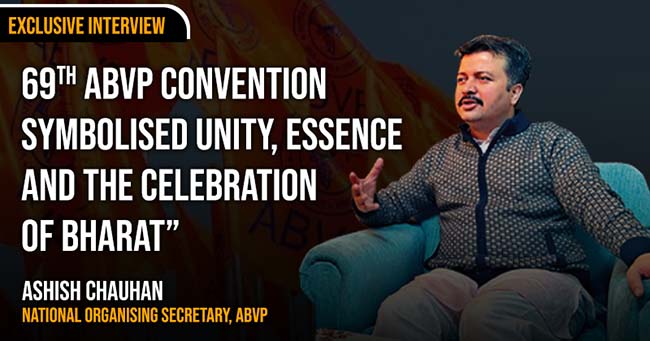

The 69th national conference of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), marking the 75th foundation year of the nationalist students’ organisation, reached its conclusion on December 10 at the Indraprastha Nagar, a specially built, eco-friendly tent-city in the national capital. Students, karyakartas and delegates representing all parts of the country gathered together to participate in this historic event. Following the success of the conference, Ashish Chauhan, National Organising Secretary of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), shared insights into the mega event and beyond with Organiser Special Correspondent Nishant Kumar Azad and Sub-Editor Yatharth Sikka. During the conversation, he spoke about the organisation’s journey, the challenges it faces, and the strategies employed to expand its reach among the youth on and off the campuses. Excerpts:

ABVP has completed its 75 years of journey. How do you see this?

ABVP completing its 75 years is a significant journey, passing through multiple generations of karyakartas. In the context of an organisation with students as karyakartas, whose involvement typically spans three to five years, and given that membership beginning from class 9th around age of 14-15, and continuing through various educational pursuits like degrees, masters, and even Ph.D. programmes, makes the work very challenging. In the early years, ABVP was active in universities mainly in Northern parts of Bharat, such as BHU, Allahabad University, and Delhi University. Initially, there was no pan-Bharat structure. The early understanding of generational shifts was limited, but in 1960s, with the presidency of Acharya Giriraj Kishore, a new phase of legacy-building commenced. His extensive travels across Bharat helped connect people and establish a broader network.

The subsequent contributions of leaders like Yashwant Rao Kelkar ji and Madandas ji, and Bal Apte ji from Mumbai in the late ’50s and the matured phase in the ’60s shaped ABVP further. The shift of the presidency from one karyakarta to another marked the progression of generations within ABVP. By the early decades, Delhi was the major centre, followed by the involvement of karyakartas from Mumbai and other regions.

The conference served as a platform to inspire students by presenting a comprehensive understanding of historical figures, encouraging them to draw inspiration, build ideas, and take pride in their heritage. The idea of Vishwaguru Bharat does not reside only in the past; it was nurtured in the phase of resistance and need to be reinvented for the future. VIdyarthi Parishad is preparing youth for the same

In ABVP, where karyakartas generally stay for around three years on college campuses, almost a decade can be considered a generation. Over the years, there have been approximately six-seven generations, with a practical understanding of seniors and juniors within the organisation. Large conferences, held approximately every ten years, become milestones for participants, with significant memories associated with these events. Mega-movements, triggered by social, educational, or cultural issues, have also played a crucial role in shaping ABVP’s journey. Events like the Kashmir Andolan in the 1990s, agitation for educational demands in 2002, the Kishanganj (Bihar) agitation in 2008, and the Kerala Chalo Maharally movement in 2017 have left indelible imprints on the memories of karyakartas. These movements, often mobilising tens of thousands of students, gets itched in the memories of the Karyakartas.

What are the key achievements of this conference? Why this kind of mobilisation in national capital?

Our Swarna Jayati (50 years of ABVP) adhivesan took place in Mumbai with over 12,000 participating delegates. Before this, in 1985 the lar biggest gest convention took place in Delhi , commemorating the Year of Youth and touching upon Vidyarthi Parishad. When contemplating the organisation of a significant event marking the 75 years of ABVP, it naturally gravitates towards cities like Delhi, Mumbai or Bengaluru—a megacity with the requisite capacity to host such a momentous programme.

I can’t say what would be the immediate impact of the adhivesan but the celebration of Viraat ABVP will endure in the memory of our Karyakartas. The event symbolised unity, the essence of Bharat, and the celebration of the Bharat. Even the naming of the adhivesan city as ‘Indraprastha’ underscores the continuous journey of Bharat from the times of Mahabharata to the present. It’s a narrative that encompasses highlighting historical nuances often overlooked, such as the British took power of Delhi from the Marathas, not the Mughals.

Exhibitions at adhivesan emphasised these historical insights for the benefit of our youth. The impact on Karyakartas and youngsters is expected to be profound, offering a true understanding of Bharat’s history. Beyond this, the celebration of youth, their involvement, and the meticulous planning required for such a grand event are essential lessons. Demonstrating that a student organisation, guided and mentored by educators, can successfully execute an independent, large-scale event sets a precedent. This event serves as a model for creating a movement with sustained understanding and a long-term vision for its members and youth—an essential aspect of ABVP as an educational family. For other organisations, the people associated with the organisation are workers but our people are Karyakartas not ‘workers’. Ultimately, the adhivesan has provided valuable insights into crafting a movement that endures and fosters a lasting impact on the minds of youth involved.

Vishwaguru Bharat was the theme of this conference. How do you see the role of youth in achieving this status?

The conference featured the theme of Vishwaguru Bharat alongside Swavalambi Bharat. The conference days were divided into three categories, with Vishwaguru Bharat standing out as the overarching theme. This grand narrative was emphasised by the choice of the conference city – Indraprastha.

The celebration echoed Shivaji Maharaj’s vision of self-governance by the people rooted in the soil, rejecting foreign powers and invaders. The exhibition highlighted the enduring vision and civilisation of this ancient land, reflecting the ethos of Hindavi Swarajya and Shivaji Maharaj’s governance principles.

The exhibition specifically focused on Shivaji Maharaj’s Yatra and the principles of Hindavi Swaraja, offering insights into his governance. Additionally, the conference aimed to celebrate contemporary India, leading in the 21st century with the ongoing Amrit kaal. Vishwaguru Bharat was depicted not only in the historical context but also in the future, inspiring the youth through exhibitions showcasing ISRO’s achievements and technological advancements.

ABVP strongly opposes the commercialisation of education and has actively fought against detrimental practices associated with it. Our commitment is to resist the negative impacts of commercialisation and work towards enhancing the overall educational experience for students

The statues of historical figures like Maharaja Suraj Mal and Maharaja Mahir Bhuj, commemorate their gallant fights against Mughal tyranny. The conference also marked the 500th year of Rani Durgavati and the 2550th Nirvana of Mahaveer Swami, with students symbolically bringing soil from their birthplaces. Notably, the towns created for conferences were named after iconic figures like Rani Gaidinlu, Rani Lakshmi Bai, Rajmata Ahila Bhai Holkar, and Guru Nanak Dev Ji etc., fostering a rich memory for students.

In essence, the conference served as a platform to inspire students by presenting a comprehensive understanding of historical figures, encouraging them to draw inspiration, build ideas, and take pride in their heritage. The idea of Vishwaguru Bharat does not reside only in the past; it was nurtured in the phase of resistance and need to be reinvented for the future. VIdyarthi Parishad is preparing youth for the same.

There are many student organisations in the country like NSUI, SFI, AISA etc. What makes ABVP different from other student organisations?

There are several points to consider, with the fundamental one being that we are constructed differently. Our foundation is rooted in the ethos of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Unlike other organisations, we were not formed by a political party seeking additional votes, resulting in the creation of women’s wings, youth wings, or student wings.

We originated from grassroots level, recognising that students desired genuine leadership. At the dawn of India’s Independence, while Jawaharlal Nehru disbanded the All India Students Congress for protesting against his Government, there was a fertile ground for a movement. Students in universities needed leadership, as the struggle was no longer for Independence but for charting a distinct path forward. At that juncture, ABVP found an open space to express itself, and our journey began with the vision of the Sangh philosophy at its core.

Another significant point is that we are an independent organisation, not affiliated to any political party. This independence constitutes our second major distinction. The third noteworthy aspect is our independence, not just in terms of political affiliation but also in decision-making. This independence stems from the involvement of individuals from the teaching community and educational fraternity, forming an educational family capable of discussing and deliberating on education in a holistic manner.

Unlike organisations influenced by political considerations, we don’t approach issues from a narrow student perspective, such as advocating for lower passing marks. Instead, we adopt a perspective that is beneficial for education field. This approach creates a well-coordinated 360-degree outlook within the organisation.

One critical observation is that the national presidents of many student organisations, with whom we interact on campuses, are affiliated with political parties. They get elected to Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha, Vidhan Sabhas, and their decision-making is directly influenced by the political party. The leaders and in-charges of these organisations are party members, restricting their autonomy and collaborative approach. While ABVP presidents come from the teaching fraternity.

In conclusion, anyone aiming to establish an organisation in different fields should contemplate its holistic purpose. ABVP does that in the field of education.

ABVP was in agitations, opposition to commercialisation & privatisation of education. Has it changed

its course now?

Our perspective on privatisation in education in India remains consistent. Historically, education was not solely State-owned; it was often privately owned, with the understanding that it served the interests of society. In ancient times, the responsibility for education rested on society itself rather than solely on the Government. Society took charge of educating the next generation, as power structures had their own preferences, priorities, and sometimes sought to sustain their kingdoms. Drawing upon historical instances, such as Chanakya’s debates with Ghanananda and other kings, we recognise that privatisation, in principle, is not inherently wrong. We do not condemn privatisation; instead, we celebrate the participation of private entities, organisations, and trusts in education. These entities have contributed to society for centuries, viewing their role as a form of service (seva). However, we acknowledge that recent developments have seen companies with backgrounds in running commercial ventures, entering the education sector purely as a business. This shift has led to disruptions in education, transforming it into a commodity for sale in the market—a service one must pay for.

ABVP strongly opposes the commercialisation of education and has actively fought against detrimental practices associated with it. This includes opposing high fees, unscrupulous practices by institutions, imposing financial penalties on students, and levying fees related to attendance. We advocate for improved facilities during admissions, transparency in examination processes, and a fair and efficient release of examination results. Our commitment is to resist the negative impacts of commercialisation and work towards enhancing the overall educational experience for students.

There is a general perception that ABVP is limited to Hindi belt only. Could you shed some light on ABVP footprints in other parts of the country?

When I began my work on the national-level, I recall a presentation by the then organising secretary during a session of organisational assessment at the National Executive Council meeting. At that time, approximately half of ABVP’s membership came from two states: Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, which was Andhra-Telangana combined before 2014.

It was fascinating to observe how these two States consistently contributed 50 per cent of ABVP’s membership. These States, particularly the South-Central zone referred to as Dakshin Madhya Kshetra, continue to be the powerhouse of ABVP. Over time, as our engagement and activities expanded, we witnessed growth in other regions as well, such as Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. Gujarat, for instance, saw a significant increase in membership from 40,000-50,000 to 2,67,000.

Political pressure and violence tactics restrict our Karyakartas from working freely in certain campuses, especially in States like Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. Despite these challenges, ABVP remains committed to these regions, actively increasing its strength and organising various programmes and activities. The organisation is resolute in its dedication to expanding its presence

Now, ABVP’s work has extended to all areas and territories. Despite facing challenges, especially in Bengal where violence and attacks on our Karyakartas occur regularly, we are continuously organising and striving to overcome these obstacles. If the current situation improves, our membership is expected to surge in Bengal, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. ABVP aims to reach new milestones, having already surpassed 50 lakh members. The plan is to target the next 50 lakh members from these areas, particularly in the eastern belt. However, the challenges include political pressure and violence tactics that restrict our Karyakartas from working freely in certain campuses, especially in States like Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala.

Despite these challenges, ABVP remains committed to these regions, actively increasing its strength and organising various programmes and activities. The organisation is resolute in its dedication to expanding its presence and achieving the goal of one crore memberships per year.

There is a growing influence of ‘Wokeism’ culture and the left-liberal narratives on the campuses, leading to disconnect or pushing anti-Bharat narratives in the country and abroad. Is there any strategy to counter this?

ABVP firmly believes that our grandmothers and mothers in families are our biggest supporters, and ‘Wokeism’ will not make any progress as long as our mothers and grandmothers remain committed to the welfare of their own families. The value system, particularly in Bharat, is deeply rooted in the family structure, and this is our strength. Reflecting on why Wokeism has reached a nonsensical level in certain elite campuses in India and the American academia, it’s observed that it is often marked by nuclear family orientations and extreme individualism. In contrast, in common Indian households, even in urban areas, where facilities allow, grandparents typically stay with the family. This presence ensures communication across generations. As long as we have grandparents in families and maintain thorough communication on cultural understanding and values, Wokeism is less likely to gain traction. This approach is particularly effective in states with a reasonable rural population, where cultural ties and communication across generations are integral to the societal fabric. ABVP aims to leverage these cultural foundations to counter the influence of Wokeism and Left-liberal ideologies in educational institutions.

What challenges do you foresee in front of ABVP in the coming years?

From my perspective, the primary challenge lies in our expansion in numbers and still maintaining personal touch while communicating with our karyakartas. The inherent limitation of giving time to a large number of individuals is the only challenge I foresee. If we can overcome this challenge and expand ourselves with a personal touch, ABVP as an organisation will continue to grow with its principles and inspire youth to contribute to the journey of Vishwaguru Bharat.

Comments