contemporary but living.”

He added that Lokmanthan is a platform for those who wish to engage in dialogue about Bharat through a Bharatiya perspective, and the Pre-Lokmanthan event aimed to address the health sector, specifically non-codified health practices.

Parameter to decide what’s scientific and what’s not

KG Suresh, during his speech, highlighted the lack of communication about herbal healers and their practices. He pointed out that modern medicine often takes a uni-dimensional approach, whereas traditional systems are multi-dimensional. “For example,” he said, “allopathy talks about ‘general medicine,’ but in our ancient practices, there is no ‘general’ category. Our uniqueness lies in the fact that different prakritis (natures) of people require different treatments. Allopathy treats symptoms, whereas our practices address the root cause.”

He raised a critical question, “Who is going to decide what is scientific and what is not? What are the parameters? Will nations with populations of six crore dictate the healthcare practices of a nation of 134 crore?” Suresh also addressed the debate over the metallic content in traditional medicines, defending the practice and urging the promotion of these healing systems. He expressed optimism about the conference’s recommendations and looked forward to their consideration by the relevant ministries.

For and by the Indigenous people

After the inaugural session, which also featured traditional dance performances by the Gond and Gudum tribes, both predominantly found in Madhya Pradesh, Dr Sunita Reddy presented the core objectives of the conference. She highlighted the significance of non-codified herbal healing, the pivotal role of herbal healers, and the challenges they face in maintaining the health of their communities. Her presentation also touched on broader issues like climate change, biodiversity conservation in relation to herbal healing, the need for advocating a policy framework for non-codified healers, and the development of an action plan to support them.

The two-day conference included seven sessions spread across both days, each dealing with various aspects of herbal healing and the contributions of indigenous healers. Researchers and presenters covered a wide range of topics, including the role of traditional healers, the wisdom they offer in treating their communities, the challenges they face in promoting herbal practices, and community models of herbal healing. Other areas of focus included the intersection of biodiversity, forestry, and herbal healing, as well as discussions on the documentation, certification, and conservation of herbal practices. Special attention was given to the need for recognition and support for these healers. Presenters hailed from countries like Thailand, Nepal, Russia, and various parts of Bharat.

Researchers emphasised the urgency of codifying these practices with government support. They warned that independent projects could lead to the misuse of knowledge, which they see as a vital part of Bharat’s rich cultural and medicinal heritage. Others argued that codification might limit the benefits to the healers themselves, particularly the tribal communities from which these practices originated.

A key point of debate arose around forest department regulations that restrict Indigenous communities from accessing forest areas, which has forced many to abandon their traditional healing practices. Some have been compelled to seek employment in other sectors, moving away from their ancestral knowledge. There was a call for the issuance of a certificate to officially recognise the healers, thereby legitimising their practices under Indian law. Researchers also demanded the creation of a dedicated repository, akin to the Quality Council of India, to support and preserve the knowledge of herbal healers. Community healing centres, or “Aushadi Kendras,” were suggested as an alternative to the current practice where healers treat patients in their homes.

Unique research in codifying healing practices

During the sessions, presenters like P.C. Dubey, Sanjay Vyas, Vinod Bhandari, Sushil Upadhyay, and A.P. Tiwari shared details of their pilot project in Madhya Pradesh. This project, in collaboration with Aurobindo College, focused on documenting herbal healing practices in five zones across 20 tribal districts of the state. Between April and September 2024, they collected data on more than 70 ethnobotanical plants used by tribal communities to treat a variety of ailments. They spoke of the challenges in building trust with tribal healers and emphasised that their documentation efforts were strictly for preservation, not commercial exploitation. The researchers also set up a dedicated testing and research centre at Aurobindo College and plan to present their findings to the Madhya Pradesh government.

The conference highlighted how tribal healing practices are deeply rooted in “Lok Swasthya Parampara” (people’s health tradition), with an intrinsic connection to biodiversity. Tribes often worship specific plants or animals as deities, with each clan having a particular species they revere. Presenters also explored the challenges of intellectual property rights and patenting, which is a complex and rigorous process requiring significant support. The discussions also touched on the influence of global forces, including economic imperialism and the role of arms and drug lords, in undermining India’s indigenous healing traditions.

There was a call to incorporate traditional healing methods into the curriculum under the National Education Policy (NEP). Ayurveda doctors also presented research on the impact of biodiversity loss on medicinal plant resources, urging the government to create dedicated forest regions for healers to protect and preserve the herbs they rely on. They warned that without such efforts, even the substitute herbs being used today could face extinction.

What do the healers say?

One of the highlights of the conference was a session with five healers, including three Padma Shri awardees and two others—Gangadhar from Madhya Pradesh and Piyush Mandal from Odisha. Gangadhar is renowned for treating pain and paralysis cases, while Piyush is famous as the first male “gynecologist” from his village, attracting patients from other states for kidney and liver-related treatments as well. During the session, Padma Shri Lego shared her experience of being dismissed as a “Jhola Chaap” (quack) by allopathic doctors, yet she continued practicing her family’s tradition. Similarly, Gangadhar, who has received multiple awards and attended conferences both in India and abroad, highlighted how countries like Thailand and Nepal have recognised traditional healers, while Bharat has been slow to do so. He acknowledged that while the AYUSH ministry has offered some support over the last decade, true recognition will come only when the government formally certifies these healers. He also pointed out that many healers encourage their children to pursue other professions, as traditional healing no longer provides a viable livelihood.

Piyush, meanwhile, shared that his ancestors never charged for their services, as they believed accepting payment would be a disrespect to their knowledge. This sentiment reflects the deep cultural and spiritual roots of India’s indigenous healing practices, which the conference aimed to preserve and promote for future generations.

By the conclusion of the conference on September 22, Dr Sunita Reddy presented a set of suggestions and recommendations, which were to be submitted to Minister Parmar. She categorised these recommendations into three sections: practitioners, research, and policy.

Policy draft and recommendations

Recommendations for Practitioners:

1. It was suggested that a unified term, such as “Local Health Specialist” or “Lok Swasthya Chikitsak,” be adopted. Practitioners should be empowered to become agents of change in their communities and beyond, advancing the herbal healing system.

2. Emphasis was placed on documenting traditional healing practices that promote self-reliance, local autonomy, and sustainable lifestyles. These efforts should foster holistic development within communities.

3. There should be efforts to create networks and platforms where local health specialists can share their experiences, collaborate, and develop joint initiatives to strengthen herbal healing practices.

4. A formal mechanism should be established to recognise and reward the contributions of local health specialists to their communities. This could include certification, awards, scholarships, and access to necessary tools and resources.

5. The dissemination of traditional knowledge should be supported through various mediums, such as community radio, educational manuals, plays, and television shows.

6. It is important to foster partnerships between local health specialists, academics, and researchers to enhance the generation and dissemination of traditional knowledge. Local health wisdom should be celebrated through festivals and cultural activities.

7. Digital documentation of traditional practices should be prioritised. A community-driven dispute resolution mechanism should also be established to ensure fairness and maintain trust.

8. Community-driven initiatives should be encouraged to fund and support practitioners, ensuring the continuity of these services. Training centres for local health specialists should be established at the village and panchayat levels, ideally within a 20-kilometer radius of every community.

Recommendations for Research and Academics:

1. Encourage interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research between academics and practitioners to develop locally appropriate governance models for traditional healing practices.

2. Develop and implement a curriculum on traditional healing systems (Lok Chikitsa) for schools, colleges, and universities to educate students about indigenous practices.

3. Support community-based research initiatives to explore traditional knowledge and build a holistic approach to health with local communities as equal partners in the knowledge-sharing process.

4. Develop transparent models for startups and funding to ensure sustainable development and support for traditional healing practices.

Policy Interventions:

1. Local health practitioners should be recognised as vital contributors to society, and their role should be legally acknowledged. A separate governing body should be established to identify, register, document, and recognise local health specialists.

2. Policies should be developed that promote social, cultural, and economic equity, rooted in local traditions and autonomy. These policies should support environmental justice and foster the preservation of cultural heritage.

3. Collaboration between government institutions, civil society, and community groups should be strengthened to promote local health specialists and their practices.

4. Community-based initiatives that promote self-reliance and local autonomy should be developed. Policies should focus on the preservation and promotion of traditional knowledge systems and cultural practices.

5. Local healers should be granted access to forest areas to collect medicinal plants. The state and central governments should provide support for the creation of dedicated healing spaces, such as “healer huts,” for practitioners to carry out their work.

These comprehensive recommendations are designed to protect, promote, and preserve the rich tradition of herbal healing while encouraging collaboration between healers, researchers, and policymakers. The Pre-Lokmanthan event in Bhopal is just the beginning of deeper discussions and consultations in this field. Healers expressed optimism about the proactive approach of researchers and the government, looking forward to long-awaited recognition. With unwavering sincerity, they continue to serve the community, safeguarding their generational knowledge and traditions, which have been passed down with care and devotion through the ages.

Comments