“The President has been pleased to award Bharat Ratna to Karpoori Thakur (posthumously),” a Rashtrapati Bhavan communique said. Prime Minister Narendra Modi posted on X that “this prestigious recognition is a testament to his enduring efforts as a champion for the marginalised and a stalwart of equality and justice”.

And with this historic announcement, political pundits started their well-known and now tiresome iteration. The Bharat Ratna to Karpoori Thakur (1924-1988) is being dubbed as Bharatiya Janata Party’s counter to the caste survey in Bihar and of the Congress demand that a nationwide caste census be undertaken. The pundits missed the larger picture again. BJP has already gained a decisive advantage in the politics on caste survey by defeating Congress in Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh. And it wasn’t long back, right? This monumental Bharat Ratna to the champion for the marginalised should be seen as a stepping stone in a long journey towards equality and justice. After all, Karpoori Thakur had poetically said, ‘Adhikar chaho to ladna seekho, pag pag par adna seekho, jena hai to marna seekho.’

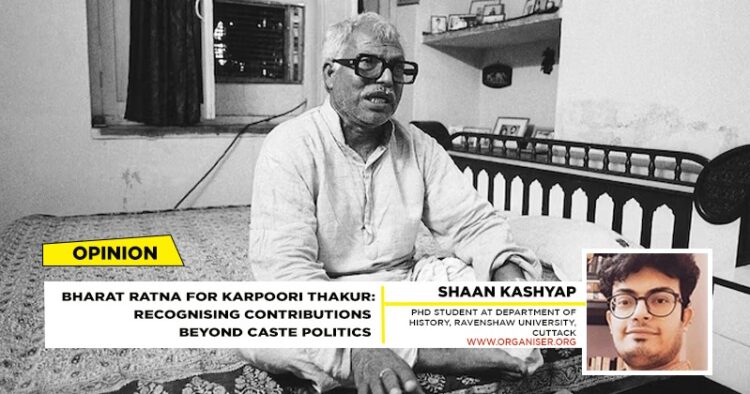

A People’s Leader

Son of a marginal farmer from the Nai (barber) community, and later named Jannayak, or People’s Leader, Karpoori Thakur was a freedom fighter incarcerated during the Quit India movement in 1942. He entered the Bihar Assembly as a Socialist Party member in 1952 and rose to become Deputy Chief Minister and the first non-Congress Chief socialist Chief Minister of Bihar. This socialist icon served twice as Chief Minister of Bihar — first between December 1970 and June 1971 as part of the Bharatiya Kranti Dal and later between December 1977 and April 1979 from the Janata Party. He remained an MLA till his death in 1988, except when he lost an Assembly election in 1984, amid the sympathy wave for Congress after Indira Gandhi’s assassination.

Karpoori Thakur is known for many of his decisions — removing English as a compulsory subject for the matriculation examinations, prohibition of alcohol, preferential treatment for unemployed engineers in Government contracts, through which around 8,000 of them got jobs, and a layered reservation system. During Karpoori Thakur’s CM-ship in 1977, the Mungeri Lal Commission submitted its report recommending that backward classes be reclassified as extremely backward classes (including weaker sections of Muslims) and backward classes. The report was implemented in 1978. Thus paved the way for 26per cent reservation for them in the Government services in Bihar in November 1978. No wonder the politics and its pundits are adamant today to reduce Karpoori Thakur’s legacy only to the factor of caste. But was he only about caste dynamics?

A Kaleidoscopic Life

It is obvious and natural for the BJP to think of Karpoori Thakur as someone who belongs to its politics in the larger sense of the term. After all, three central thrusts of Karpoori Thakur’s politics align with the BJP. Firstly, Karpoori ji was one of the mainstays of Anti-Congressism. This phenomenon and process had its origin in the effort to unite the Opposition against Congress by Ram Manohar Lohia and Deendayal Upadhyaya a month prior to Jawaharlal Nehru’s death in April 1964 when they had a pact in Kanpur. PM Narendra Modi’s call for ‘Congress Mukt Bharat’ is also an extension of the same Anti-Congressims that was initialised in the 1960s and was later championed by the likes of Karpoori Thakur.

In the 1977 Bihar Legislative Assembly election, the ruling Indian National Congress suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Janata Party. Janata Party was a recent amalgam of disparate groups, including the Indian National Congress (Organisation), Charan Singh’s Bharatiya Lok Dal (BLD), Socialists and Hindu Nationalists of Jana Sangh. Karpoori Thakur became the Chief Minister but couldn’t complete his term due to internal tensions of the Janata Party, which also met the same fate on the national stage. While the Janata Party was brought down by Socialist leaders like Raj Narain and Madhu Limaye on the RSS membership of erstwhile Jan Sangh members (who thereafter founded the BJP), socialist icons like George Fernandes and Sharad Yadav, in the spirit of the Lohia-Deendayal pact, supported alliance with the BJP.

Moving on, Karpoori Thakur was a votary of Hindi and vernacular languages. Karpoori Thakur was the Education Minister of Bihar from March 5, 1967, to January 28, 1968, and in this capacity, he removed English as the compulsory subject for the matriculation curriculum. While it is alleged that the Bihari students suffered due to the resulting low standards of English-medium education in the State, Karpoori Thakur had a futuristic vision of the power and efficiency of vernaculars. It was a move aimed at ensuring that the educationally backward did not suffer and could pursue higher education in their own language. No wonder the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 under the Modi Government has made it a priority to promote the use of vernacular languages in education, even for technical and professional degrees.

Next, Karpoori Thakur championed a political culture of corruption-free and clean public and private life. A popular anecdote about him is that when he first became an MLA in 1952, he was selected for an official delegation to Austria. He did not own a coat and had to borrow a torn one from a friend. When Josip Tito, the president of Yugoslavia, noticed the torn coat, he gifted a new one. When Karpoori Thakur died in 1988, after three decades in public life, his home was little more than a hut. Karpoori Thakur represented a clan of politicians who were dedicated to social change alone and not to self-interest.

An Icon for New India

Karpoori Thakur’s political life was about chasing and realising a dream. It was a dream to champion social justice in vernacular languages and rallying for a corruption-free society as an individual. A society where English could not be allowed to become a barrier between the marginalised and elite, a society where a political culture cannot be allowed to become a hegemon. A society where a pro-poor approach and dedication to the cause of the downtrodden is given primacy over any other business. Most of these traits seem to have become the central thrust in New India.

It is unfortunate that the political disciples and alleged successors of Karpoori Thakur missed his grand vision for change. They have often sided with the same exploits of the Congress System which Karpoori Thakur kept fighting against. It seems Karpoori Thakur’s call of ‘Adhikar chaho to ladna seekho’ is taking a new shape in Narendra Modi’s call of ‘Panch Pran’ in Amrit Kaal. A Bharat Ratna for Karpoori Thakur on his birth centenary is a welcome step that is certainly beyond caste politics.

Comments